Robotaxis are no longer a science fiction curiosity. In the United States, Waymo now delivers more than a million paid rides each month. In China, Baidu’s Apollo Go runs fully driverless cabs across more than twenty cities and is already claiming unit profits in Wuhan. This is what artificial intelligence looks like when it leaves the datacentre and starts to rewrite urban transport and labour markets.

In 1995 a research team from Carnegie Mellon University crossed the United States with a car that largely steered itself. Three thousand miles, Pittsburgh to San Diego, with a human sitting behind the wheel and a prototype vision system doing most of the work. That “No Hands Across America” experiment was treated as a clever stunt. Thirty years later, its descendants are taking paying passengers to work.

The public story still centres on American brands. Waymo, owned by Alphabet, runs paid robotaxi services in Phoenix, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Austin and is preparing for launches in Atlanta, Miami, Washington and Dallas. The company now reports more than two hundred and fifty thousand paid trips each week and over a million rides per month, with ten million paid rides in total and a fleet heading towards three thousand five hundred vehicles.

Tesla has finally moved from promises to a small commercial pilot, offering rides in Austin and the San Francisco Bay Area with human monitors still in the front seat. Zoox, owned by Amazon, has built a cabin shaped shuttle with no steering wheel at all and is tooling up a factory in California that could produce ten thousand such vehicles a year. General Motors’ Cruise, which once looked like the second American champion, is still trying to rebuild trust after regulators halted its service in 2023 following a serious collision and a botched response to investigators.

Global robotaxi scoreboard, late 2025

Waymo (United States) – More than 250,000 paid trips each week across four core cities, over ten million paid rides in total, and more than one million trips a month in California alone.

Baidu Apollo Go (China) – Around 250,000 fully driverless orders each week, more than seventeen million cumulative rides, operating in about twenty two cities in China and the Gulf.

WeRide, Pony and others – Chinese operators already exporting services to Abu Dhabi and preparing launches in Dubai, while smaller United States and European pilots remain at early scale.

Waymo proves the concept, China industrialises it

In public debate, America still presents itself as the home of autonomous driving. The on the ground reality is more balanced. The most aggressive deployment of fully driverless taxis is now Chinese. Apollo Go, the robotaxi arm of Baidu, runs services in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, Shenzhen and Hong Kong, as well as in Dubai and Abu Dhabi. Chinese and Gulf media report more than one thousand four hundred million fully driverless kilometres, roughly two hundred and forty million autonomous kilometres in total, and weekly orders above two hundred and fifty thousand, all without a safety driver in the front seat.

Chinese state and city governments have treated robotaxis as an industrial policy instrument, not a mere gadget. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has approved national level autonomous driving demonstration zones, with tens of thousands of kilometres of mapped test roads and many thousands of special test number plates. Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Wuhan all publish annual test reports that treat autonomous vehicles as a measurable infrastructure project rather than a public relations campaign.

Wuhan has become the key case study. City authorities there describe Apollo Go as a “city level” application rather than a district trial. Robotaxis run twenty four hours a day and are advertised as part of the tourist experience, linking new light rail and air rail links with museums and riverfront attractions. Local press reports say Baidu is targeting full operational profitability in Wuhan by 2025 and intends to use that template to scale across the country.

Alongside Baidu sit at least two other serious Chinese contenders. WeRide has built robotaxi and robotbus services in several provinces and has now signed with Uber and local partners to supply the first fully driverless ride hailing fleet in Abu Dhabi. Pony.ai, backed by Toyota and others, has permits in multiple Chinese cities and is working on a Dubai launch. All of them lean heavily on domestic chipmakers and on Nvidia’s platforms for simulation and in vehicle computing.

China’s robotaxi numbers

Chinese official and industry reports now talk about:

- Over twenty cities with some form of commercial robotaxi service, led by Baidu’s Apollo Go.

- More than one hundred million kilometres of autonomous driving without major accidents claimed by Baidu.

- Weekly Apollo Go order volumes above two hundred and fifty thousand, all with no safety driver on board.

- Cumulative robotaxi rides for Apollo Go alone above seventeen million, with global coverage stretching from Chinese megacities to Gulf hubs.

The economics: from prototype to public transport

The pitch from all sides is simple. Human labour is the biggest cost in ride hailing. If software and sensors can replace the driver, robotaxis should eventually undercut both Uber style platforms and private car ownership. The difficult part is getting from here to there without burning the balance sheet.

Consultants at Frost and Sullivan, in a detailed study of the Chinese robotaxi market, estimate that early pilot services in 2019 cost around twenty three yuan per kilometre to run. By 2023, with better vehicles, cheaper sensors and more efficient operations, that figure had fallen to around four and a half yuan, with projections of around two yuan by the middle of the decade and close to one yuan by 2030 if operators can keep vehicles busy and extend lifetimes.

Baidu has redesigned its own vehicles around this cost curve. Its latest generation robotaxi, sometimes referred to as the RT6 or Robocar Yichi 06, is a stripped down electric shuttle with no steering wheel, five lidars and a cabin built purely for ride hailing. Chinese and international trade press put the build cost at just under two hundred and five thousand yuan, substantially less than many European family cars and below the price Tesla has floated for its proposed robotaxi specific model.

Chinese suppliers have also dragged down the cost of sensors that once made every self driving prototype an exotic one off. Where early laser based lidars cost tens of thousands of dollars each, domestic producers now sell automotive grade units for around one thousand dollars or less. That matters for Western firms as much as Chinese ones. Companies like Waymo still fit multiple lidars, radars and more than a dozen cameras to each vehicle, but the unit cost of that hardware is no longer as crippling as it was five years ago.

What one kilometre of robotaxi really costs

Traditional ride hailing: American and European estimates suggest that human drivers account for half to two thirds of the cost of a typical urban trip.

Early robotaxis: Chinese cost studies put first generation robotaxi operations at more than twenty yuan per kilometre in 2019, far above private cars or ride hailing.

The next phase: If Chinese forecast curves are right, high utilisation and cheap hardware could take mature robotaxi services towards one yuan per kilometre by around 2030, below both private car ownership and conventional cabs.

For now, those unit costs are still aspirational. Independent analysts at Boston Consulting Group put current robotaxi operating costs at seven to nine dollars per mile in the United States, compared with two to three dollars for ride hailing and roughly one dollar for private cars. Chinese equities prospectuses and white papers point to similar gaps, although Baidu now claims that its Wuhan operations are at or near break even on a per vehicle basis.

Two things are doing the heavy lifting. The first is utilisation. A robotaxi can operate around the clock if there are enough riders and enough chargers. The second is vehicle life. When a car runs several hundred thousand kilometres over five years, the upfront cost is spread over a very large base. The entire game is to push down capital and maintenance costs while keeping the vehicle in motion.

Safety, trust and the politics of risk

The crucial question for regulators and the public is not just what a robotaxi costs, but how it behaves when things go wrong. Waymo has been aggressive in publishing safety data, including joint work with Swiss Re, the global insurer. Looking at tens of millions of miles of service, it claims around eighty to ninety percent fewer property damage and bodily injury claims than a comparable human baseline, and a very sharp fall in crash rates as volume has grown.

Baidu has taken a similar line for Apollo Go. In recent Chinese coverage it has claimed that its sixth generation robotaxi, combined with a dedicated autonomous driving foundation model, delivers a safety performance more than ten times better than human drivers. Company figures state that the average fully driverless vehicle now travels more than ten million kilometres between airbag deployments and that there have been no major injury incidents across the fleet.

Those are company numbers, not independent audits, and they sit alongside more uncomfortable stories. In China, taxi associations in cities such as Wuhan have publicly complained that robotaxis are eating into their income and have demanded limits on fleet size. In the United States, the Cruise incident in San Francisco, and the subsequent discovery that the company had not given regulators full footage, has become a textbook case of how not to handle a crisis. Every operator now understands that one badly managed crash can freeze an entire sector.

Policy frameworks diverge sharply. In the United States, the Department of Transportation is moving towards federal rules, but individual states still control most of the day to day permissions and can pull licences after a single high profile incident. China, by contrast, has built the technology into its Five Year planning system. Demonstration zones, insurance products and data rules are all being treated as parts of a single national industrial project rather than as separate experiments.

Platforms, ecosystems and the Nvidia problem

Once the technology works and regulators are broadly satisfied, the question becomes who captures the value. Here the picture looks less like a car market and more like a smartphone and cloud market rolled into one. At the top sit a handful of operators, such as Waymo and Baidu, who own both the software stack and a large fleet. Around them cluster traditional carmakers, ride hailing platforms and a growing number of chip and cloud vendors.

Uber has given up trying to build its own self driving system and is now positioning itself as a booking layer for whoever wins the technical race. In parts of Phoenix it already offers Waymo rides inside the Uber app. In the Gulf, it has signed with WeRide and other Chinese suppliers. In Europe, it is working with Nvidia and carmakers such as Stellantis, Mercedes Benz and Lucid on a long term plan to field tens of thousands of robotaxis from 2027 onwards.

Baidu is preparing its own international play. The Apollo Go unit has agreed a partnership with Lyft to bring Baidu backed robotaxis to Britain and Germany by around 2026, accessible through the Lyft app but running on Chinese software. Baidu has also teamed up with PostBus in Switzerland and with partners in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, turning what began as a domestic industrial experiment into a plan for global expansion.

The quiet constant across almost all of these efforts is Nvidia. The company sells data centre systems that train the driving models, simulation tools that generate synthetic kilometres, and in vehicle computers that sit behind the sensors. Tesla has already deployed tens of thousands of Nvidia H series GPUs for its self driving training. Chinese operators have announced new robotaxi platforms built around Nvidia powered hardware. General Motors, Mercedes and others have signed broad partnerships to use Nvidia technology not just in robotaxis but in factories and conventional cars as well.

The new arms dealer of mobility

Robotaxi operators compete in cities. Nvidia quietly sells them the compute to do so. Its automotive and autonomous driving division is now one of the fastest growing parts of the company, with customers on both sides of the United States China divide. In this race the chips and simulation engines are the shovels, and Nvidia is selling them to almost everyone who is digging.

What this means for Britain and the wider system

For Britain and much of Europe, robotaxis are still mostly a briefing slide rather than a lived reality. A few small pilots run in controlled zones. Regulations are debated. Insurance questions are parked in working groups. Meanwhile one American and several Chinese operators are solving the practical problems in real traffic, on real schedules, with real passengers and very large data sets.

The deeper shift is that autonomous vehicles are making artificial intelligence visible again. For years the story has focused on chatbots and image generators, systems that sit behind screens and can be written off as digital toys. Robotaxis turn models and training runs into something concrete: a car that arrives on time, or does not, and a city where labour in the transport sector is either redeployed or made redundant.

In that sense, the true contest is no longer about who has the most impressive demonstration in a Californian suburb. It is about who turns autonomous driving into reliable, cheap, normal infrastructure. On current evidence, America still sets many of the global narratives. China is quietly building the bus routes and the factories.

When the dust settles, there may be two dominant software stacks for city transport, one American and one Chinese, both wrapped around vehicles made in many different plants and managed through platforms like Uber. Britain will then have a narrow choice: treat this as a strategic infrastructure question and decide whose system is allowed to run on its streets, or continue to pretend that robotaxis are someone else’s experiment. The cars, and the data they generate, will not wait.

References

| Source | Relevance |

|---|---|

| Waymo company blog and press statements (2023–2025) | Trip volumes, safety statistics versus human drivers, city rollout and fleet expansion in the United States. |

| Reuters, AP, Business Insider, Forbes coverage of Waymo, Zoox and Cruise | Independent confirmation of paid weekly ride counts, factory plans, and the shutdown of Cruise services after the San Francisco incident. |

| Baidu Apollo Go site and Chinese state media (Xinhua, Hubei Daily, Wuhan government) | Chinese robotaxi city coverage, weekly fully driverless orders, cumulative rides, distance driven and Wuhan commercialisation plans. |

| Chinese language reports on Apollo Go safety claims | Statements that the sixth generation Baidu robotaxi, combined with an autonomous driving foundation model, is claimed to be many times safer than human drivers. |

| Frost and Sullivan 2024 China robotaxi report and related extracts | Cost per kilometre estimates for Chinese robotaxis in 2019 and 2023 and projected cost curves towards 2030. |

| Trade and technology press on Baidu RT6 and sensor pricing | Indicative per vehicle cost for Baidu’s latest robotaxi and order of magnitude drops in lidar prices over the past decade. |

| Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and Chinese city AV test reports | National demonstration zones, test road lengths, test licence numbers and overall autonomous mileage in China. |

| Uber and WeRide announcements for Abu Dhabi robotaxis | Evidence that Chinese suppliers are already exporting fully driverless services to the Gulf under the Uber brand. |

| European and international coverage of Baidu’s partnership with Lyft and PostBus | Planned launches of Baidu backed robotaxis in Britain, Germany and Switzerland and the use of Apollo software outside China. |

| Nvidia automotive and investor materials, plus coverage in financial press | Role of Nvidia GPUs and platforms as the common hardware and simulation layer for Tesla, Waymo, Baidu, WeRide and major carmakers. |

| Consultancy reports (BCG, McKinsey) on robotaxi cost comparisons | Benchmarks that place current robotaxi operations above ride hailing and private car costs and estimate the time needed to close the gap. |

| United States and Chinese policy documents and commentary | Differences between decentralised American regulation and integrated Chinese industrial planning around autonomous vehicles. |

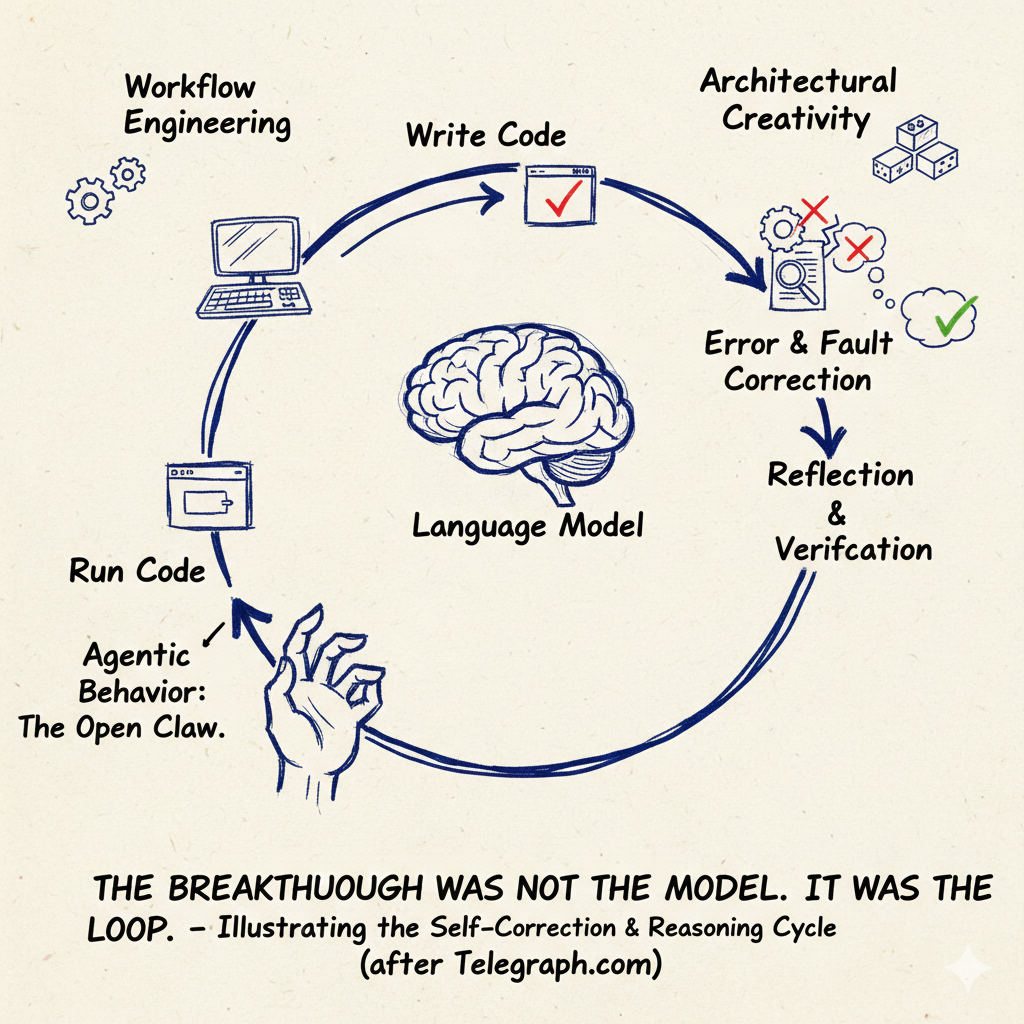

You may also like to read on Telegraph.com

Who Gets to Train the AI That Will Rule Us – On how control over the training layer of artificial intelligence quietly decides who governs the systems that stand between people and power.

The Quiet Land Grab Behind AI: Training Data and Who Gets Paid – Explains how AI firms capture value from data, why most contributors are unpaid, and how that logic will spill into autonomous transport.

When Prediction Becomes Control: The Politics of Scaled AI – Sets out how large scale predictive systems turn better forecasting into real political leverage, from welfare decisions to robotaxi networks.

The End of the Page: How AI Is Replacing the Web We Knew – Shows how AI assistants are already intercepting searches before they ever reach a web page, and what that means for public information.

The Super LLM Is Already Here – Argues that competing AI systems are converging into a de facto single intelligence as they watch, imitate and learn from each other’s outputs.

AI, Manipulation, and the Strange Loop – Examines how AI systems can shape beliefs and behaviour through subtle persuasion rather than brute force control.

AI Will Learn from Us and That’s What Should Terrify Us – Reflects on how a more capable intelligence may treat humans once it has learned from how we treat the species below us.

The Human Side Of Using A Very Large Machine – On how to work with large language models as assistants without surrendering judgement or agency to them.

London Leads Europe in AI, but Without Power and Capital the Advantage May Slip Away – Connects Britain’s AI ambitions to the hard constraints of energy supply and investment.

Editorial Verification Statement – Sets out Telegraph Online’s evidentiary standards, including how complex technology pieces like this robotaxi analysis are sourced and checked.