Xi Jinping, Corruption, and the Chain of Command Inside China’s PLA

The sudden removal of two senior PLA generals has triggered speculation about power struggles at the top of the Chinese system. No one outside the Party knows the full truth. This essay examines what is known, what is conjecture, and why the balance of evidence points most strongly to corruption rather than a crisis of loyalty.

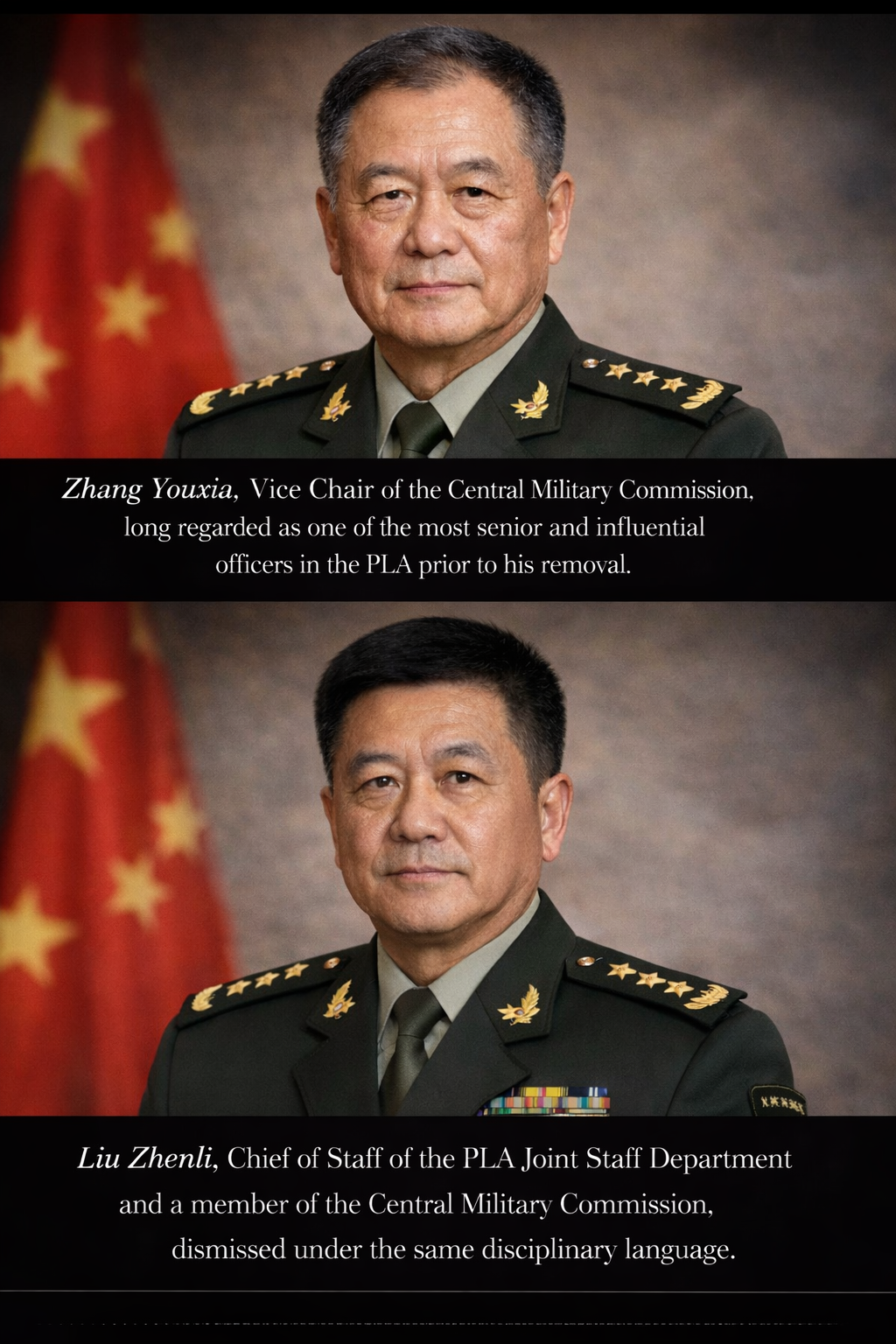

Composite image of Zhang Youxia and Liu Zhenli with identifying captions.

What this article is and is not

The removal of two of China’s most senior military officers has produced an almost reflexive response outside the country speculation. Was this a factional struggle inside the People’s Liberation Army. A warning shot ahead of a future leadership transition. Evidence of instability at the core of the Chinese system.

The truth is more prosaic and more difficult. No one outside the Chinese Communist Party leadership knows for certain why these generals were removed. The Chinese system does not publish indictments trial evidence or internal deliberations at the moment disciplinary action is announced. What it does publish is language precise repeatable carefully chosen language and in the absence of transparency that language is the most reliable guide available.

This article does not claim privileged insight. It does not allege coups or hidden plots. It does not treat conjecture as evidence. Instead it proceeds on three narrow grounds. First it sets out what is known using only publicly verifiable facts and official wording. Second it places those facts within the institutional and historical context of how the Party disciplines its armed forces. Third it weighs competing explanations and explains why judged against precedent and structure corruption and corruption linked discipline violations remain the most likely cause even if political discipline is also being enforced.

This is an attempt to replace drama with structure and speculation with probability.

What happened stripped to facts

Two senior figures in the People’s Liberation Army were placed under investigation. One was the vice chair of the Central Military Commission the body that commands China’s armed forces. The other was a CMC member and chief of staff one of the highest ranking operational officers in the military.

The announcement did not allege a plot. It did not cite treason. It did not claim disloyalty to a named leader. Instead the military’s official newspaper accused the two men of serious violations of discipline and law and of damaging the chairman responsibility system the constitutional principle that places the armed forces under the Party’s absolute control.

That phrasing matters. In the Chinese system words are chosen with care. When the Party believes it faces an immediate security threat it says so. When it confronts institutional misconduct it reaches for discipline language. Here the Party chose the latter.

Why the wording matters

The chairman responsibility system is not a slogan. It is the formal doctrine that ensures the Party and specifically the Party leadership exercises final authority over the gun. Under China’s constitutional structure the chair of the Central Military Commission has supreme decision making power over the armed forces.

To accuse senior officers of damaging that system is not to allege rebellion. It is to allege institutional disobedience the accumulation of authority influence or autonomy beyond what the system permits. Such language does not require a conspiracy. It requires only a deviation from discipline.

This distinction is critical. Western commentary often collapses any reference to command authority into a narrative of personal rivalry. The Chinese Party state does not operate that way. It polices structures first personalities second.

What the Chairman Responsibility System Means

The chairman responsibility system is the constitutional mechanism that ensures the Communist Party’s absolute control over the military. It places final authority over strategic decisions promotions and doctrine in the hands of the Party leadership. Violations of this system do not imply rebellion. They imply the emergence of authority outside approved channels. In the Party’s logic such autonomy is itself a threat even absent overt disloyalty.

Xi’s 2012 mandate two legitimacy repairs

When Xi Jinping assumed power he identified two problems that threatened the Party’s long term legitimacy corruption and pollution. One undermined faith in rule. The other poisoned daily life. Together they signalled a system drifting away from the people it governed.

These were not abstract concerns. Corruption had become embedded across bureaucracies including the military. Pollution had become impossible to ignore choking cities and fuelling public anger. Xi’s promise was simple and politically resonant clean up the air and clean up the system.

Both campaigns were framed not as ideological exercises but as tests of state capacity.

Corruption as a system problem

The anticorruption campaign that followed was not episodic or symbolic. It became permanent infrastructure. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the National Supervisory Commission evolved into standing enforcement bodies processing cases at scale year after year.

In Party logic corruption is not primarily a moral failing. It is a structural danger. It creates alternative loyalty networks patronage chains and power centres that dilute central authority. In civilian institutions this is corrosive. In the military it is intolerable.

This is why corruption cases in the PLA are treated with particular severity. The Party does not distinguish neatly between financial misconduct and political discipline. Both weaken command.

Serious Violations of Discipline and Law

This phrase is the Party’s standard formulation for senior removals. It covers bribery procurement fraud abuse of authority and breaches of political discipline. Its purpose is not to obscure wrongdoing but to preserve flexibility the Party signals guilt without publishing details allowing investigations to proceed internally before formal charges or trials are announced.

The PLA’s forgotten commercial empire

To understand why corruption became so deeply embedded in the military it is necessary to return to the reform era. After Deng Xiaoping the PLA was encouraged to support itself financially. It ran factories hotels transport firms construction companies and trading houses. Entire local economies revolved around military owned enterprises.

This arrangement generated enormous wealth. It also generated rent seeking kickbacks and informal levies. Officers controlled assets. Units extracted percentages. Promotion and profit became entangled.

By the time Xi came to power the PLA was not only a fighting force. It was a sprawling commercial network rich fragmented and politically dangerous.

Why a Party Army Cannot Be a Business Empire

Commercial activity creates incentives incompatible with discipline. Wealth generates autonomy. Autonomy produces patronage. In a party army system loyalty must flow upward not outward. Allowing officers to accumulate independent economic power corrodes the chain of command even if no political challenge is intended.

Separating the gun from the cash

One of Xi’s earliest and most consequential moves was to strip the PLA of its commercial interests. Military businesses were divested or closed. Procurement was centralised. Political commissar oversight was strengthened.

This was not a cosmetic reform. It dismantled entrenched networks and displaced powerful interests. But removing business from the military does not end corruption. It relocates it into procurement contracts promotions and access to resources. That reality necessitates continued enforcement.

The logic is unforgiving. Once the Party commits to separating the gun from the cash it must keep pulling the thread.

Precedent matters

This is not the first time senior military figures have been removed under corruption charges. In recent years defence ministers and commanders linked to the Rocket Force China’s most sensitive strategic arm were formally expelled from the Party for bribery and abuse of position.

Those cases included Li Shangfu the former minister of national defence and Wei Fenghe his predecessor both of whom had overseen critical weapons and procurement portfolios and who as publicly announced by the Party were expelled for bribery and abuse of position. In each case the language was familiar. Serious violations. Discipline and law. No talk of plots. No invocation of treason.

The pattern is consistent rank does not confer immunity. Proximity does not protect. Strategic importance does not excuse misconduct.

Pattern Recognition in PLA Discipline

When the Party removes senior officers it uses standardised language proceeds incrementally and often expands investigations later. This is not crisis management. It is governance by discipline. The absence of drama is itself a signal of continuity.

Pollution as proof of state capacity

The parallel campaign against pollution reinforces this reading. Cleaning China’s air required shutting factories disrupting local economies and confronting vested interests. It was politically costly. Yet it proceeded because visible improvements in daily life strengthened legitimacy.

Anticorruption works the same way though its effects are less visible. Both campaigns demonstrate a willingness to accept disruption in pursuit of control and credibility. Together they form the spine of Xi’s governing philosophy.

Why corruption remains the most likely explanation

Pulling these threads together yields a disciplined conclusion. The Party used standard corruption language. There is strong precedent. There are no public indicators of emergency or instability. No allegation of disloyalty has been made. No extraordinary measures have followed.

This does not exclude political discipline. In the Chinese system corruption and political control are intertwined. But the balance of evidence points toward corruption or corruption linked discipline violations not a sudden crisis of loyalty.

Probability not certainty is the appropriate standard.

What this signals and what it does not

The removals signal zero tolerance for autonomous power inside the military. They signal continuity in enforcement. They signal that no rank is untouchable.

They do not signal imminent instability. They do not imply a coup attempt. They do not suggest a system in crisis.

Conclusion continuity not drama

Since 2012 Xi Jinping’s project has been consistent remove wealth from politics remove cash from the gun and restore the Party’s absolute authority over the institutions that matter most. The PLA sits at the centre of that project.

Seen in that light the removal of two senior generals is not a rupture. It is a continuation disciplined disruptive and deeply rooted in the logic of Party rule.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

-

China Converts Thousands of Soviet Era MiG 19 Jets Into Drone Swarms

An analysis of how China is repurposing legacy aircraft into mass drone capability. -

Chinese General Says Taiwan Could Be Taken With Conventional Arms

A PLA perspective on conventional military options and deterrence messaging. -

Luohe and the Escort Screen That Turns China’s Catapult Carriers Into Real Power

How China’s naval escorts transform carrier operations into credible force projection. -

China Bets on Discipline in the AI Race

Why China is prioritising control and coordination over speed in artificial intelligence. -

The World Order Is Quietly Turning From Caracas to the Arctic

A systems view of how China fits into shifting global power alignments. -

Pyongyang’s Parade Becomes a Bloc Summit

China’s role in the emerging East Asian and Eurasian strategic bloc. -

A Test of Nerves Over Vaindloo

How Russia and China shape pressure points along NATO’s periphery.