Two Classrooms, Two Narratives. Why Britain and China Do Not Hear Each Other

When British officials travel to China, the assumption in London is often that the meaning of the visit is obvious. Engagement signals responsibility. Dialogue signals stability. Presence signals relevance. In Beijing, the same visit can be read very differently. This essay explains why and why Britain keeps being surprised by the reaction.

On paper, a diplomatic visit is a small thing. A few meetings. Carefully chosen language. Photographs taken at a respectful distance. In London, these moments are usually described as reassurance, proof that Britain is still present, still engaged, still heard.

That pattern has repeated during recent ministerial visits and naval transits, each framed domestically as routine engagement and received in Beijing as strategic signalling.

In Beijing, such visits are often heard another way. As alignment. As signalling. As a reminder that Western powers still approach China with habits formed in an earlier era.

The difference is not about tone, tact, or the personality of the visitor. It is about history. Specifically, which history is taught, which history is reinforced, and which history is quietly omitted.

Britain and China do not merely disagree about the present. They have been trained to see the world through different pasts.

Two Ways Of Learning Power

To understand why the same action produces such different reactions, it helps to imagine two classrooms.

In one, history is taught as continuity. In the other, history is taught as inheritance.

That distinction shapes almost everything that follows.

What Chinese Students Grow Up Knowing

Chinese students are introduced early to the idea of civilisational continuity. History is not a series of disconnected episodes. It is a long story of order, disruption, and recovery.

The disruption matters most.

Modern Chinese education focuses on a period when foreign powers took advantage of weakness. Students learn how law, trade, and force were used together to impose outcomes China did not choose. Britain is not an abstract presence in this story. It is named, dated, and placed.

The lesson is not taught as grievance. It is taught as warning. When a state loses power, it loses agency. Moral language does not prevent that. Strength does.

What Chinese students are taught about Britain

That Britain forced the importation of opium into China despite imperial bans, and used naval force when resistance hardened. That unequal treaties stripped China of tariff and legal autonomy. That the destruction of the Old Summer Palace was a punitive act meant to demonstrate dominance. That Hong Kong was taken under conditions China could not refuse.

This education produces a population that reads foreign military and diplomatic activity as signalling. When Western warships appear near Chinese coasts, they are not heard as routine. They are heard as pressure shaped by memory.

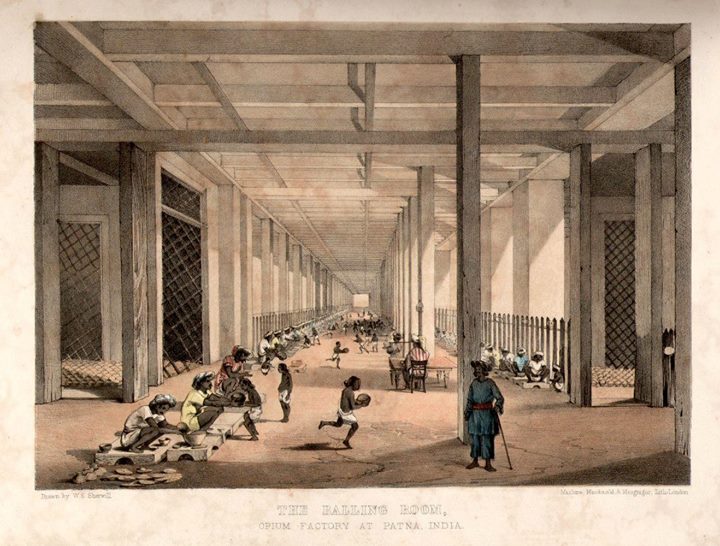

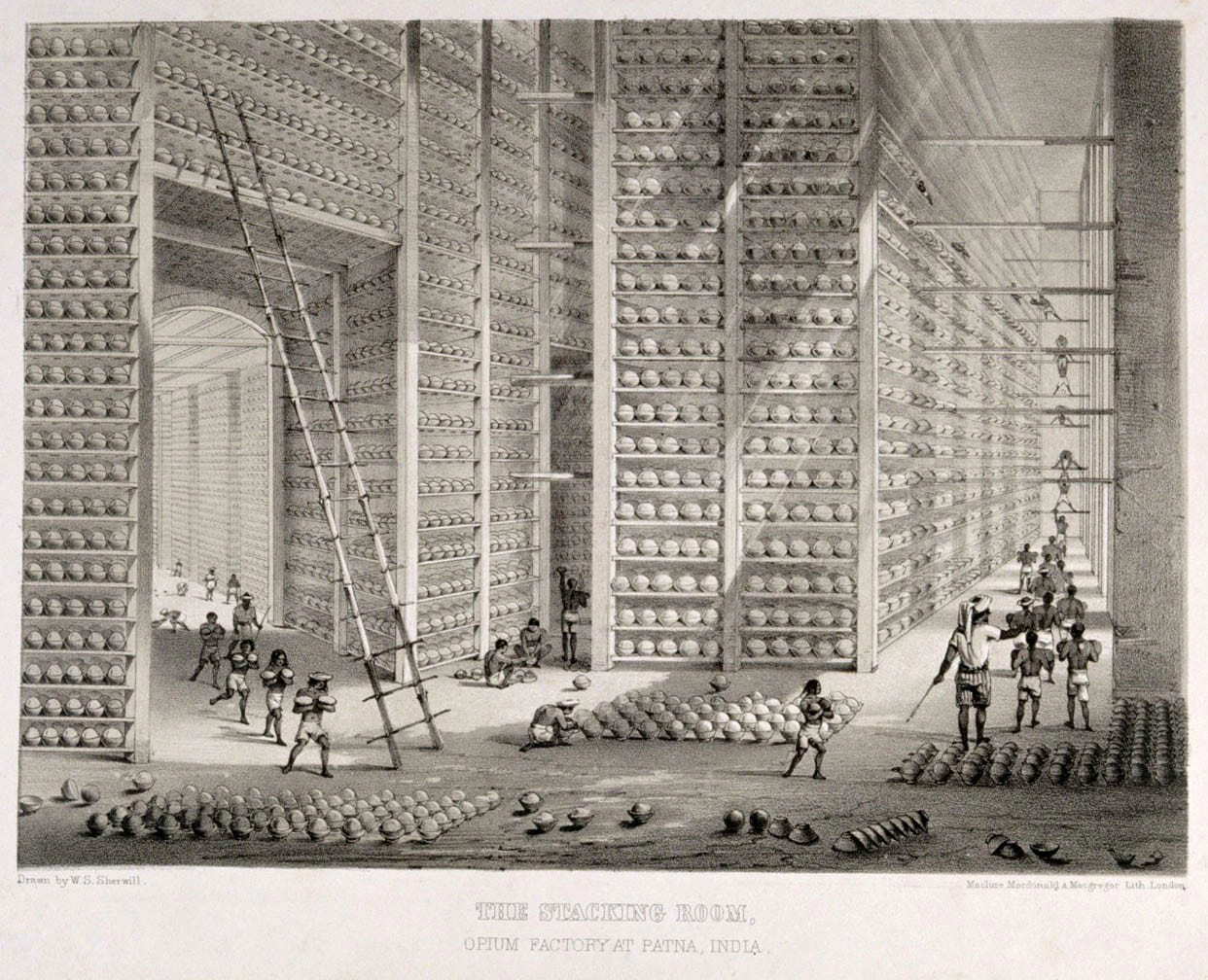

Illustrations from the nineteenth century show opium processing facilities of the kind that operated across British ruled India. Thousands of acres were converted to opium cultivation, feeding factories like these so the drug could be exported into China. When the Qing emperor banned the trade and objected to narcotics entering Chinese territory, Britain responded with gunboat diplomacy, forcing opium imports on China at scale. The trade enriched Britain while spreading addiction across Chinese society.

What British Students Are Rarely Shown

British education tells a different story.

History is taught primarily as an internal narrative. Monarchy. Parliament. Industrialisation. War. Empire appears, but often as administration rather than coercion, presence rather than domination.

In recent years, some classrooms have begun to address imperial history more critically, but this remains uneven and peripheral rather than foundational.

What is still largely missing is how Britain was experienced by those it ruled.

Colonial realities seldom central to British classrooms

Episodes such as Jallianwala Bagh, where lethal force was used against unarmed civilians. The economic reshaping of India under colonial rule, including deindustrialisation and extraction. The condition in which Britain left India, marked by widespread illiteracy and malnutrition. Britain’s role in China’s century of humiliation narrative.

The result is not ignorance of dates, but absence of perspective. British students grow up knowing what Britain did for itself, but not how Britain is remembered elsewhere.

That gap becomes visible later, when Britain expects to be heard as a neutral actor and is received as something else.

When The News Becomes The Lesson

Where education leaves gaps, media steps in.

For decades, British news coverage has reinforced a sense of Britain as a principal actor aligned with American power and speaking in the language of shared values. Alignment is presented as judgement. Dependence as leadership.

This is not the result of a single editorial line. It is the effect of structure. Access, briefings, and proximity reward repetition of official assumptions. Over time, a coherent worldview forms, one that rarely pauses to ask how Britain is being read outside its own echo.

The Taiwan Strait Test

Nowhere is the gap clearer than Taiwan.

Chinese students are taught that Taiwan is part of China and that foreign military activity in the Taiwan Strait is an intrusion into core sovereignty. British audiences are rarely taught this context.

So when British warships transit the strait, the act is described at home as routine navigation. In Beijing, it is read as alignment and pressure.

If Chinese warships regularly operated between Britain and Ireland, or repeatedly transited the English Channel while issuing statements about routine navigation, Britain would not treat it as routine. China applies the same logic to Britain’s actions near its coast. Britain rarely applies it to itself.

Why the same act sounds different in Beijing

Because it occurs near China’s coastline. Because it aligns with American strategic signalling. Because it sits within a long memory of foreign coercion. Because it is heard as a test of hierarchy, not a technical exercise.

The Shock That Followed

Britain’s unease did not begin with a change in American policy. It was exposed by it.

For decades, British elites assumed American backing was permanent. When that assumption cracked, the reaction felt like abandonment. In reality, it was recognition delayed.

Britain had never fully explained to itself what it was without American amplification.

A Choice Still To Be Made

Britain cannot return to a role that depended first on empire and then on American scale.

It can act as a convenor. It can specialise. It can align honestly. In practical terms, that means fewer symbolic gestures of power and more visible investment in areas where Britain still carries credibility, from standards setting to climate coordination.

The world is not confused about Britain’s position. Britain is.

Until British classrooms, media, and diplomacy align with reality rather than habit, Britain will keep mistaking reassurance for influence and surprise for hostility.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

Europe Without a Guarantor Why Britain Is Reopening the China Question

An examination of how Britain’s China policy is shifting as American guarantees become less certain and strategic autonomy returns to the agenda.

The Chinese Embassy Panic Is a Legal Failure Not a Security One

A legal analysis of the London embassy controversy, arguing that political fear has displaced statutory process and proportionality.

Xi Jinping Corruption and the Chain of Command Inside China’s PLA

A detailed look at how authority, discipline, and loyalty function inside China’s military and why command coherence matters more than hardware.

China’s Quiet Doctrine After the Venezuela Raid

How Beijing responded to an extraterritorial seizure not with spectacle but with law, doctrine, and long-term positioning.

The Politics Behind the China Embassy Scare

An investigation into how speculation around the Chinese embassy became a proxy for Britain’s unresolved anxieties about power and decline.

Custody Without Protection How Canada Learned the Limits of Alignment

A case study in how enforcing American power does not guarantee American protection, with implications for other allied states.

Luohe and the Escort Screen That Turns China’s Carriers Into Real Power

An explanation of why China’s naval strength lies in systems and escorts rather than headline platforms.

How the China Embassy Debate Reveals Britain’s Strategic Confusion

A closer look at how domestic politics and media framing distort Britain’s understanding of China and itself.

Research and intellectual sources

Colonial history and imperial political economy

Shashi Tharoor on the economic consequences of British rule in India. Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik on colonial extraction, deindustrialisation, and the drain of wealth. Romila Thapar on historiography and how empires narrate themselves. Amiya Kumar Bagchi on colonial capitalism and underdevelopment. Basil Davidson on the administrative violence of empire. Adam Hochschild on coercion, punishment, and moral blindness in imperial systems.

China, historical memory, and nationalism

Chinese official history curricula on the Opium Wars and the century of humiliation. Rana Mitter on modern Chinese nationalism and historical memory. Odd Arne Westad on China’s encounters with Western power. James Millward on empire, coercion, and frontier governance in Chinese history.

British foreign policy and post imperial identity

UnHerd essays on Britain as a junior partner in an American led system. Declassified UK reporting on media, intelligence, and security alignment. UK parliamentary briefings on China policy, naval deployments, and the Taiwan Strait. Academic literature on post imperial identity and strategic overstretch.

Media systems and narrative formation

Chris Hedges on media, power, and elite consensus. Glenn Greenwald and Matt Taibbi on access journalism and narrative discipline. Comparative media studies on agenda setting and omission as political force.

Geopolitics and strategic signalling

John Mearsheimer on great power politics and security dilemmas. Gilbert Doctorow and Alexander Mercouris on naval signalling and alliance behaviour. Jeffrey Sachs on multipolarity and the erosion of assumed Western leadership.

Telegraph Online reporting and analysis

Original reporting and analysis on China, Britain, naval signalling, alliance dependency, and strategic recalibration published on Telegraph.com.