Shadows Behind Closed Doors: How Labour Together Rose From Defeat to Power

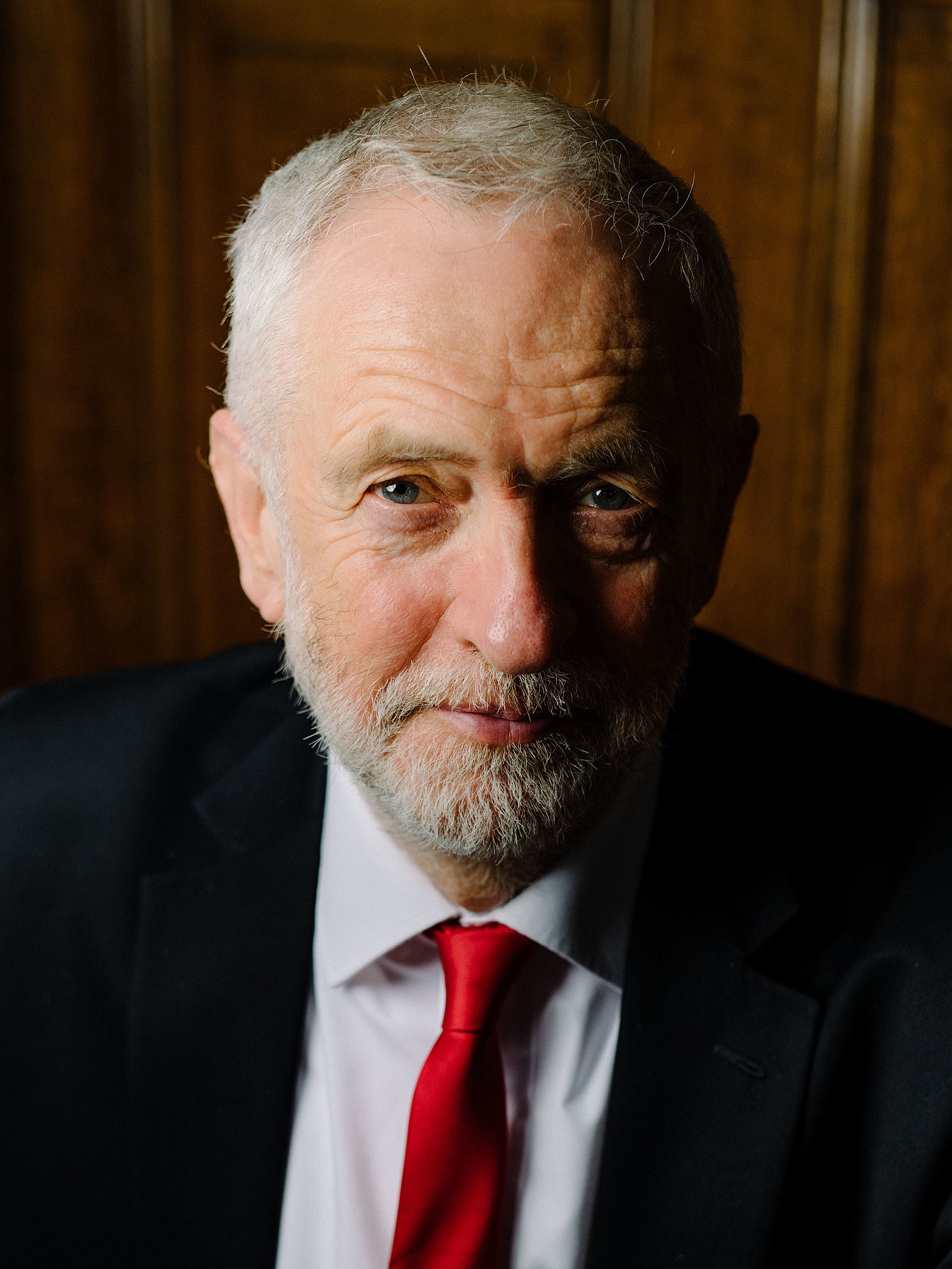

The summer of 2015 was heavy with dread in the Labour Party. A bruising general election defeat had left the party disoriented, and the sudden rise of Jeremy Corbyn a backbencher with a record of defying his own leadership stunned Westminster. MPs were in disbelief: Corbyn had harnessed a wave of anti-austerity anger that electrified the grassroots, even as Labour’s parliamentary ranks feared catastrophe at the polls.

The membership was swelling by the tens of thousands, drawn by promises to renationalize railways, scrap tuition fees, and reverse austerity. Inside the Parliamentary Labour Party, alarm bells rang. Contemporary reporting described MPs as “aghast,” fearing both their own careers and Labour’s path back to government were imperiled.

Alongside doubts about electability came another crisis. In July 2018, Margaret Hodge confronted Corbyn in the House of Commons and accused him of being “a racist and antisemite,” according to The Guardian. Her words triggered a party inquiry, though the case was later dropped. Hodge later argued that Labour had become “a hostile environment for Jews,” a claim widely cited in subsequent coverage.

It was out of this atmosphere — disbelief among MPs, loyalty among grassroots members, questions over foreign policy, and rows over antisemitism — that a small network began to plan. Their answer, was not open rebellion but something quieter: an internal machine that could chart a different future. By the end of 2015, those discussions had coalesced into a project. The name would change — from Common Good Labour to Labour Together — but the intent was clear: a vehicle to prepare for the post-Corbyn era.

Building the machine

As The Guardian later reported, early strategy papers considered three options: back Corbyn, split and form a centrist party, or build a faction within Labour that could bide its time. The third path — slow, deliberate institution-building — won out.

By 2017, Companies House filings confirm that Morgan McSweeney, who had run Liz Kendall’s leadership campaign, became director. Under his leadership, Labour Together “grew into a data-driven outfit,” according to The Times. The paper described how McSweeney focused on polling, slicing the membership into categories — core ideologues, pragmatic “instrumentalists,” and younger “idealists” who might be persuaded by soft-left promises.

Labour Together styled itself as a think tank, but critics on the left saw it as something more. As Jacobin magazine put it, “an elite-funded factional vehicle,” pointing to the flow of donations from wealthy individuals. Its backers, The Guardian reported, rejected that label, insisting it was a unifying force that could provide serious policy work and rebuild Labour’s credibility.

The money

The question of funding would later become a flashpoint. In 2021, the Electoral Commission fined Labour Together £14,250 for failing to properly report more than £739,000 in donations between 2017 and 2020. The Commission noted multiple breaches but did not allege deliberate concealment.

According to Novara Media, Martin Taylor — a hedge fund manager who founded Nevsky Capital and later ran Crake Asset Management — donated around £585,992 during that period. Sir Trevor Chinn, described by Novara as a long-time Labour donor and philanthropist, gave around £175,500. Donor registries have also listed him as an adviser at CVC Capital Partners. And according to The Guardian, Gary Lubner, the former chief executive of Belron (Autoglass), later emerged as another major backer, contributing around £600,000 after Keir Starmer became leader.

Critics cited by Jacobin and Novara argued that Labour Together became a magnet for high-net-worth donors who wanted a centrist Labour capable of governing. Supporters countered, in interviews reported by The Guardian, that such funding was essential to compete with the Conservatives’ donor base.

Corbyn’s near-miss

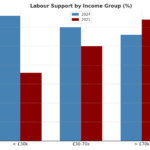

The 2017 snap election briefly upended these calculations. Against expectations, Corbyn’s Labour won 40 percent of the vote and denied Theresa May her majority. For a moment the “unelectable” leader appeared to have reshaped the political map.

But the momentum did not last. By 2019, Brexit gridlock, continuing rows over antisemitism, and questions over national security had eroded trust. Labour slumped to 32 percent in the general election, its worst result since 1935.

According to The Guardian, Labour Together’s research under McSweeney mapped paths to rebuilding Labour’s appeal, especially to voters in “red wall” seats. It seeded reports, convened MPs, and positioned itself, the paper said, as a clearinghouse for strategy in anticipation of the next leadership contest.

Finding their man

When Corbyn resigned after the 2019 defeat, Labour Together’s preparation met its moment. Both The Guardian and The Times noted the group’s influence in Keir Starmer’s leadership bid. McSweeney became campaign director, and Labour Together’s infrastructure provided polling, messaging, and networks of support.

Starmer’s “Ten Pledges” echoed elements of Corbyn’s platform — free tuition, investment in public services — but reassured centrist MPs and donors that the party would pivot toward electability. In April 2020, Starmer won the leadership with 56 percent of the vote, defeating Rebecca Long-Bailey, Corbyn’s chosen successor.

McSweeney later joined Starmer’s staff as chief of operations, before becoming chief of staff in Downing Street. Labour Together itself shifted into a more conventional think tank role, publishing papers on “securonomics,” green investment, and digital IDs. According to Companies House, its board expanded to include Baroness Sally Morgan, Lord Jonathan Kestenbaum, lobbyist Michael Craven, philanthropist Francesca Perrin, and migration policy specialist Will Somerville.

The donations row reignites

In September 2025, the issue of Labour Together’s finances returned to the headlines. As The Times reported, leaked emails showed that a Labour lawyer had advised McSweeney to attribute undeclared donations to “admin error.” The Conservative Party demanded a fresh inquiry. But as Sky News reported, the Electoral Commission declined to reopen its investigation, saying it found “no evidence of any other potential offences.”

Labour insisted — in statements reported by The Guardian — that Starmer’s 2020 campaign had paid McSweeney directly, not Labour Together, and therefore no undeclared in-kind support had been received. Critics, cited in The Times, were unconvinced, but regulators appeared satisfied.

The legacy of Labour Together

Today, as The Guardian has described, Labour Together stands as one of the most influential forces in British politics. Its critics, like former ally Jon Cruddas, have called it “right-wing” and “illiberal.” Supporters, in interviews cited by The Times, see it as the engine that lifted Labour back into government after a decade of Conservative rule.

What is clear, according to multiple press accounts, is that Labour Together was born in crisis. In the closed door rooms of 2015, moderates feared annihilation at the ballot box, divisions over foreign policy, and allegations of antisemitism. They chose the long game: to build a machine that could outlast Corbynism and prepare a centrist revival.

A decade later, that machine has delivered. Labour Together is no longer working in the background but drafting the policies of a governing party. Yet the question that haunted its birth remains unresolved: whether Labour’s soul belongs to its grassroots members or to the donors who funded its return to power.