AI Is Raising Productivity. Britain’s Economy Is Absorbing the Gains

This article builds on an earlier analysis of why AI driven productivity gains do not automatically translate into higher living standards. That piece examined the emerging productivity effects of AI itself. This follow up looks at the structural mechanisms that determine where those gains actually go in Britain’s economy. Read the earlier article here.

Artificial intelligence is already raising output per hour in specific tasks, but higher productivity does not automatically translate into higher wages or lower prices. In Britain, that link has been weak for decades. This piece explains why AI enhanced productivity flows through Britains existing economic structure without delivering broad prosperity.

What productivity means

When this article refers to productivity, it means output per hour worked. This is the standard measure used by official statisticians and international comparisons, and it is the one most directly connected to living standards. Output per hour captures how much value an economy produces for a given amount of labour time. It avoids the ambiguities of residual measures and allows comparison across sectors and countries. This definition is not rhetorical. It is the benchmark against which claims about growth, efficiency, and prosperity are judged.

Higher productivity increases the amount of output an economy can generate from the same number of working hours. That creates surplus. What it does not do is determine where that surplus goes. Productivity does not automatically raise wages, lower prices, or improve public services. Those outcomes depend on how gains are transmitted through wages, prices, investment, and costs. Treating productivity as synonymous with prosperity is a category error. Productivity measures capacity. Prosperity reflects how that capacity is distributed and experienced.

Britains productivity problem is not disputed. For more than a decade, output per hour has grown slowly by historical and international standards. This productivity puzzle is widely recognised across institutions and political cycles. The disagreement is not over whether the problem exists, but over why productivity gains, when they occur, have not reliably translated into higher wages and broader improvements in living standards. That question of transmission is where the analysis begins.

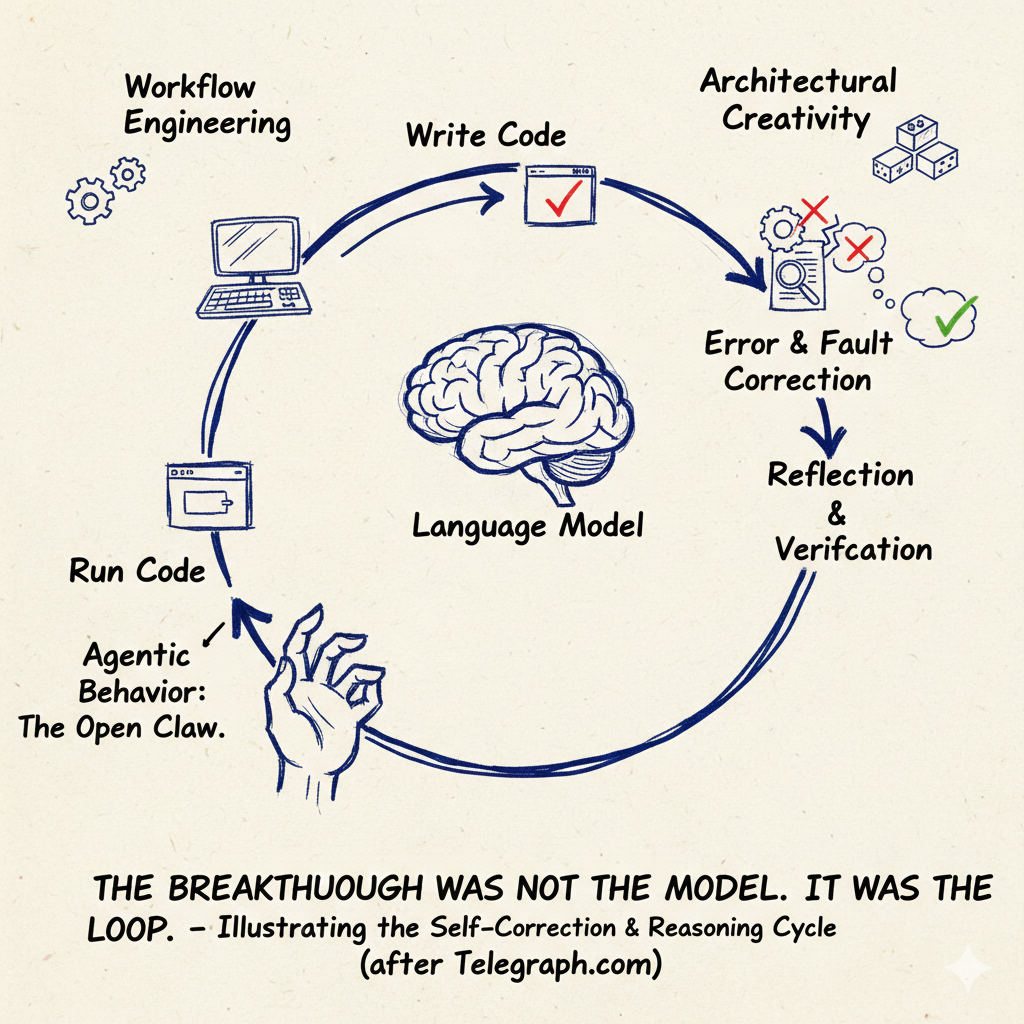

AI raises output per hour at the task level

Artificial intelligence systems are already raising productivity in a limited but measurable sense. They increase output per hour worked in specific white collar tasks. This effect is not economy wide and does not apply uniformly across sectors. It is concentrated in activities such as drafting, coding, analysis, document review, customer support, and administrative work. In these contexts, workers assisted by AI tools are able to complete more tasks, or complete the same tasks faster, within the same working hours.

The mechanism is straightforward. AI systems reduce the time required for searching, summarising, drafting, and error checking. They compress cognitive overhead rather than replace labour outright. The result is not the elimination of roles, but higher task throughput per hour worked. These gains are incremental, but they are observable and repeatable across similar tasks.

Controlled studies and field experiments consistently show this pattern. Workers using AI assistance complete tasks more quickly and, in many cases, with equal or improved quality. The gains vary by task and skill level and are strongest where work is text heavy or structured. Importantly, these findings measure time saved per task or output per hour, not wage growth, firm profitability, or aggregate output. They establish productivity in its narrow, technical sense, and nothing more.

These task level gains do not, by themselves, imply higher wages, lower prices, or faster economic growth. They show that AI raises productive capacity at the margin, within defined bounds. Whether that capacity translates beyond the task depends on how gains are absorbed, transmitted, or offset elsewhere in the economy.

Productivity is not prosperity

Productivity measures how much output is produced for a given amount of labour time. Prosperity describes how people experience the economy through wages, prices, public services, and living standards. The two are related, but they are not the same. Productivity creates potential. Prosperity depends on transmission.

In Britain, the link between productivity and typical earnings weakened long before the emergence of artificial intelligence. Over recent decades, periods of rising output per hour have not reliably translated into sustained growth in real wages for most workers. This divergence is well documented and has persisted across economic cycles. It reflects a structural change in how productivity gains move through the economy rather than a temporary shock.

The weakening of this link appears in two places. Productivity gains at the firm or task level do not consistently appear in pay packets. Nor do they reliably reduce the prices households face for essential goods and services. Higher output per hour can coexist with stagnant wages and rising costs when transmission channels are weak or interrupted.

Once productivity and prosperity are separated in this way, the central question becomes unavoidable. If productivity gains exist but outcomes do not improve, where does the surplus go?

Where gains get stuck in Britain

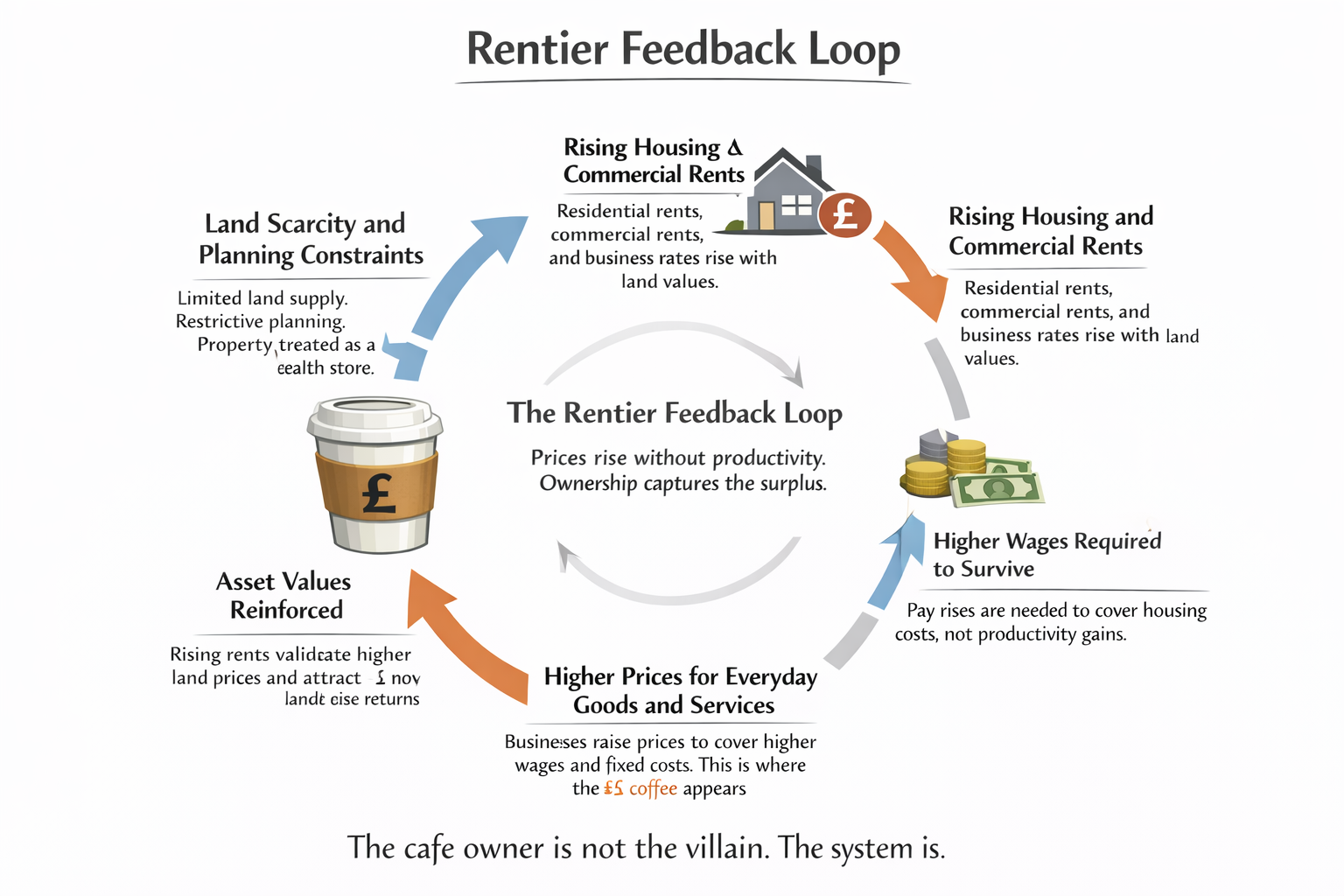

If productivity gains do not translate into higher wages or lower prices, the explanation lies in structure rather than measurement. Economies contain bottlenecks where gains are absorbed before they can spread. In Britain, these bottlenecks are persistent and concentrated in sectors where supply adjusts slowly and pricing power is strong.

The most significant of these is land and housing. In Britain, increases in income or productive capacity tend to capitalise rapidly into higher land values and housing costs. When supply is constrained, higher ability to pay leads not to more homes at scale, but to higher prices for access to existing stock. Gains that might otherwise support consumption or investment are absorbed by housing costs instead.

A similar dynamic operates in commercial property. Many firms face high and inflexible occupancy costs that adjust independently of productivity improvements. Where output per worker rises, margins may improve temporarily, but those gains are often offset by higher rents and fixed charges. Because these costs are tied to scarcity rather than output, productivity improvements do not reliably translate into expansion or lower prices.

Infrastructure costs form another bottleneck. Energy, transport, and other network services are priced through regulation and long investment cycles. Productivity gains in one part of the economy do not automatically reduce these costs elsewhere. They are experienced as fixed or administered charges that absorb purchasing power regardless of efficiency improvements upstream.

Capital allocation reinforces these effects. A large share of investment flows toward existing assets rather than new productive capacity. When productivity gains raise returns in certain activities, capital does not necessarily expand output across the economy. Instead, returns are often reflected in higher asset valuations.

Finally, gains face barriers to diffusion. Differences between high productivity and low productivity firms persist over long periods. Where scaling is slow and diffusion weak, improvements remain concentrated rather than economy wide. Productivity gains exist, but they do not reliably travel.

How AI flows through chokepoints

Artificial intelligence does not enter a neutral economic landscape. It operates within existing constraints. Where bottlenecks already exist, AI enhanced output per hour passes through them rather than bypassing them. The effect is not to overturn existing patterns of allocation, but to move more quickly along them.

When AI raises output per hour at the task level, firms can generate more value with the same labour input. In the short term, margins may improve. However, many firms operate with high fixed costs that are relatively insensitive to productivity gains. Occupancy costs, energy charges, and overheads absorb gains before they can support expansion or be passed on through wages or prices.

Productivity improvements can also change what firms are able to pay for scarce resources. Where space is limited and demand is strong, higher output per worker increases tolerance for higher rents rather than lowering prices for consumers. Gains are capitalised into costs tied to scarcity rather than production.

AI driven productivity gains do not require reductions in working hours to have an effect. Output per hour can rise while hours worked remain unchanged. The surplus created accrues initially at the firm level. Without strong transmission mechanisms, it does not automatically appear in wages.

Capital responds unevenly. Where gains are concentrated, capital may bid up the value of positions rather than fund broad expansion. Productivity improvements alter relative returns without resolving the constraints that limit scaling and diffusion.

Why this outcome is not inevitable

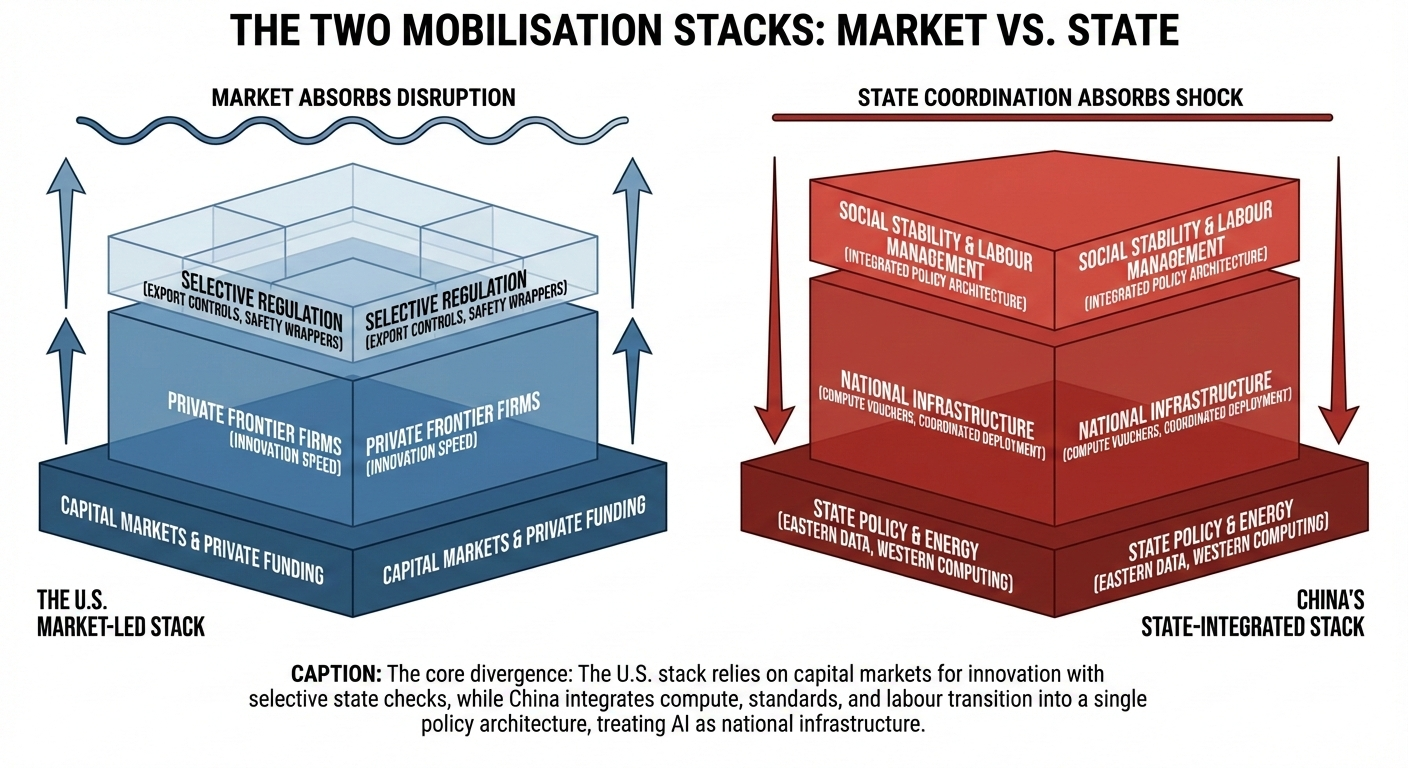

This pattern is not universal. Different systems translate productivity gains into wages, prices, and investment with varying degrees of success. The difference lies in institutional conditions, not in technology itself.

Housing supply illustrates this clearly. Where supply responds readily to demand, higher incomes do not translate directly into higher housing costs. Where supply adjusts slowly, the opposite occurs. Productivity gains raise the ability to pay, and prices rise accordingly.

Investment patterns matter as well. In systems with higher investment intensity, productivity gains are embodied in new capital and capacity. Where investment is persistently weak, gains improve returns without materially expanding production.

Diffusion is the final distinction. Where productivity gains spread quickly beyond leading firms, average performance rises. Where diffusion is slow, gains remain narrow. Aggregate outcomes stagnate even as technology improves.

Three conceptual charts

The diagrams below are conceptual illustrations. They are directional only and should not be interpreted literally as statistical series or forecasts.

Chart 1. Conceptual illustration of task level productivity gains. Directional only. Not a statistical series.

Chart 2. Conceptual illustration of surplus allocation pathways. Directional only. Not a statistical series.

Chart 3. Conceptual feedback loop showing how gains can be absorbed when constraints persist. Directional only. Not a statistical series.

The strongest opposing argument

A serious objection begins with a familiar principle. If productivity rises, competition should eventually force prices down, wages up, and investment higher. Excess profits should be eroded, and gains shared more broadly over time.

This argument holds where supply is elastic and competition is strong. Under those conditions, productivity gains often do improve outcomes.

The difficulty arises when those conditions do not hold. Where access to housing, space, or infrastructure is constrained, competition does not dissolve costs in the usual way. Higher productive capacity raises the ability to pay for scarce resources, and prices adjust upward instead.

Time alone does not resolve this. The constraints that limit supply responsiveness and weaken transmission have persisted across economic cycles. Productivity gains have not, in practice, corrected them. This suggests that the failure of translation is structural rather than transitional.

What raising productivity would require

Once productivity is separated from outcomes, the meaning of raising productivity changes. It is no longer enough to point to technological improvements. A set of underlying conditions must be present for gains to translate into higher living standards.

Supply must respond when demand rises. Without that, gains are capitalised into prices.

Investment must deepen capacity rather than revalue assets. Without that, output does not expand.

Gains must diffuse beyond leading firms. Without that, aggregate performance stagnates.

Finally, gains must transmit through wages or prices. Without that, productivity improvements accumulate without improving lived outcomes.

Conclusion

Productivity measures capacity, not experience. Artificial intelligence already raises output per hour in bounded and observable ways. Yet productivity does not determine outcomes on its own. In Britain, transmission has been weak for decades. Gains exist, but they do not reliably travel.

AI does not alter this by itself. It enters an economy shaped by constrained supply, weak diffusion, limited capital deepening, and fragile transmission to wages and prices. Within such a system, higher output per hour increases capacity without materially changing experience. Until those structural conditions change, AI will continue to raise productivity on paper while living standards remain largely unchanged, not because the technology has failed, but because the systems existing incentives determine where the gains tend to go.

Related analysis: This article builds on an earlier piece examining how artificial intelligence is already raising productivity at the task level. That article focused on the technology itself and the evidence for higher output per hour. The analysis above takes the next step, explaining why those gains do not automatically translate into higher living standards in Britain, and how the structure of the economy determines where productivity gains end up.

Read the earlier article: AI Is Raising Productivity. That Is Not the Same Thing as Raising Prosperity.

References and sources

UK Office for National Statistics. Labour productivity and output per hour definitions and long run productivity data for the UK economy.

OECD. Productivity statistics and international comparisons of output per hour worked across advanced economies.

National Bureau of Economic Research. Studies on generative AI and task level productivity, including field experiments measuring time saved and output quality.

Stanford University and MIT affiliated research. Experimental evidence on AI assisted knowledge work and heterogeneous productivity effects across workers and tasks.

Bank of England. Analysis and speeches on weak investment, capital deepening, and the transmission of productivity gains in the UK economy.

UK Competition and Markets Authority. Reports on market power, pricing behaviour, and structural constraints in housing, energy, and infrastructure markets.

More on Economics:

This article forms part of Telegraph Online’s Economics coverage, examining productivity, growth, capital allocation, and living standards. You can read further analysis on these themes in the Economics section on Telegraph.com.

Browse the Economics section on Telegraph.com