HS2 as Mirror: How Britain Lost the Ability to Build, Govern, and Deliver

In the middle of the nineteenth century, Britain did not hesitate before it built.

Under Isambard Kingdom Brunel, railways were driven through hills, bridges were thrown across rivers, and tunnels were cut through chalk and granite with a confidence that now feels alien. These were not ornamental projects. They were instruments of national purpose, executed by a state that believed it could organise itself to do hard things.

Victorian Britain argued ferociously about routes, costs, and risk. But once decisions were made, the state retained control. Engineers answered to ministers. Contractors delivered to specification. Failure was personal. Responsibility was clear.

That confidence has evaporated.

Modern Britain still announces big projects. It still spends heavily. But when it tries to build, it loses control of time, cost, and outcome. When it faces emergencies, it pays quickly and checks later. When projects unravel, accountability dissolves into arm’s length bodies, consultants, and process.

HS2 is not an anomaly. It is a mirror.

The central charge

Britain’s problem is not simply waste or misfortune. It is the loss of state competence: the ability to design, commission, control, and deliver complex systems without surrendering authority to contractors, consultants, or process.

HS2 began as a statement of national intent: a high speed rail spine connecting London, the Midlands, and the North. Fifteen years later, it has become something else entirely. The route has been truncated. The timetable repeatedly reset. The cost has swollen to a figure so large that ministers now avoid saying it aloud.

Even on conservative official estimates, HS2 is on course to become the most expensive railway per kilometre ever constructed. That fact alone would be extraordinary. What makes it damning is the context.

HS2 is not cutting through alpine rock or navigating earthquake zones. For long stretches, it crosses gently rolling countryside. And yet, measured on a purchasing power parity basis, its cost per kilometre exceeds that of high speed rail projects anywhere in the world.

This did not happen because Britain forgot how to pour concrete or lay track. It happened because the project was authorised before it was designed, contracted before its risks were understood, and managed through a structure that rewarded spending rather than discipline.

Parliament approved the first phase when design completion stood at roughly four percent. Scope was locked in through bespoke legislation, limiting flexibility once engineering realities emerged. Large contracts were signed on a cost plus basis, guaranteeing contractors higher returns as costs rose. Technical authority sat with suppliers rather than the state. Network Rail, with decades of delivery experience, was marginalised.

What followed was not bad luck. It was inevitability.

HS2 in international context

Britain now pays more per kilometre for HS2 than Japan, France, Italy, or China pay for high speed rail built through mountains, under cities, or across seismic terrain. The difference is not geography. It is governance.

HS2 exposes a broader transformation in how Britain now governs.

Over time, the civil service has shed technical expertise. Engineers, delivery specialists, and project managers have been replaced by commissioners, overseers, and assurance professionals. Capability has not disappeared; it has been externalised.

The modern British state does not design systems. It procures advice about systems, then hires contractors to implement that advice, then commissions further reviews to explain why implementation failed.

This model produces predictable outcomes. Control migrates to suppliers. Incentives invert. Responsibility fragments. Failure becomes procedural rather than personal.

If HS2 shows how Britain fails slowly, the pandemic shows how it fails under pressure.

Covid demanded speed, logistics, and disciplined procurement. Britain moved fast, but it did not retain control. Normal safeguards were suspended. Contracts were issued at pace. Oversight weakened. What followed was not merely high expenditure, but extraordinary waste.

Billions were spent on personal protective equipment that could not be used. Warehouses filled with unusable stock. Storage and disposal costs mounted. Emergency schemes leaked fraud and error at scale.

Emergency as system test

In emergencies, states reveal their true capacity. Britain revealed a system that could authorise spending rapidly, but not enforce discipline once money left the Treasury.

Comparisons with China are uncomfortable, but unavoidable.

When Covid struck Wuhan, China constructed a fully functioning hospital in ten days. This was not improvisation. It was mobilisation: standardised design, central authority, and command of resources.

China’s high speed rail network tells the same story. Tens of thousands of kilometres built in little more than a decade. Unit costs dramatically lower. Designs replicated rather than reinvented. Contractors serving a centrally directed system.

The capacity gap

China standardises. Britain bespoke-ifies.

China retains expertise in the state. Britain rents it.

China controls contractors. Britain negotiates with them.

If HS2 feels abstract, the Garden Bridge does not.

The proposed Thames crossing championed during Boris Johnson’s mayoralty was never built. Yet more than fifty million pounds were spent before cancellation. A special purpose body was created. Governance blurred. Political enthusiasm substituted for delivery discipline. When support evaporated, the project collapsed. The funds did not return.

This was not a megaproject. It was a small civic scheme. And yet it reproduced the same institutional pattern.

The NHS tells the same story, only more slowly.

Hospitals across England carry a vast backlog of maintenance. Ageing buildings leak heat, water, and productivity. Infrastructure failures disrupt care and force expensive workarounds. Preventive maintenance deferred becomes emergency repair multiplied.

Maintenance as state capacity

States that maintain assets cheaply can build new ones confidently. States that defer maintenance pay repeatedly for decay.

Roads provide the most visible evidence of Britain’s decline.

Potholes proliferate. Resurfacing cycles stretch into absurdity. Councils patch rather than rebuild because funding is unpredictable and fragmented. The result is higher lifetime cost and lower public trust.

Even defence procurement now carries the same signature.

The aircraft carriers HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales were conceived as symbols of national power. In practice, both have suffered repeated availability and propulsion issues. These are not trivial teething problems. They reflect procurement systems that prioritise headline capability over resilience.

One signature, many sectors

Rail. Health. Roads. Defence. Emergency procurement.

Different domains. Identical logic: authority outsourced, expertise rented, incentives misaligned, accountability diluted.

Britain did not lose its ability to build overnight. It chose a governing model that replaced command with commissioning, expertise with consultancy, and responsibility with process.

The state now generates documentation, not delivery. Reviews proliferate. Concrete lags.

HS2 is embarrassing not because it is expensive, but because it is honest.

It reveals Britain as a country still wealthy enough to spend, but no longer competent enough to control outcomes. In an era of geopolitical stress and systemic competition, state capacity is not a technocratic detail. It is national power.

Brunel’s Britain believed the future could be shaped. HS2’s Britain negotiates with its own limitations.

That is the mirror. And it does not lie.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

Britain’s Pressure Economy: Why 2026 Will Test Housing, Bills, and Social Order

A forensic look at the household tripwires behind arrears, eviction, and rising enforcement, and why the pressure is economic before it is political.

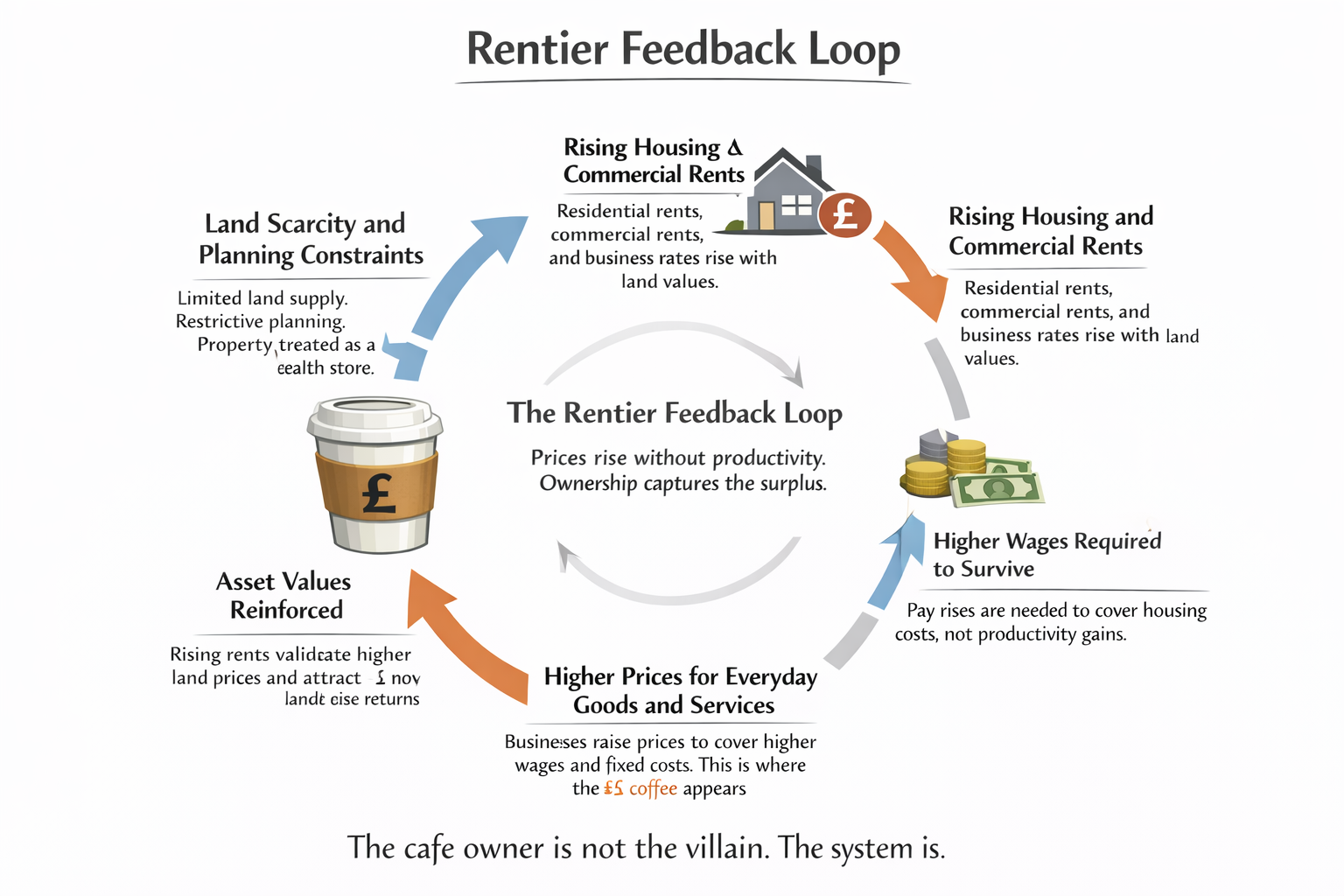

The Rent Crisis Was Manufactured: To Serve Profit, Not Shelter

How policy choices turned scarcity into extraction, and why housing became a transfer system from wages to property holders.

Sex for Rent Scandal: Landlords Exploit Britain’s Broken Housing Market

A case study in what happens when housing scarcity meets vulnerability, weak enforcement, and a market that rewards coercion.

The Sick Man of Europe, Again: Britain Enters the Great Crisis

Stagnation, service strain, and the national conditions that turn housing stress into wider social fracture and political volatility.

Britain’s Borrowing Costs Surge to 27 Year High, Reviving Old Fears of Fiscal Strain

When the cost of money rises, the squeeze travels quickly from the Treasury to mortgages, rents, and the cost of everyday survival.

Rachel Reeves UK Budget 2025: A Critical View

An inequality lens on fiscal choices, who absorbs the loss, and how distributional decisions harden poverty over time.

Britain’s Polarisation: Why Farage Is Winning

A numbers first account of division driven by wages, housing, and failing services, rather than the headline culture war explanations.

Fifth Floor, Christmas Day

A winter essay that puts the housing and poverty arithmetic on the page, anchored to homelessness and temporary accommodation realities.

Everything Here Follows the Rent

A ground level portrait of how rent pressure reshapes dignity, family stability, and the lived experience of insecurity.

Britain’s Quiet Crackdown: How Insurance, Courts, and Banks Are Building the 2026 Order

How administrative systems standardise enforcement and exclusion long before the public debate catches up.

Britain’s Migration Crackdown Is Quietly Gutting Its Future

A capacity argument about skills, tax base, and the political economy that inflates property while weakening productive foundations.

The Shadow Bank That Wants Your Savings

Private credit moving toward ordinary savers, and why hidden leverage tends to surface during household stress cycles.

Property Rights, Sanctions and the Abramovich Test for Britain

On British law, property, and credibility, and what happens when the rules feel contingent rather than dependable.

When Britain Turns Trust into a Weapon, It Cuts Its Own Throat

A hard look at how Britain’s prosperity depends on institutional credibility, and what follows when credibility is treated as expendable.

Digital ID and the Shadow of Control

A warning about how fraud framing can expand conditional access and deepen the exclusion of those already living on the edge.