Britain’s New Migration Model: Fewer Brains, More Bills

The official figure: billions cut from the tax base

The first hard number comes from the Home Office itself. In July, an impact assessment for the new work and care visa rules put the direct cost to the public finances somewhere between two point two and ten point eight billion pounds over five years, with a central estimate of five point four billion. That is the state, in writing, accepting that its own visa changes make the Exchequer worse off.

The mechanics are simple. Tightening the skilled worker route to graduate level jobs, closing the low paid care route, and raising thresholds and charges means around two hundred and fourteen thousand fewer people are expected to settle in the United Kingdom between twenty twenty five and twenty thirty. Fewer people means fewer visa fees. More importantly, it means several billion pounds less in income tax and national insurance from people who would have been of working age, already trained, already ready to work.

Even after the Home Office subtracts the cost of extra GP appointments and school places that those people might have used, it still concludes that the Treasury loses. That is the number ministers never mention when they stand in front of a podium and claim victory on migration.

At the same time, the Office for National Statistics shows that net migration has already dropped from around nine hundred and forty four thousand at its peak in the year to March twenty twenty three to about two hundred and four thousand in the year to June twenty twenty five. Immigration is just under nine hundred thousand a year, emigration around seven hundred thousand. The headline has moved. The question is how.

The official assessment of the July work visa changes accepts three points in black and white:

• The reforms are expected to reduce net migration by roughly two hundred and fourteen thousand people over five years.

• The Exchequer loses between two point two and ten point eight billion pounds as a result, even after counting public service use.

• Most of that loss is foregone income tax and national insurance from people who would have come here to work.

It is unusual for the state to admit that a flagship policy cuts its own revenues. It has done so here.

Students: chopping away a rare healthy revenue stream

The second pillar being kicked out from under the system is international students. On the surface, the changes look technical. Higher visa charges for sponsors, tougher language requirements, narrower graduate routes, and a ban on most dependants of students on taught courses. A separate Home Office assessment puts the monetised cost of these changes at around one point two billion pounds over five years, mainly from lost tuition income.

Set against the real numbers in higher education, that figure is cosmetic. International students now provide roughly twelve billion pounds a year in fee income, close to a quarter of all university income. They cross subsidise domestic teaching, research and the fixed costs of running an institution.

That pillar is already cracking. After a post pandemic surge, the total number of overseas students has slipped from about seven hundred and sixty thousand in twenty twenty two to twenty twenty three to roughly seven hundred and thirty thousand in twenty twenty three to twenty twenty four. New international entrants, the real pipeline, fell by nearly seven per cent in one year. Sector modelling suggests that even a drop of around sixty thousand students strips about one point one to one point five billion pounds a year from university fee income.

Universities UK and the regulator now warn of a multi billion funding gap over this Parliament. A growing share of providers expect to run deficits. Some are already cutting courses, freezing hiring and considering mergers.

Chinese students are the single largest group. They still come in large numbers, but the line has flattened and begun to bend down. Applications for twenty twenty four entry from China have fallen sharply. Other destinations are competing hard, and Chinese families have more options at home and across Asia than they did a decade ago. The United Kingdom has moved from being an obvious default choice to just one option in a crowded field.

• International fee income is now around twelve billion pounds per year.

• Total overseas student numbers have slipped from roughly seven hundred and sixty thousand to about seven hundred and thirty thousand.

• New entrant numbers are down by nearly seven per cent in a single year.

• Sector estimates suggest that losing around sixty thousand students removes at least one point one to one point five billion pounds in fees each year.

• Policy direction is towards higher charges, fewer dependants and shorter post study rights.

You can call this migration control. You can also call it a slow austerity programme for universities, delivered through the Home Office rather than the Treasury.

Cost of living and the end of Britain as a magnet for skills

Twenty years ago, the trade off for a skilled migrant was clear. London and the wider South East were expensive, but the salaries were high, the public services reasonably strong, and the career ladder steep. That trade off has deteriorated.

International comparisons now place the United Kingdom well down the league for attracting overseas talent. Britain has slipped in global talent rankings on quality of life, political stability and public services. London is routinely ranked among the most expensive cities in the world for foreign employees. Housing costs sit far above the average for comparable economies. Commuting and childcare swallow additional chunks of income.

For a highly trained engineer from India or Nigeria, or a data scientist from Central Europe, the calculation has changed. The nominal salary in Britain might still look impressive on paper. Once rent, transport, food and declining public services are taken into account, the net gain is much smaller. When that is combined with high visa fees, an expensive health surcharge and a hostile political climate, the attraction dulls.

Other countries have seen the gap and acted. Canada, Australia, parts of continental Europe and the Gulf states now advertise packages that combine high pay, lower living costs, faster routes to residence and a sense that their economies are in investment mode, not managed decline.

• London sits near the top of global cost of living rankings for workers.

• Housing costs run far above those in similar economies, especially for renters.

• Britain scores lower on quality of life and public service measures than it once did.

• Visa and health surcharge costs for a skilled worker with a family can run into many thousands of pounds.

• Competing destinations offer better net incomes and clearer paths to settlement.

Migrants with serious skills now have many choices. The old assumption that Britain will always be first choice is no longer supported by the evidence.

The brain drain: Britain trains people, then waves them goodbye

While the inflow of productive people is being restricted and made less attractive, the outflow of British citizens has quietly increased. Recent releases from the national statistics office show that around six hundred and sixty nine thousand people left the country in the year to December twenty twenty four, with a growing share of them British. In the year to June twenty twenty five, the United Kingdom recorded a clear net outflow of its own citizens, with well over one hundred thousand more British nationals leaving than arriving, and roughly three quarters of those leavers under the age of thirty five.

These are not tourists or retirees. They are working age people, often with degrees, often with professional training paid for by the British system.

In specific sectors the pattern is stark. Nursing organisations report that British trained nurses are looking to Australia, New Zealand and the United States, where pay is significantly higher and housing and staffing conditions are better. International staff in the NHS tell colleagues not to come to the United Kingdom at all, but to aim directly for those destinations. Recruitment surveys in science, engineering and technology report a steady stream of staff leaving for overseas roles.

Teachers and creative workers are following similar paths, moving into schools and media markets in China, South East Asia and the Gulf where salaries, housing support and professional esteem are higher. British curriculum schools and English language teaching have become an export industry. Behind the glossy brochures sits a blunt fact. Britain trains people up, then they use that training somewhere else.

• Emigration has risen, and there is now a clear net outflow of British citizens.

• The majority of those leaving are under thirty five, in their most productive years.

• Nursing, science, technology and teaching all report significant movement abroad.

• Destination countries offer higher real wages, better housing access and clearer career paths.

• Britain pays the education and training bill, and other states collect the resulting tax.

In balance sheet terms this is a transfer from British taxpayers to foreign Treasuries, recorded as personal choice and left out of domestic policy.

Who and what still come in: low wage labour and rentier capital

If Britain were closing itself off in every direction, the picture would at least be symmetrical. It is not. On the labour side, the government has hit formal routes into health and care hardest. Visas for carers and overseas nurses have collapsed by something in the range of eighty to ninety per cent after the low paid care route was closed and requirements were tightened. The need for care has not collapsed. It has been pushed back onto families, onto agency staff and into grey or informal labour markets where workers have less protection and the Exchequer often sees less tax.

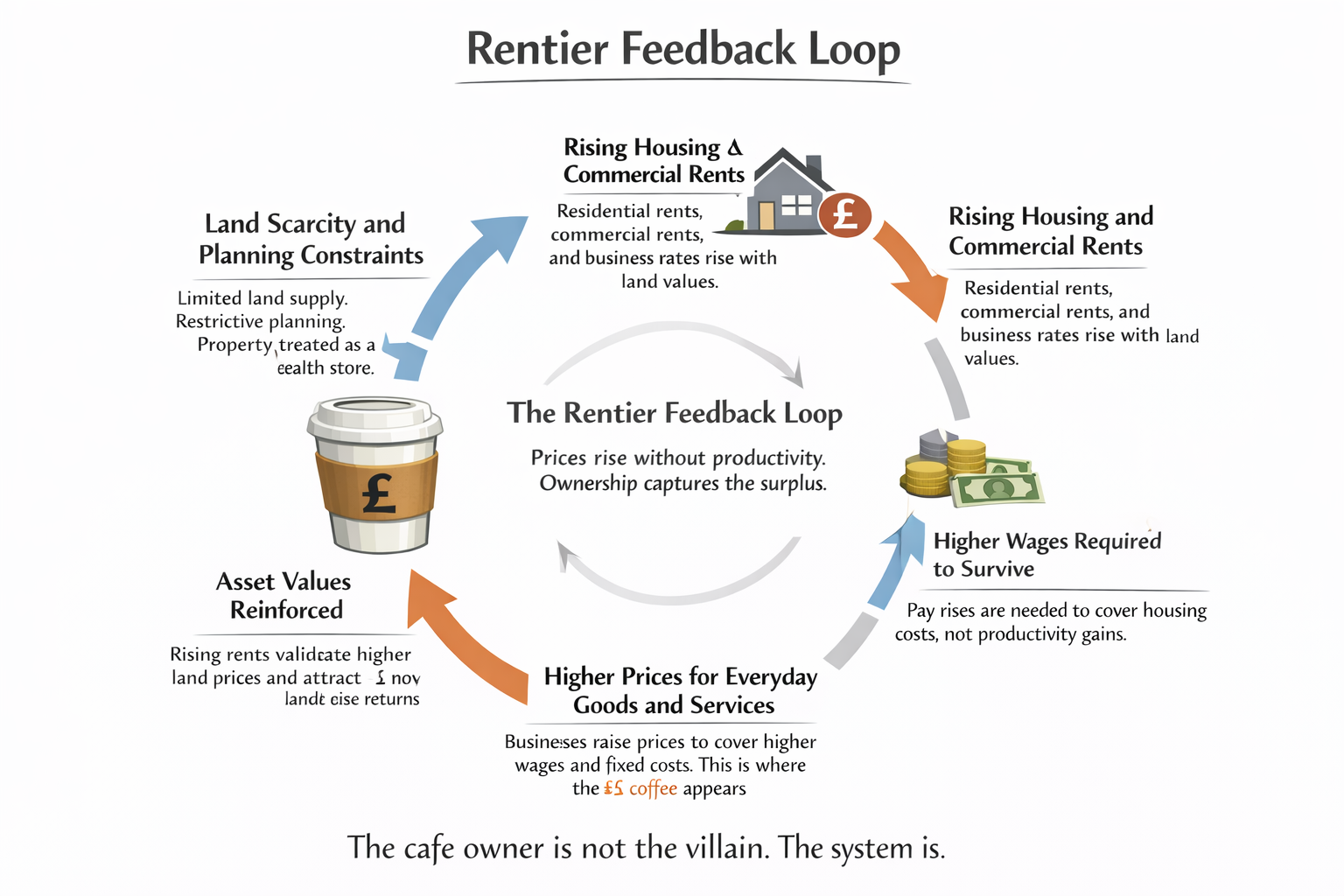

On the capital side, the door remains wide open. Over two decades, London in particular has been marketed as a safe place to store wealth. Not to build factories, not to fund new industries, but to store wealth. Investigations into property ownership patterns in parts of the capital have found large shares of new build flats owned by anonymous companies, trusts and overseas buyers with no apparent intention of living in them. The United Kingdom now has a register of overseas entities that own land, but it arrived late and leaves wide loopholes.

The effect is simple. Scarce housing is bid up by people with access to global capital. Domestic wages do not keep pace. The state then congratulates itself on tightening visas for nurses and students as if that had anything to do with local rents.

Tourism completes the picture. In a normal year, visitor spending and hospitality contribute a sizeable share of output. Central London increasingly resembles an open air museum and shopping mall where foreign visitors file past heritage sites and luxury brands, while the people who clean the rooms and serve the drinks go home to ever smaller spaces further out.

• Property in prime and inner London is heavily owned through overseas companies and high net worth buyers.

• Housing supply is constrained, the planning system is slow, and social housing stock is limited.

• High end hospitality and retail are geared to foreign visitors and wealthy residents.

• Tourism is a valuable export, but it is not a substitute for an industrial and technological base.

A micro state can live off tourism and wealthy residents. A country of more than sixty million people, with deep regional poverty and an ageing population, cannot.

The central warning

When you strip away the speeches and look only at the numbers, the pattern is clear. The government is cutting net migration by closing the routes that produce a fiscal surplus and future capacity. Work visas for skilled staff, student visas for people who pay high fees and arrive in their prime working years. Its own impact assessments admit that this will cost billions in lost tax and visa income and that the benefits for social cohesion are negligible.

At the same time, Britain is losing parts of its own trained workforce to better run systems abroad. Young professionals, nurses, engineers, teachers and creatives, educated at domestic expense, are leaving in rising numbers. The state does not even record this as a policy problem.

The gaps that remain are not being filled by a serious domestic training plan. They are being patched with low paid labour at the bottom and capital inflows at the top that inflate asset prices without building anything new. Housing becomes more expensive, not more plentiful. Universities become more fragile, not more secure. Public services lose staff faster than they can recruit.

This is not an argument about whether migration is good or bad in the abstract. It is an argument about which migration a serious country chooses. A medium sized, indebted, ageing state that wants to stay relevant should compete ruthlessly for the people who teach, heal, design and invent, and it should treat anonymous capital and speculative property flows with suspicion.

Britain is moving in the opposite direction. It is pushing away the students and workers who pay for the system, exporting the young people it has trained, and selling roofs and residence to money that expects nothing more than a safe place to sit.

That is the central warning. You can call this border control if you like. What it really controls is the slow hollowing out of the tax base, the skills base and the productive economy. A country that keeps walking down that road does not wake up one day and find itself strong. It wakes up and finds it has become a backdrop.

- Britain Is Spending the Interest on Russia’s Frozen Money. Some call it theft – How the decision to spend the interest on seized Russian reserves turns the City into a political weapon and undermines confidence in British custodianship.

- When Britain Turns Trust into a Weapon, It Cuts Its Own Throat – Why weaponising courts, regulators and markets for short term geopolitical gain slowly destroys their value.

- Europe’s Empty Promises: Why Russia Sets the Price of Peace in Ukraine – An examination of how European security guarantees outran military and industrial reality.

References

| Source | Relevance |

|---|---|

| UK Home Office, Impact Assessment on Skilled Worker and Health and Care Visa Reforms (July 2025) | Provides the estimate that tightening work and care visas will reduce net migration by about 214,000 and cost between £2.2bn and £10.8bn over five years in lost visa fees and tax revenue. |

| UK Home Office, Impact Assessment on Student and Graduate Route Reforms (2025) | Estimates an additional £1.2bn monetised cost over five years from changes to student routes, mainly through reduced international tuition fee income. |

| Office for National Statistics, Long term International Migration Estimates (2023–2025) | Shows net migration peaking around 944,000 in the year to March 2023 and falling to roughly 204,000 by the year to June 2025, with immigration under 900,000 and emigration around 700,000. |

| House of Commons Library, International Students in UK Higher Education (2024) | Documents that overseas student numbers reached about 760,000 in 2022–23 then fell to around 732,000 in 2023–24, with new entrants down nearly seven per cent and international fees at roughly £12bn a year. |

| Universities UK and HEPI analyses on international recruitment (2024–2025) | Model the impact of a fall of about 60,000 overseas students as a loss of £1.1–£1.5bn a year in fee income and warn of a multi billion funding gap and rising deficits across the sector. |

| Mercer Cost of Living Survey and global talent competitiveness reports (2023–2024) | Rank London among the most expensive cities worldwide for internationally mobile staff and record a deterioration in the United Kingdom’s attractiveness for skilled migrants on quality of life indices. |

| ONS Emigration and Nationality Breakdown Statistics (2024–2025) | Show rising emigration, a net outflow of British citizens of more than 100,000 in the year to June 2025, and a heavy concentration of leavers in the under thirty five age group. |

| Health Foundation and Royal College of Nursing reports on pay and mobility | Demonstrate significant pay gaps between the NHS and comparable roles in Australia, New Zealand and the United States and record rising numbers of nurses considering or taking roles abroad. |

| Migration Observatory and independent studies on London property ownership | Detail the extent of overseas company and high net worth ownership of prime London property, the late creation of the overseas entities register, and the impact on local affordability. |

| VisitBritain and tourism satellite accounts | Quantify the contribution of tourism and hospitality to UK GDP and employment and show the concentration of visitor spending in central London. |