From the Front: How Winter, Fog and Silence Are Deciding the War in Ukraine

B y mid winter, the war in Ukraine no longer moves in lines. It moves in windows.

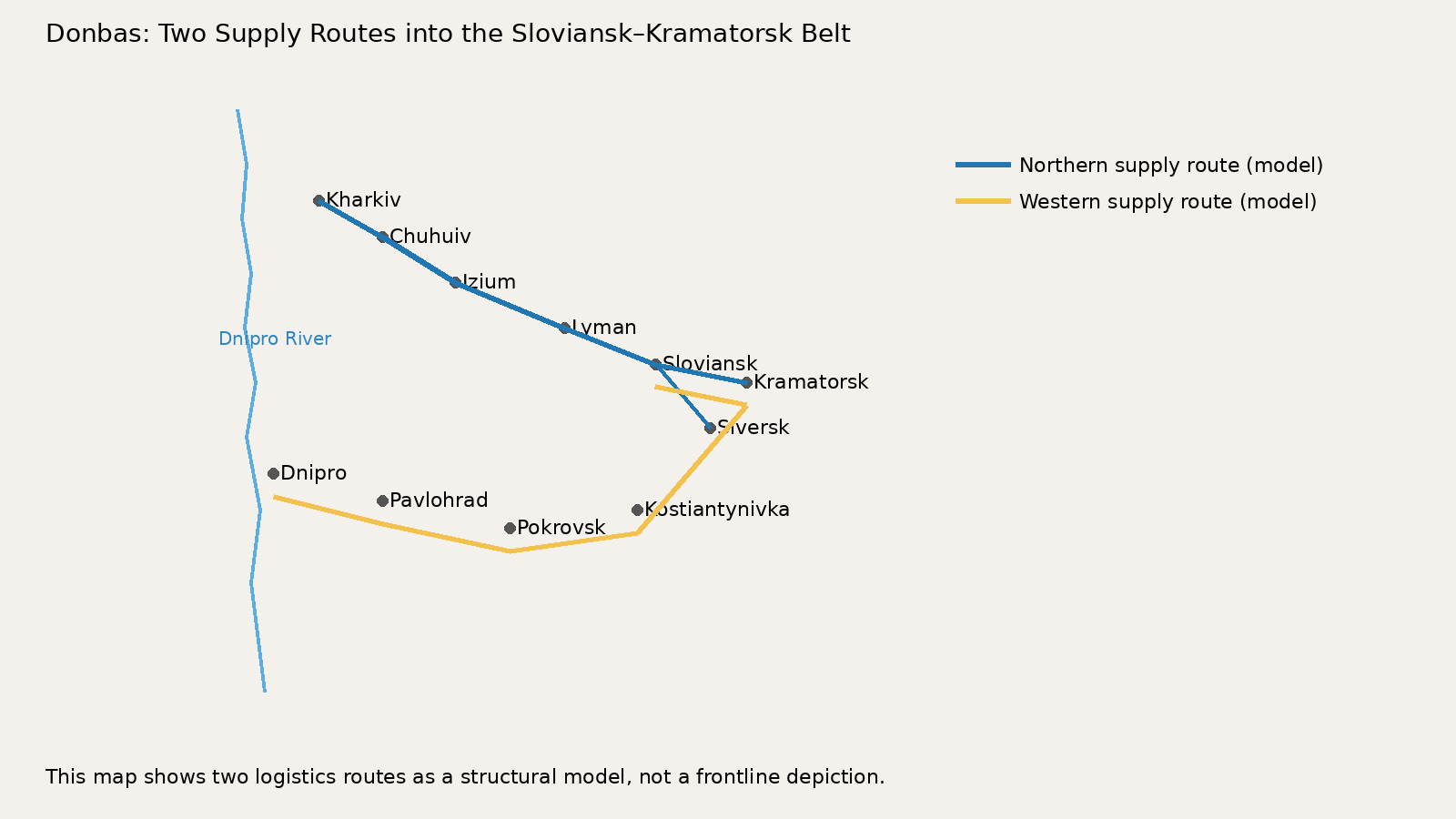

Across the front that stretches from the southern outskirts of Zaporizhzhia, through Huliaipole, up into Kostiantynivka, Chasiv Yar, Kramatorsk, Sloviansk, and north toward Lyman, combat has become governed by conditions rather than calendars. The decisive factor is no longer how many units can be assembled, but when the fog descends, when the rain begins, when the wind rises enough to ground drones.

This is a war that waits for weather and then exploits it.

The winter that never settles

Winter here is not a single state. It is a cycle that never resolves.

At night, temperatures plunge well below freezing. By late morning, they rise just enough to soften the surface. Then, as evening approaches, they fall again. The ground freezes, thaws, refreezes but never long enough to harden, never long enough to dry.

This oscillation is the enemy of movement.

When the soil thaws, vehicles churn it into deep, sucking mud. Tracks carve channels that fill with slush. Roads begin to collapse at their edges, asphalt giving way to brown slurry. Then the temperature drops again, and the churned mud freezes into jagged, concrete hard ridges that shatter wheels, twist axles, and immobilise armour.

The ground becomes neither passable nor stable. It is simply hostile.

Off road movement becomes a gamble. Leave the asphalt and you sink. Stay on it and you become predictable, observed, mapped, targeted. Recovery operations, once routine, turn into death traps under aerial surveillance.

Russian soldiers describe the terrain as something almost sentient, a force that punishes haste. Once a vehicle bogs down, it rarely moves again. Crews strip optics, radios, batteries, sometimes entire subassemblies, and leave the carcass where it stands. A stuck machine becomes a fixed point for artillery or loitering munitions.

Fields, roadsides, and tree lines fill with these remnants. Trucks nose down in frozen ruts, armoured vehicles tilted at unnatural angles, tanks half submerged where someone tried to force them through soft ground and failed.

Zaporizhzhia pressure along the marsh

South of Zaporizhzhia city, the land flattens into exposed fields and industrial sprawl. Along the Dnipro, what was once a broad reservoir has become a wide belt of marsh. Stagnant water, reeds, broken banks, sludge that will not support weight. Vehicles sink almost immediately. Infantry moves only along narrow margins.

No serious attempt is made to cross it.

Instead, Russian units edge along its rim, advancing north through Huliaipole and surrounding villages, straightening the line, collapsing Ukrainian positions that once relied on open ground for defence. These positions held for years. Once flanked, they emptied quickly.

Counterattacks still come. They follow a familiar pattern.

Ukrainian infantry moves out across bare winter fields, sometimes under cover of fog. The fog allows them to start. Then it thins, or the wind shifts, or the rain stops and drones return. FPVs descend. Artillery follows within minutes.

When Russian infantry advances afterward, they encounter the aftermath. Bodies in the open, often in small clusters, sometimes alone. Many never reached cover. Some lie face down, weapons still slung. Others sit frozen against shallow berms, as if resting.

In winter, the dead do not disappear. The cold preserves them. Uniforms stiffen. Faces grey. The metallic tang of blood mixes with frozen earth. Some are buried quickly. Some are marked. Many are left.

It is not cruelty. It is time and arithmetic.

Russian units now operate inside the outer suburban belt of Zaporizhzhia. Warehouses, low apartment blocks, factory yards, feeder roads. The city itself remains largely intact not because it is strong, but because it is being deprived. A city that cannot be supplied does not need to be stormed.

Fog rain and silence

Fog changes everything.

When it descends thick enough, sometimes reducing visibility to a few metres, drones stop flying. They cannot see. They cannot orient. FPVs crash or refuse to launch. Reconnaissance UAVs land or drift uselessly.

Rain does the same. So does freezing drizzle. Strong gusting wind grounds even experienced operators.

These are the moments Russian units wait for.

When the drones fall silent, infantry moves. Slowly. Deliberately. Storm groups are small. Two or three men, spaced out, moving by hand signals and memory rather than radios. They close distances that would be suicidal under clear skies, stepping over frozen ruts, listening for the crunch of boots or the faint hum that signals a drone has somehow stayed airborne.

The battlefield in fog is eerie. Sound is muffled. Shelling feels distant even when it is close. The air smells of damp concrete, cordite, and diesel. Men wait for hours in observation posts, cold seeping into bones, breath fogging inside scarves.

When the fog lifts, movement stops. Positions are dug in. Fields of fire are established. The waiting begins again.

Kostiantynivka the knot tightens

If Zaporizhzhia is pressure, Kostiantynivka is geometry.

Roads and rail lines converge here, feeding Druzhkivka, Kramatorsk, and Sloviansk. Lose Kostiantynivka, and the entire northern Donetsk defence begins to starve.

Pressure now comes from three sides.

From the south, Russian infantry advances through ruined villages, moving through gardens, garages, factory yards. From the east, they work along rail corridors and industrial ruins. From the north east, they press down through smaller settlements, threatening the last viable supply routes.

Inside Kostiantynivka, Ukrainian positions grow brittle. Ammunition is rationed. Rotations slow. Evacuation under drone threat becomes sporadic. Wounded men often remain in basements for days, sometimes dying there in the cold.

Russian storm groups entering the outskirts describe buildings where no one fires back. Not because defenders fled, but because they are already dead. In some positions, rifles are stacked neatly, as if waiting for orders that never came.

The city is not collapsing in a rush. It is emptying under pressure.

Who is left to defend

Across the front, Russian units increasingly encounter the same defenders.

They are older men, often in their forties or fifties. Equipment is mismatched. Boots are worn. Training is minimal, visible in how they react to fire. When drones appear, many freeze or scatter blindly.

Surrender happens, but rarely. Fear and disorganisation overwhelm instinct. When it does occur, it is usually after isolation. A man alone in a basement, out of ammunition, having watched everyone else die.

More often, positions are simply overrun. Trenches are entered to find bodies slumped against walls, rifles still loaded. Some died days earlier. Others moments before.

This pattern repeats along the entire front.

Tracks weight and broken machines

Winter exposes equipment differences brutally.

Russian armoured vehicles use wider tracks, distributing weight more effectively. They still bog down. Winter spares no one. But less often, and recovery is more feasible.

Western supplied Ukrainian vehicles fare worse. Many are heavier, with narrower tracks or wheels, designed for roads, not churned steppe. In thawing ground, they sink quickly.

Russian soldiers repeatedly encounter Ukrainian vehicles that were not destroyed but systematically cannibalised. Optics removed. Radios gone. Batteries stripped. Sometimes even engine components missing. Fuel tanks are empty.

These machines were abandoned not in battle, but by logistics.

Logistics collapsing inward

Winter is merciless to supply systems.

Ukrainian units operate a patchwork force. Different tanks, infantry vehicles, artillery systems. All requiring different spare parts, tools, fluids, and training. There is no unified maintenance chain.

When something breaks, it often stays broken.

Crews cannibalise one vehicle to keep another moving. Eventually, there is nothing left to cannibalise. Fuel shortages compound everything. Generators go silent. Heaters shut down. Vehicles are abandoned not because they are damaged, but because there is no diesel to move them.

Russian soldiers advancing through former Ukrainian positions find workshops full of half dismantled machines, parts laid out neatly, then simply left behind. Someone tried to fix them. Time ran out.

Chasiv Yar Lyman and the road north

West of Chasiv Yar, the terrain rises slightly. Enough to matter. Months of fighting have reduced the town to layered rubble. What remains are firing points embedded in concrete and earth.

Beyond lies Kramatorsk, but no one rushes toward it. The city behind the city must fall first.

North toward Lyman and along the Siverskyi Donets, forests thin in winter. Vehicles slide into ditches. Infantry moves on foot through frozen mud. Supplies are carried by hand where trucks once went.

Along the road to Sloviansk, Russian patrols find Ukrainian dead killed while attempting resupply. Ammunition boxes abandoned mid carry, stretchers unused, ration packs scattered in frost.

The goal is not to storm Sloviansk. It is to kill the road.

A road under constant drone and artillery threat eventually stops functioning. When it stops, so does the defence it feeds.

Attrition by arithmetic

Across the entire front, from Zaporizhzhia through Kostiantynivka, Chasiv Yar, and up toward Lyman, the numbers are relentless.

Each day, Ukrainian forces lose roughly a brigade’s worth of dead and permanently wounded across the front. Not abstract estimates, but men counted in trenches and hospitals.

Over sixty or seventy days, this becomes catastrophic. Entire units vanish. Replacements arrive older, less trained, more fearful. Veterans desert when they can. Others fight until they are killed or crippled.

Russian soldiers notice the difference immediately.

New defenders fire wildly. They fail to coordinate. They abandon positions sooner. They die faster.

This is not collapse. Not yet.

It is structural failure unfolding in slow motion.

Russian losses and restraint

This war is not cost free.

Russian units take casualties. Drones strike. Artillery lands. Men freeze in observation posts. Vehicles bog down.

But organisation holds. Units rotate. Supplies arrive. Positions are consolidated before advancing. There is no rush to plant flags on ruins.

The war is treated as labour.

When the fog returns

Fog rolls in again. Rain follows. Wind rises. Drones land.

Somewhere outside Zaporizhzhia, a small group moves forward, boots sinking into thawed earth, rifles held low. Somewhere near Kostiantynivka, another building is entered and found silent. Somewhere on the road to Sloviansk, another vehicle is abandoned.

This is the war now.

Not fast. Not loud.

But patient, methodical, and unforgiving.

When spring comes, the ground will harden. Movement will increase. But the shape of the front will already have been decided by what happened quietly, relentlessly, and mercilessly in winter, when the fog came down and the drones fell silent.