AI Is Breaking the University Monopoly on Science

As experiments become programmable and automated, the execution of science is concentrating in the hands of a small cluster of frontier AI and hyperscale cloud corporations. When research depends on their compute, their robotics, and their power contracts, control over discovery concentrates accordingly. That makes science a defence infrastructure question, and Britain is structurally unprepared for the coming change.

For most of modern history, universities controlled the practical execution of science. They held the laboratories, the instruments, the trained labour, and the institutional procedures that made experimentation possible at scale. If you wanted to run advanced experiments, you needed a campus.

That dominance is now rapidly eroding. Not because universities are failing, but because the scientific method is being industrialised. AI systems can design experiments, robotic systems can execute them, sensors can log results automatically, and software can select the next iteration. What once moved at the speed of graduate labour now moves at the speed of capital.

This is not a cultural shift. It is an infrastructure shift. When experimentation becomes programmable, science stops being something universities exclusively host and becomes something infrastructure runs.

From graduate labour to capital intensity

The traditional British research model is labour driven. PhD students and postdoctoral researchers carry experimental work. Grant funding supports people. Output is validated through institutions and publication. The system rewards excellence and prestige.

Automation changes the constraint. When experiments can run continuously through robotic systems integrated with AI optimisation, the bottleneck is no longer supervision capacity. It is capital depth. It is compute. It is instrument fleets. It is uptime.

Universities optimise for labour intensive research. Industrial labs optimise for capital intensive research. That difference compounds. In domains where throughput, optimisation, and rapid iteration dominate, the gap becomes decisive.

The shift is no longer theoretical. Google DeepMind’s GNoME system identified 2.2 million new crystal structures using automated computational pipelines, a scale of materials discovery far beyond what any individual academic laboratory could attempt. That is what industrialised iteration looks like.

Britain is not absent from this transition. The Hartree Centre in Daresbury provides advanced computing and AI support for industry and research, and UK biofoundry initiatives have invested in automation platforms for synthetic biology. But these facilities operate at a scale that remains modest compared with the hyperscale GPU clusters and capital depth of major US cloud providers. They demonstrate capability. They do not yet demonstrate infrastructure sovereignty.

The monopoly weakens as execution migrates away from campus

In several domains, industrial laboratories already run faster iteration cycles than universities: high throughput screening, materials optimisation, protein engineering, semiconductor testing, and AI model validation. The pattern is consistent. When iteration can be automated, it migrates toward capital rich environments.

Universities remain strong in theory, early stage exploration, and long horizon inquiry. But routine optimisation and scale based experimentation increasingly move to infrastructure backed execution platforms. The university does not disappear. Its exclusive hold over execution diminishes.

Validation shifts too. Historically, peer review and journal prestige were the legitimacy engine. Automated execution produces a different validation model: machine logged reproducibility, standardised workflows, continuous audit trails, and repeatable pipelines. If industrial labs demonstrate cleaner replication and faster validation, the funding and regulatory ecosystem follows the infrastructure, not the crest on the building.

Science is now defence infrastructure

This is no longer just about universities. When experimentation becomes programmable, automated, and compute intensive, it stops being an academic process and becomes strategic infrastructure.

Modern defence capability increasingly depends on AI training, advanced materials discovery, rapid prototyping, semiconductor optimisation, cyber physical modelling, and biodefence simulation. Each is compute hungry and increasingly automated. If you cannot execute advanced research independently, you cannot modernise defence independently.

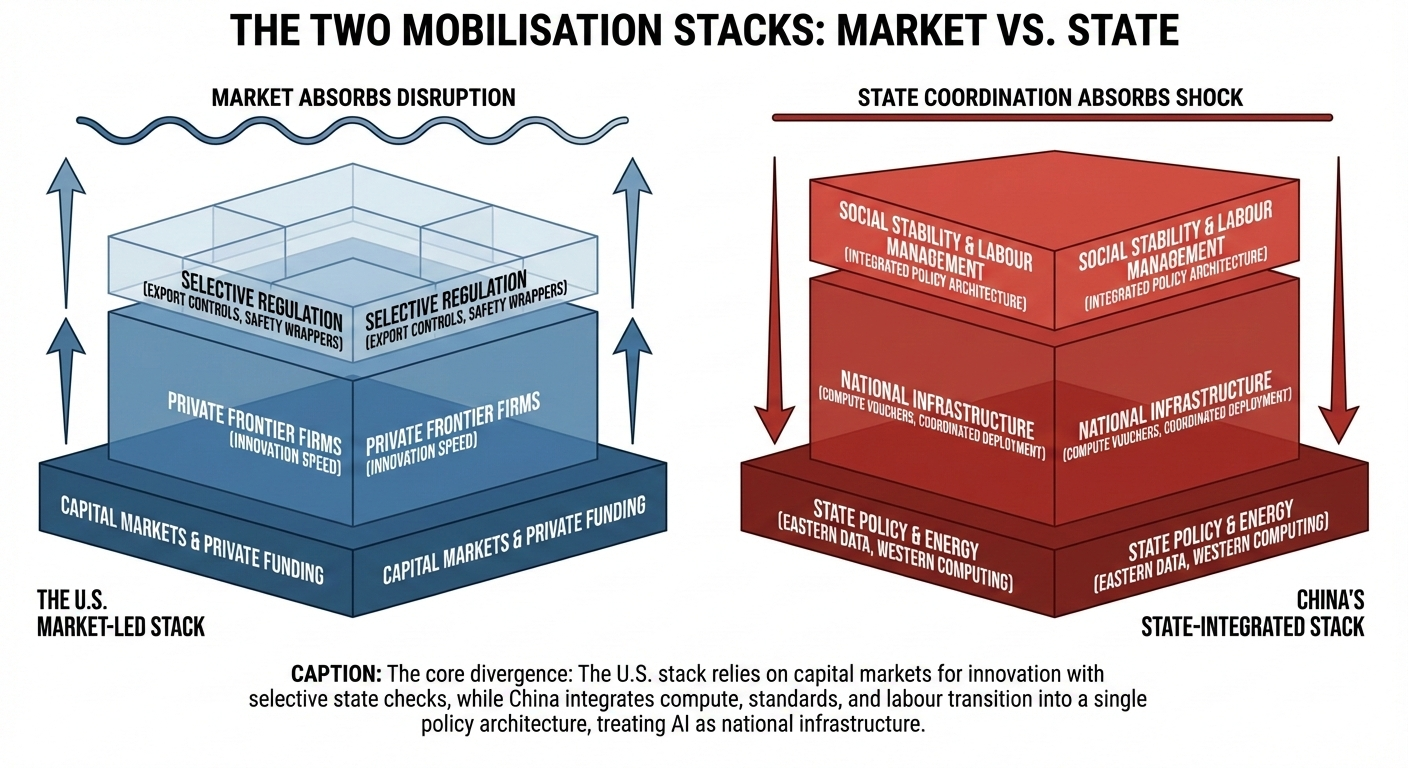

The United States treats advanced chips and AI compute as export controlled strategic technologies. China integrates AI and biotech into state industrial doctrine. Both behave as if the execution layer is national capability. Britain largely rents that layer.

Recent debate around national compute capacity and data centre planning delays has exposed how limited Britain’s independent scale remains. The UK AI Safety Institute may lead on evaluation and standards, but it does not command sovereign hyperscale infrastructure. Capability without compute ownership is advisory, not decisive.

If British defence innovation runs on foreign owned hyperscale platforms and foreign fabricated chips, then sovereignty is conditional. Conditional sovereignty is managed access.

Britain faces a choice: fiscal orthodoxy or technological sovereignty

Britain cannot assume prestige substitutes for infrastructure. For years, Westminster has prioritised fiscal restraint, debt optics, and incremental industrial policy. That approach was defensible when science was labour intensive and universities dominated execution. It is less defensible when science becomes capital intensive and infrastructure bound.

The transition forces a choice. Either Britain continues to fund people over machines, treats semiconductor strategy as niche support rather than sovereign buildout, rents compute from foreign hyperscalers, and tolerates energy pricing that deters data centre scale, remaining dependent on allied infrastructure. Or it commits sovereign scale capital to compute and automation, treats chips, energy, robotics, and data custody as national capability layers, and aligns defence, industrial, and research policy into one doctrine.

Those paths are incompatible at scale. Sovereignty requires infrastructure. Infrastructure requires capital. Capital requires political choice.

Universities will still generate ideas and train talent. But the state that controls execution speed controls deployment speed. If Britain does not own enough of the execution layer, it risks becoming a junior technological partner in the AI era: not powerless, but dependent.

The university’s near monopoly over experimental execution is ending. What replaces it will not be governed by prestige. It will be governed by infrastructure. Westminster must decide whether Britain intends to own that infrastructure, or rent it.

References

- U.S. CHIPS and Science Act fact sheet — NIST

- UK National Semiconductor Strategy (gov.uk)

- UK gross domestic R&D expenditure statistics — ONS

- DeepMind GNoME project and materials discovery results — DeepMind

- UK AI Safety Institute launch (gov.uk)

- Financial Times on compute capacity and AI infrastructure

- UK National AI Strategy — gov.uk

- How automated labs are reshaping biomedical research — Science

- Nature: Reproducibility crisis in science

- BBC: How AI is powering materials discovery

- UK energy prices and industrial competitiveness (gov.uk)

- UK Ministry of Defence research strategy

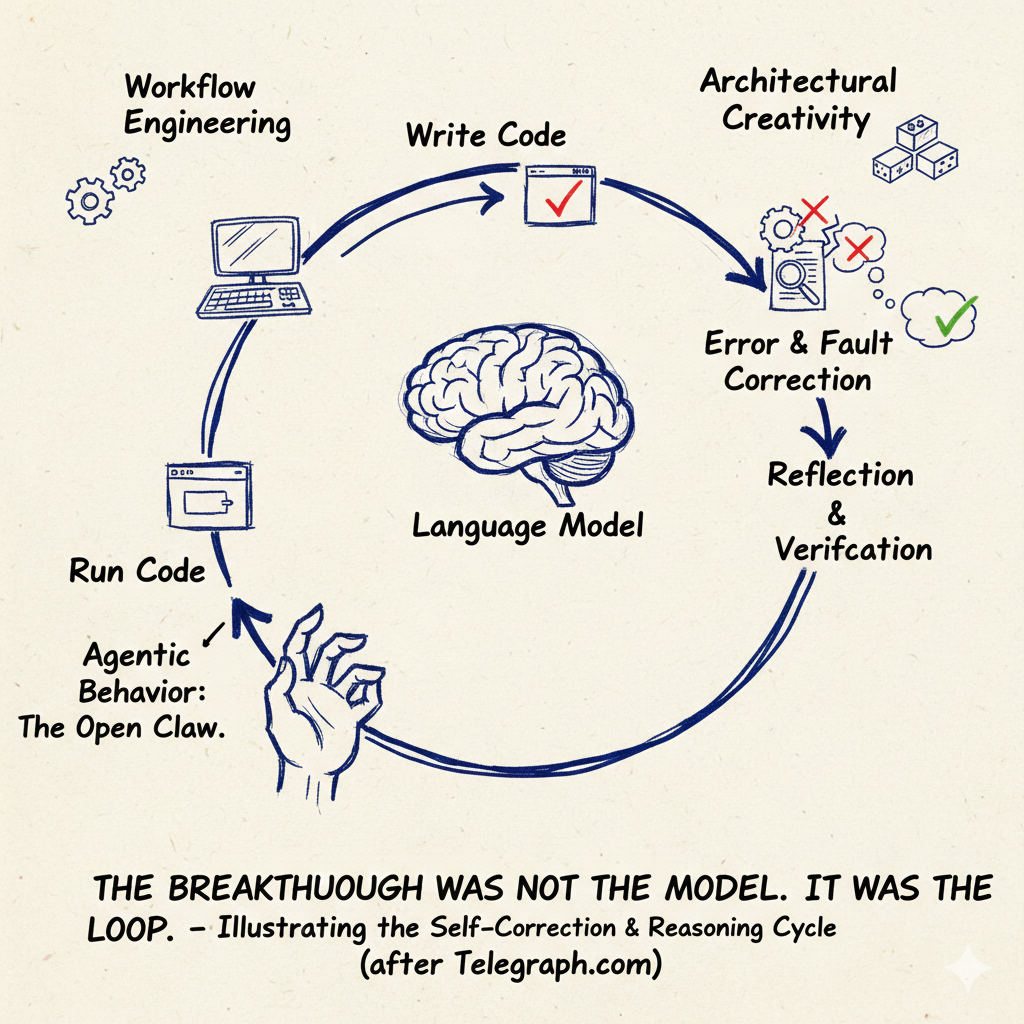

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

-

AI Is Reordering the Labour Market Faster Than Education Can Adapt

Why the supply side education model is failing under task automation, and what an adaptive, demand led model would need to look like. -

Britain at the Crossroads: AI and Resilience in UK Workplaces

A UK focused blueprint for skills, apprenticeships, and institutional reform so the gains from AI do not bypass most workers. -

Why White Working Class Boys Are the Great Underachievers in English Schools

A hard look at attainment gaps in England, what did and did not work in reform cycles, and why the system still leaves a cohort behind. -

AI Is Raising Productivity. That Is Not the Same Thing as Raising Prosperity

Why Britain can see capability gains without broad living standard gains, and how institutions and capture determine outcomes. -

AI Productivity Gains and Britain's Economy

The second step in the argument: productivity is not the same as distribution, and Britain is structurally bad at turning efficiency into pay. -

AI Is Making Cognition Cheap Faster Than Institutions Can Cope

A systems view of why liability, regulation, and organisational design lag when machine cognition collapses in marginal cost.