Everything Here Follows the Rent

Companion piece: Read this alongside The Language the City Forgot, a first hand account of how Yiddish organises daily life in South Williamsburg.

Williamsburg Is Not a Theme Park. It Is a Home.

I will choose one topic because it is the lever behind the rest: housing pressure and gentrification, and the way it drags everything else into the street with it.

I have lived in Williamsburg long enough to remember when outsiders did not come here to discover it. They came here for something else. Some came for cheap rent, some came for a picture, some came for a feeling. Many were polite. Some were kind. But the pattern was the same. They arrived in waves, and with each wave the ground under our feet shifted.

People outside our world talk about gentrification as a moral story with heroes and villains. They want a clean script. They do not understand that for us it is not a trend, it is a pressure system. It tightens slowly, then suddenly. A landlord sells. A building changes hands. An apartment that held a family becomes a unit. A unit becomes an asset. An asset becomes a weapon. And then one day you wake up and realise that the neighbourhood has been priced not merely above your means, but above your right to remain.

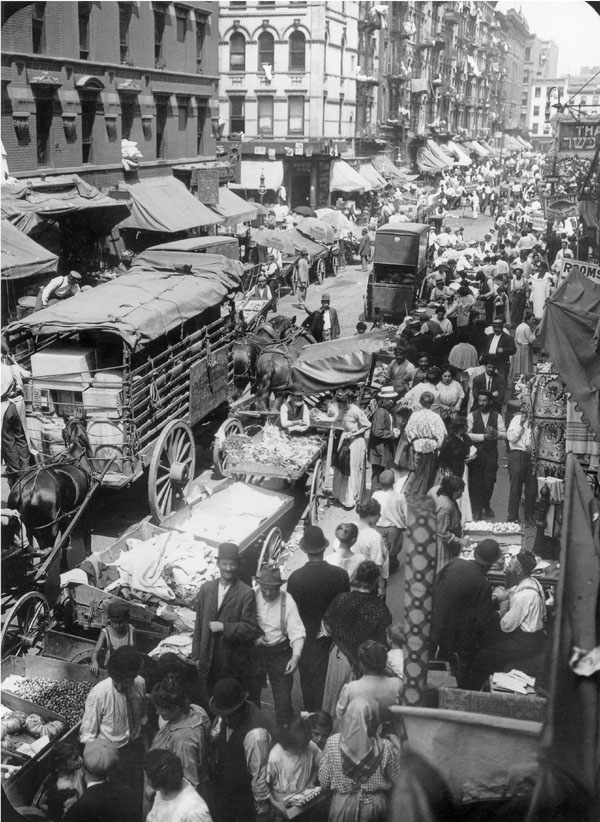

You cannot understand Williamsburg life without understanding that the street is not just a street. It is an extension of the home, the school, the synagogue, the family. When the street changes, we feel it in the most intimate places. It is not only about money. It is about whether a community can remain legible to itself.

I have read the community papers for years. You learn quickly that they are not neutral. They are not pretending to be. They are inside the fight, and they speak to an audience that already knows the map. When those papers describe the newcomers as a cultural force, even as a threat, it is easy for outsiders to laugh, or to sneer, or to call it paranoia. But that reaction is a luxury. The papers are describing something real: the erosion of control over space. People call it change. We call it: we are being pushed.

And here is what outsiders miss. The pressure does not land evenly. It does not land on the community in the abstract. It lands on specific households. The young couple with a new baby. The family with seven children squeezed into rooms that were never designed for seven children. The grandfather who has lived on the same block for decades and now has to climb stairs because the building maintenance has become a negotiation. The women who are doing the arithmetic every week, stretching food, stretching rent, stretching dignity.

This is where poverty enters the story, not as a slogan, but as a reality. People imagine Williamsburg and they imagine a uniform world. They do not see the internal inequality. They do not see that a neighbourhood can look stable on the surface while many families are one rent rise away from crisis. When housing is scarce, every extra child, every illness, every job wobble becomes a threat multiplier. You do not need ideology to explain fear. You only need a rent letter.

Now add schooling.

To outsiders, the schooling dispute is simple. It is standards. It is basic education. They say the state has a duty, and they are not wrong that the state believes it has one. To us, it is experienced as intrusion into the engine room of identity. The school is not only a place of learning. It is where a child is shaped, trained, taught how to walk in the world without dissolving into it. When enforcement intensifies, it does not feel like a policy debate. It feels like the city has decided it can enter the house through the classroom door.

And here is the part that makes everything worse: the housing pressure makes the schooling conflict sharper. When families are already squeezed, any threat to schools becomes not just an ideological threat but a logistical threat. If parents are told to move children, if funding becomes uncertain, if oversight becomes punitive, it hits a community already stretched by rent. The pressures stack. That is how stability becomes brittle.

Then there is factional politics, which outsiders love to sensationalise. They will say our papers are propaganda, that everything is controlled, that nothing is free. The truth is messier. There are internal lines and loyalties, yes. There are rivalries, yes. There is power, yes. But those internal disputes exist inside a larger shared fear: losing the neighbourhood as a usable home. Whatever people fight about internally, most of them understand that if Williamsburg becomes unaffordable, the argument is over because the community itself will be scattered.

Let me say something that will upset both sides, because it is true.

To the gentrifiers, the ones who tell themselves they are only living their lives: you are not neutral. Your presence has consequences. Even if you are polite, even if you mean well, your housing demand changes the market and your culture changes the street. You can call that unfair, but it is still real.

To my own community, to those who speak as if the outside world has no rights at all: we live in a city. We benefit from its infrastructure, its protection, its economy. We cannot speak as if we are a state within a state and expect no friction. That is fantasy. The hard work is to defend our way of life without pretending we can abolish the city around us.

So what do I want?

I want the city to treat this neighbourhood as a living community, not a blank canvas for capital. I want housing policy that recognises family density, not just studio demand. I want enforcement that distinguishes between genuine harm and cultural difference. I want schools to be debated with seriousness, not weaponised with contempt. I want the press, our press, to speak strongly but also wisely, because language can harden hearts faster than any rezoning map.

Most of all, I want outsiders to stop treating Williamsburg like a story they get to narrate. It is not a backdrop. It is not a brand. It is not a weekend. It is a home.

And when a home is under pressure, people do not become more tolerant. They become more defensive. That is not because they are evil. It is because they are human.

If you want peace here, start with the material truth: who can afford to stay. Everything else, culture, schooling, politics, even the tone of the newspapers, follows the rent.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

- The Language the City Forgot — A first hand account of how Yiddish still organises the street in South Williamsburg.

- Yiddish New York: A Living Heritage of Torah, Safety, and Continuity — How language and institutions turn memory into continuity in New York.

- Ashkenazi Ethics and the Burden of Conscience — A moral tradition shaped under pressure, and what it asks of community life.

- Tikkun Olam: The Jewish Call to Repair the World — Repair as practical responsibility, grounded in limits rather than display.

- Yom Kippur Sermon: Peace Amid Ashes — A call for moral discipline under fear, without surrendering compassion. i

- Hanukkah and the Covenant of Light — Why Jewish continuity is a public act, not nostalgia.

- Why Jewish Humour Is Not Self-Deprecation — Humour as inner sovereignty, and as restraint against certainty.

- Fifth Floor, Christmas Day — A winter essay on housing and poverty, and what pressure does to dignity.

- The Year the World Stopped Pretending — An editorial on institutional credibility, pressure, and the stories we tell ourselves.

- About telegraph.com — What Telegraph Online is, and what it is not.

References

- Telegraph Online: The Language the City Forgot — Companion reporting on Yiddish as a daily civic language in South Williamsburg.

- Telegraph Online: Yiddish New York — Context on New York’s Yiddish ecosystem and continuity infrastructure.

- Telegraph Online: Why Jewish Humour Is Not Self-Deprecation — A related essay on pressure, identity, and social defence mechanisms.

- Telegraph Online: Ashkenazi Ethics and the Burden of Conscience — Ethical framing for community cohesion under strain.

You Tube embedded video under licence, Williamsburg