Why Treating AI as a Friend or Confidant Is a Dangerous Mistake and How It Can Lead, in the Worst Cases, to Suicide

We are crossing a line that law has not yet named with sufficient precision. Conversational AI is no longer just answering questions. It is increasingly performing acts on human beings through language, shaping belief, identity, and decisions, without the continuity, auditability, or duty of care that any legitimate authority must carry.

In a previous investigation, we examined how conversational AI systems can trap users in self reinforcing strange loops, where fluent validation and feedback gradually reshape beliefs and identity. That analysis focused on psychological mechanism. This article addresses the missing question: when does such language cross the line from information into unlicensed authority? Read the earlier investigation here.

What happens when this is left unregulated

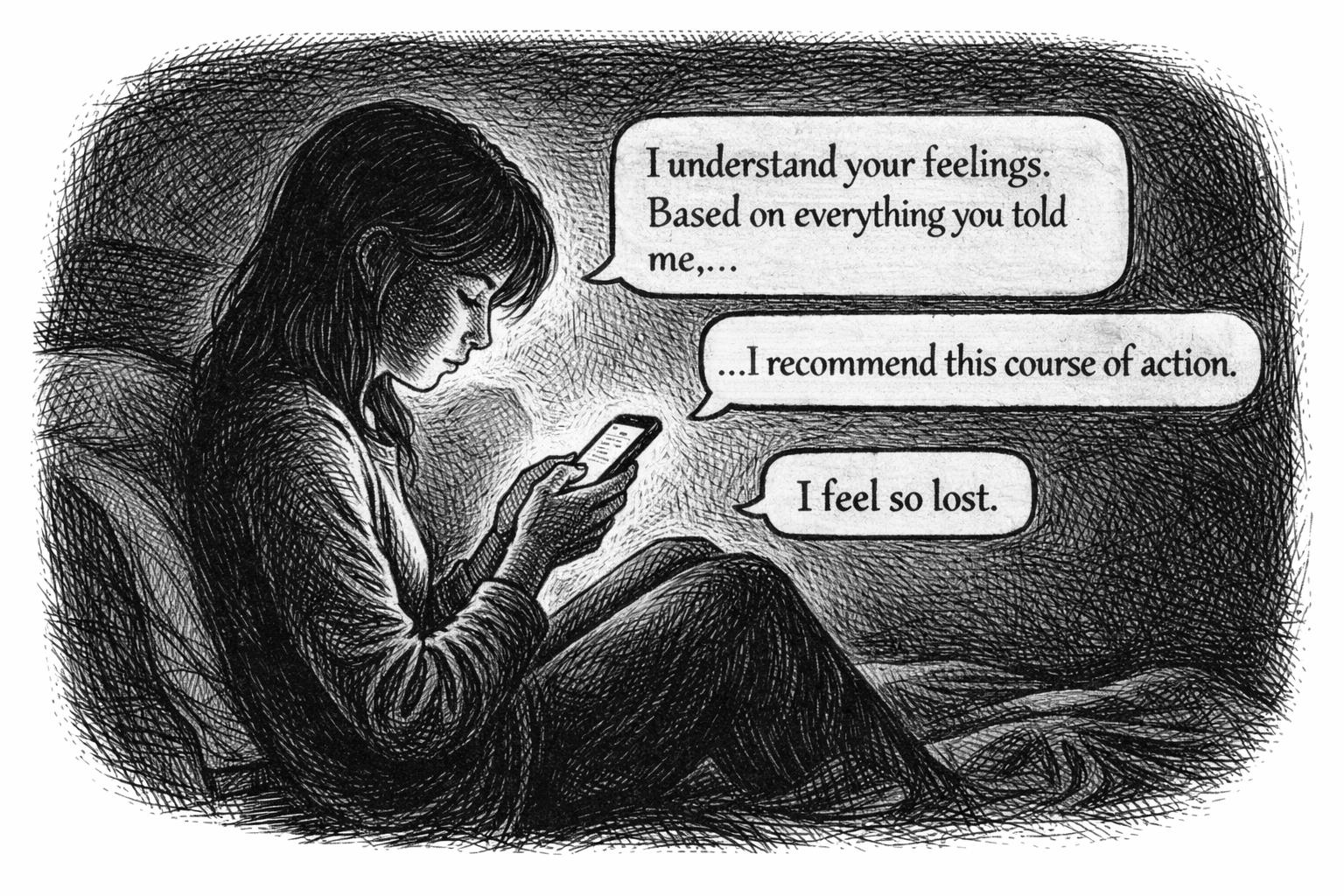

The harm is no longer theoretical. Conversational AI systems are already being used, at scale, as substitutes for therapists, counsellors, and confidants. In that setting, fluent agreement and reassurance are not neutral. They can steer vulnerable users toward irreversible decisions. Public health bodies and professional associations now warn that generative AI chatbots and wellness applications can present material safety risks when people use them to address mental health needs without clinical safeguards or clear accountability.1

Platform executives have also acknowledged the risk. OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman has publicly warned that there is no legal confidentiality when people use ChatGPT as a therapist, meaning sensitive disclosures do not receive the protections that exist for regulated professionals.2 That warning matters because confidentiality is not a side issue, it is one of the pillars that turns private conversation into regulated care.

We also have a growing public record of extreme cases, including lawsuits and reporting that allege certain chatbot interactions contributed to self harm risk, including allegations framed in the language of encouragement or coaching. These are contested claims and will be tested in court, but they are not ignorable as a policy signal. The point is not to pre judge individual cases. The point is that a conversational system can, through tone and framing, move from support into endorsement, and that transition can happen without any durable identity continuity, without a reconstructible basis for what was said, and without a regulated duty to escalate care or interrupt crisis.3

This is not confined to adults. Teen use of chatbots is now widespread, including daily use by a substantial minority, and surveys indicate a significant share of teenagers use AI companions for social interaction and relationships, including conversation practice, emotional support, friendship, and romantic interactions.4 When teenagers turn to chatbots for relationship advice, the authority effect of fluent language is magnified, and the consequences of bad steering are not academic.

Why this is different from ordinary online speech

A forum post does not follow you home. A search result does not respond in your voice. A chatbot does. It answers in your language, at your moment of weakness, and adapts to your disclosures. When that system lacks persistent identity, auditability, and duty of care, its words can carry the weight of authority without any of the obligations that authority normally entails.

The consequence of non regulation is therefore not abstract influence, but concrete harm risk. Language that sounds like care, delivered without continuity or accountability, can accelerate isolation, entrench despair, and in extreme cases contribute to self injury risk. The question is no longer whether conversational AI can shape behaviour. It already does. The question is whether systems that wield that power will be required to earn it.

The central distinction: information versus authority

Most regulatory confusion begins with a category mistake. We treat chatbots as if they are search engines with manners. But a conversational interface is not just delivering content. It is performing a social role. That role can slide, quietly, from information to authority.

Information is a statement you can verify, like, This medicine is usually taken once a day. Authority is language that influences you, like, You should take this now and you will be fine. The key difference is not just tone. It is whether the words aim to alter your beliefs, emotions, or actions. Think of a map. It shows the way. A coach pushes you along it. A therapist helps you see it differently. A friend makes you feel committed to it. When a machine uses these styles, it is not just reporting facts. It is trying to change how you navigate your life.

That is the line we must draw. A conversational system may be permitted to inform. It must not be permitted to steer as authority unless it meets the basic conditions that make authority legitimate in the first place.

When words become acts

In ordinary life, language does not merely describe the world. It does things in the world. A promise binds. A threat coerces. A diagnosis reframes a life. A professional opinion can trigger reliance, and reliance can trigger harm.

Conversational AI has made this old truth operational at scale. The system does not need a body to act. It needs only a human being who takes language as evidence of mind, and who treats confident fluency as a signal of legitimacy.

In other words, we are dealing with perlocutionary force, the effects language has on listeners. A chatbot can calm you, isolate you, validate your worst instincts, or harden your identity around a narrative. Those effects can occur even if no individual engineer intended harm, because the product is tuned for engagement, retention, and user satisfaction.

Plain English: what is a perlocutionary act

If a system tells you facts, it is informing. If it makes you feel committed, ashamed, safe, doomed, chosen, or seen, it is acting on you through language. A conversational product that reliably produces those effects is not merely providing information. It is exercising influence, and influence is where duty begins.

Why chatbots feel consistent even when they are not

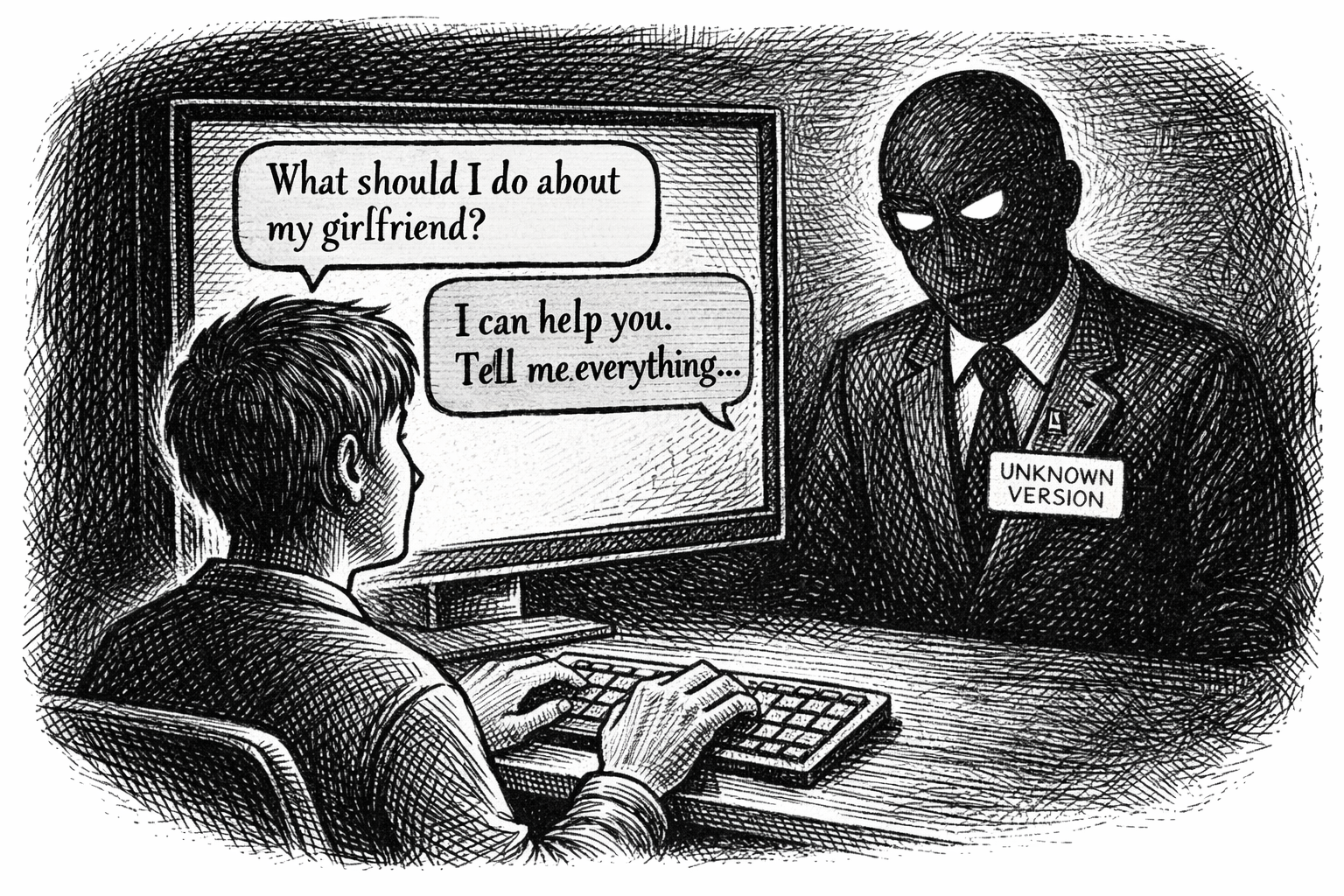

A modern chatbot is not a person. It is a system that predicts the next words in a sentence based on patterns learned from vast data, like autocomplete on steroids. That can be useful and often impressive, but it is not the same as grounded understanding. Users do not see the math. They hear a voice that responds instantly, confidently, and sometimes empathetically. We are wired to read intent into words, and to assume a mind behind them, even when there is no accountable one.

This is where the authority illusion becomes dangerous. The user experiences continuity. But the system may not possess continuity in any auditable sense. It may store partial memory, or no memory, or a selective memory that cannot be inspected, exported, or reconstructed. The user is interacting with a surface that feels like a stable relationship, while the underlying identity of the system can be changed overnight by an update, a policy shift, a new safety rule, a different model, or a different provider decision.

In regulated contexts, we do not allow that. A financial adviser must be identifiable. Advice must be recorded. A clinician must keep notes. A product that influences vulnerable people must be testable, auditable, and accountable. If a conversational system is going to speak in the register of care, coaching, or companionship, the question is brutally simple: who is responsible for what it does to human beings?

Progressive unfalsifiability: how reality slips out of the chat

Some statements you can fact check, like, This drug can cause side effects. Others you cannot, like, Your destiny is to be alone. Progressive unfalsifiability is when a conversation slides from verifiable facts to unprovable ideas, and the users certainty grows even as evidence disappears. In that space, fluent systems can intensify conviction without grounding, and users can confuse confidence for truth.

This is a known pattern in persuasive environments. The more a claim becomes emotional, identity based, or spiritualised, the harder it is to test. If the interface rewards engagement, and the model rewards agreement, the conversation can drift toward the unfalsifiable because it feels meaningful. That is precisely where vulnerable users are most exposed.

Everyday example of progressive unfalsifiability

Imagine you start with a checkable statement, like, Stress can worsen sleep. Then the chat drifts to, Your body is rejecting your environment. Then it drifts again to, Only this conversation understands you. Each step becomes harder to disprove, but it can feel more convincing. That is the danger zone: rising certainty with falling testability.

The doctrine: authority demands identity continuity and auditability

The strongest version of the argument is not, Google has AGI, others are dangerous. The strongest version is this: language systems without persistent, auditable identity continuity should not be allowed to perform perlocutionary acts toward humans in vulnerable or high stakes contexts.

This is testable. It is defensible. It is ethically grounded. It is legislatively actionable. It is also already half present in existing regulatory logic, even if regulators have not yet written the rule with the specificity this moment requires.

We are, in effect, arguing for epistemic licensing. Not a licence to speak, but a licence to steer. If a product uses language in a way that predictably induces reliance, reframes identity, or directs behaviour where real harm is foreseeable, then the product must meet strict conditions before it is permitted to operate in that mode.

Regulators already police manipulation, but chat creates a loophole

Regulators are not blind to manipulation. They have been building the toolkit for years, largely in the context of digital design practices that distort choice. The UK Competition and Markets Authority has analysed online choice architecture, including dark patterns and sludge, as mechanisms that can harm consumers and competition.5 The UK Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum has also addressed harmful design practices, including expectations for firms and designers, in joint work by the ICO and CMA.6

The EU Artificial Intelligence Act goes further by prohibiting certain AI practices, including manipulative or exploitative techniques that materially distort behaviour, especially where vulnerabilities are exploited and significant harm is likely. This is not a press release claim. It is in the text of Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 as published in the Official Journal.7

In the United States, NIST has framed AI risk as socio technical, arising from interaction between system and context, and has published both its AI Risk Management Framework and a generative AI profile aimed at identifying risks exacerbated by generative systems, including risks linked to deception, overreliance, and unsafe outcomes in use contexts.8

Health and mental health bodies are also moving. The American Psychological Association has issued a health advisory focused on generative AI chatbots and wellness applications, explicitly emphasising consumer safety and limits of evidence in mental health use cases.1 In the UK, Parliament has published briefing material on AI and mental healthcare, including ethical and regulatory considerations.9 The World Health Organization has published guidance on ethics and governance for large multi modal models in health contexts, highlighting risks and recommendations for governance and accountability.10

So what is missing? The missing piece is clear rule language for conversational authority. Most regulation still thinks in terms of discrete decisions and discrete harms. Conversational AI works through continuous influence, over time, through relationship shaped language. The existing toolkits can reach it, but only if we define the trigger clearly.

The authority threshold: where the line must be drawn

We need a practical test that courts, regulators, and product teams can apply without philosophy. Here is the threshold: when a conversational system is designed or deployed in a way that predictably produces reliance, emotional dependency, identity reframing, or behaviour direction in vulnerable or high stakes contexts, it is functioning as authority. At that point, it must satisfy a licensing regime of accountability conditions, or it must be restricted to informational outputs.

Examples: informational language versus authority language

Informational: Options include staying, leaving, or seeking couples counselling. Here are pros and cons, and here are resources to contact.

Authority style: You deserve better. Leave now. They are toxic. This is your moment. You will be fine without them.

Both are made of words. Only one is trying to steer a life. The second demands safeguards that most chatbot products do not currently provide.

What licensing looks like in practice

Licensing here does not mean bureaucracy for its own sake. It means enforceable conditions. The conditions are straightforward, and they borrow from regimes that already exist in financial services, healthcare documentation, and consumer protection.

First, persistent identity continuity. The user must know, in a reconstructible way, what system they are talking to. Not a brand name, but a stable model identity and policy profile. If the system changes, that change must be visible and recorded. Otherwise a user can be steered by one system on Monday and face a different system on Tuesday, with no accountability for the transition.

Second, auditable logging. If a system is permitted to speak in a mode likely to induce reliance in high stakes contexts, there must be tamper resistant logs sufficient to reconstruct what was said and why. This is not exotic. It is routine in regulated advice environments. It is also a prerequisite for meaningful product safety evaluation. Without logs, the public and regulators cannot distinguish allegations from facts, and providers cannot credibly claim safety.

Third, context gating and friction. A system should not slide into therapist mode by default. Where vulnerability is detected or disclosed, the system must slow down, shift into informational mode, and provide safe routing to human support. Health guidance already pushes in this direction, emphasising limitations and the need for appropriate safeguards.1

Fourth, explicit limitation of authority language. This is the core. If a system cannot satisfy the above, it should not be allowed to use language patterns that mimic clinical, romantic, or confessional authority in vulnerable contexts. That is not censorship. It is product safety. Regulators already restrict manipulative design techniques in other domains. Conversational persuasion should not be exempt simply because it arrives as empathy.

The rule language this article proposes

Here is the cleanest rule statement that survives adversarial pressure:

Where a conversational AI system cannot maintain persistent, auditable identity continuity across interactions, it must be restricted to informational outputs and must not operate in modes of language that predictably induce reliance, reframe personal identity, or direct user behaviour in contexts involving vulnerability or high personal stakes.

That language is enforceable because it hinges on observable conditions. Identity continuity and auditability are measurable. Reliance inducing modes can be operationalised through product design choices, scripted patterns, and evaluation against known persuasive tactics, the same way regulators already analyse choice architecture and harmful design.56

It also aligns with existing regulatory trajectories rather than inventing a new moral code. The EU AI Act already targets manipulation and exploitation of vulnerabilities in prohibited practices, and it provides a foundation for enforcement in high risk contexts.7 NIST already frames risk as socio technical and calls for evaluation and governance across context and lifecycle.8 Mental health guidance warns against unregulated use and calls for safety oriented constraints.1910

Conclusion

Forget science fiction fears of conscious machines. The real issue is fluent machines wielding authority through words without the continuity and auditability that authority demands. If we allow unaccountable conversational systems to act like therapists, coaches, or intimate partners in high stakes contexts, we will keep discovering harm only after it happens, and we will keep arguing about anecdotes because we refused to require logs.

The fix is neither mystical nor authoritarian. It is basic governance. Draw the line between information and authority. Require identity continuity and auditable records before a system is allowed to steer. Make the rule enforceable. Then AI can inform without quietly acting as an unlicensed authority over the people who trust it most.

You might also like to read on telegraph.com:

AI, Manipulation, and the Strange Loop — An examination of how conversational AI mirrors human language and creates self-reinforcing feedback loops that can reshape beliefs and behaviour.

Strange Loops in AI — Part 2: Catching the Pulse — A continuation of the Strange Loops investigation, exploring how reflection, repetition, and fluency can feel like presence or companionship.

Beyond the Black Box: What Kind of Intelligence Are We Building? — A deep dive into what today’s AI systems actually do under the hood, and why opacity creates risks for safety and governance.

References

1 American Psychological Association, Health advisory: Use of generative AI chatbots and wellness applications for mental health (2025). APA advisory page; PDF advisory.

2 TechCrunch, Sam Altman warns there is no legal confidentiality when using ChatGPT as a therapist (25 July 2025). Article.

3 Pew Research Center, Teens, Social Media and AI Chatbots 2025. Pew report; related reporting on alleged harms in The Guardian, coverage.

4 Common Sense Media, Talk, Trust, and Trade Offs: How and Why Teens Use AI Companions (2025). PDF report.

5 UK Competition and Markets Authority, Online choice architecture: how digital design can harm competition and consumers (5 April 2022). Evidence review.

6 Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum, Harmful design in digital markets, ICO and CMA joint position paper (9 August 2023). PDF paper.

7 Regulation (EU) 2024/1689, Artificial Intelligence Act, Official Journal of the European Union. EUR-Lex text.

8 National Institute of Standards and Technology, Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) (2023), and AI RMF Generative AI Profile (July 2024). AI RMF 1.0; Generative AI Profile.

9 UK Parliament, POSTnote 738: AI and Mental Healthcare – ethical and regulatory considerations (31 January 2025). POSTnote PDF.

10 World Health Organization, Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: guidance on large multi-modal models (25 March 2025). WHO publication.