Sadiq Khan Warns of Mass Unemployment. AI Poses a Deeper Threat to London

London is not heading for mass unemployment. It is heading for something quieter and more destabilising: the erosion of its middle class. Artificial intelligence will not empty offices or shutter cafés. It will compress the city’s class structure preserving service work, concentrating elite professional power, and dismantling the career ladders that once carried people into the middle. The result will be falling purchasing power, weaker demand, and a city that continues to function while becoming narrower, more brittle, and harder to enter.

This article was prompted by a warning that will be delivered later this week. In his Mansion House speech, Sadiq Khan is expected to argue that artificial intelligence could bring about “mass unemployment” in London unless ministers act. The anxiety is real. The conclusion is wrong.

London’s problem is not that work is disappearing. It is that the ladder that once led into the middle class is being quietly dismantled. What follows is an attempt to explain how that happens, why London is unusually exposed, and why this form of economic damage is more dangerous than the headline panic it replaces.

Why London feels the pressure first

London’s exposure to artificial intelligence is structural, not accidental. The city has spent decades specialising in cognitive labour: finance, law, consulting, policy, media, advertising, research, administration and professional services. These sectors trade not in physical output, but in judgment, drafting, interpretation, coordination and analysis.

That mix made London rich. It also makes London an early test case for what happens when machines become competent at precisely those tasks.

Generative AI does not arrive like an industrial robot, replacing a single job outright. It arrives as a force multiplier. One person, equipped with the right tools, can now do work that once required several. Productivity rises. Costs fall. Margins improve. None of that requires a mass layoff.

What it does require is fewer people at the entry and middle layers.

The mistake at the heart of the AI jobs debate

Public debate still treats AI as a blunt force that “destroys jobs”. That framing belongs to an earlier era of mechanisation. The evidence now points elsewhere.

AI reshapes labour by stripping out tasks within jobs rather than eliminating entire occupations. It targets routine cognitive work first: summarising documents, drafting standard text, checking compliance, searching archives, preparing first-pass analysis.

Those tasks historically anchored entry-level and mid-level professional roles. When they disappear, the job title often survives. The career pathway does not.

This is how class compression begins.

A familiar counterargument insists that cheaper professional work will simply expand demand — the so-called Jevons paradox. If AI lowers the cost of legal analysis or financial modelling, the reasoning goes, clients will consume more of it, preserving headcount.

That logic holds in energy and commodities. It breaks down in credentialed services. Litigation volume does not scale infinitely because clients still face budget ceilings and liability constraints. Cheaper first-pass analysis does not require more juniors; it allows fewer juniors to supervise vastly more machine output. Where demand expands, it accrues to partner leverage and margin — not to junior employment.

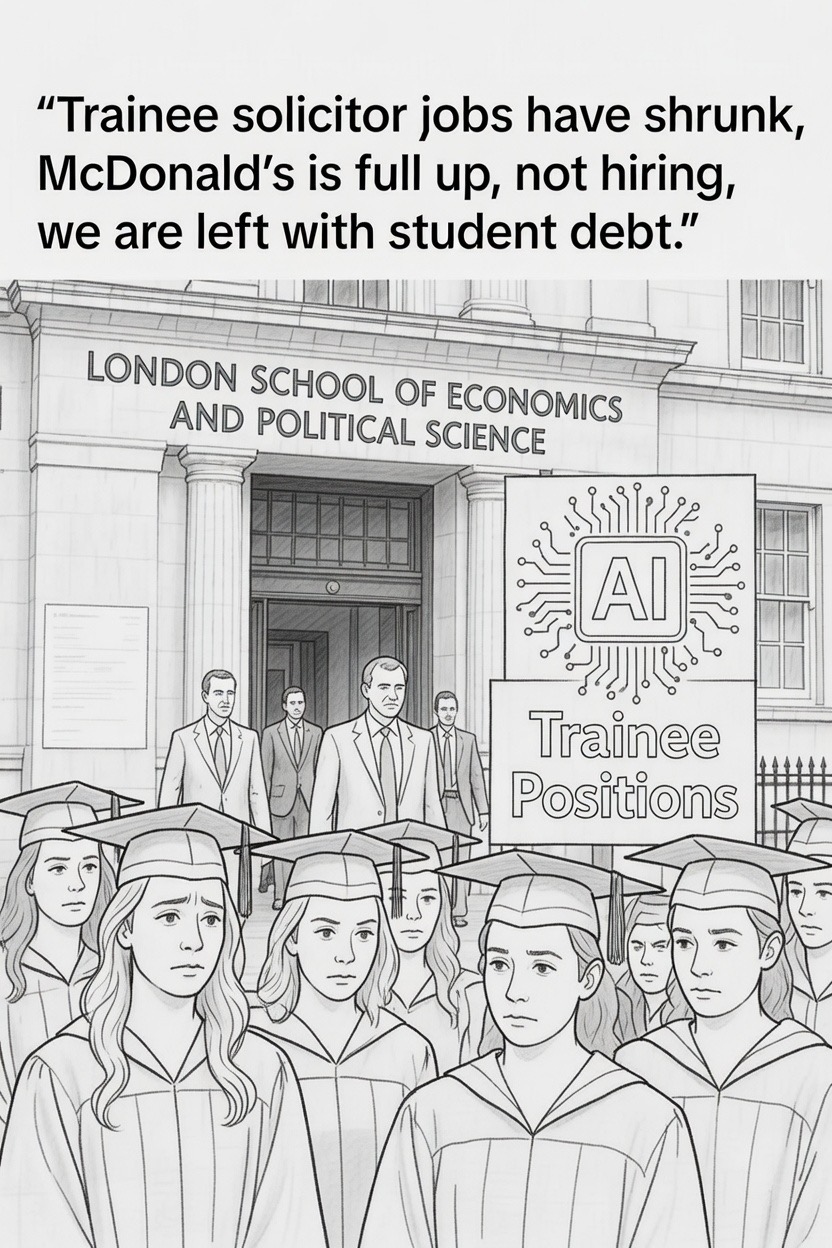

The collapse of the entry ladder

White-collar professions are built on ladders. Junior analysts, associates, trainees and assistants are not merely cheap labour. They are the training ground through which professions reproduce themselves.

AI compresses that structure.

In law firms, banks, consultancies and policy bodies, senior professionals increasingly draft, analyse and synthesise directly with AI assistance. The incentive is straightforward: fewer juniors, lower overheads, faster turnaround. The work still gets done.

What disappears are the rungs at the bottom.

This does not show up immediately in unemployment figures. It shows up in fewer openings, stalled careers, credential inflation and a quiet shift from open recruitment to informal gatekeeping. Over time, the middle of the labour market thins.

Regulation and liability slow this process, but they do not stop it. Professional services still require human sign off, and insurers still demand named responsibility. But liability preserves signatures, not headcount. One partner equipped with AI can replace several associates, trainees and paralegals while remaining fully compliant.

The training crisis no one is pricing in

There is a second-order effect rarely acknowledged in AI forecasts: the collapse of on-the-job training.

Junior roles are not only labour; they are the transmission mechanism of institutional knowledge. When they disappear, knowledge transfer breaks. Over time, future senior capacity erodes.

Institutions begin to cannibalise themselves drawing down accumulated expertise without replenishing it. The result is not lean efficiency, but brittle organisations with thinning benches and declining judgment.

In this sense, AI does not merely compress the middle. It destabilises the elite strata that depend on that middle for renewal.

Why service work survives while the middle shrinks

Here the story becomes counter-intuitive. The jobs least threatened by AI are often the lowest paid.

Catering, hospitality, cleaning, care work, transport, construction and maintenance depend on physical presence, real-world coordination and human interaction. AI can assist these roles with scheduling or logistics, but it does not replace their core functions.

London’s cafés will still need staff. Kitchens will still need chefs. Bars will still need people behind them.

At the same time, graduate white-collar roles narrow.

The result is not a city without work. It is a city where service work survives, elite work concentrates, and the professional middle quietly erodes.

Why this matters more than unemployment

Unemployment is visible. It triggers political response. Class compression is quieter. It unfolds slowly and plausibly. By the time it appears in statistics, the damage is already embedded.

Modern cities run on the discretionary spending of the middle: the people who rent housing, eat out regularly, use services, pay tax and sustain demand. When that group shrinks or stagnates, the economy weakens even if headline employment remains high.

A graduate working as a barista is “employed”. But they do not buy homes, invest or spend at scale. Multiply that across a generation and purchasing power erodes.

The slow demand shock

AI redistributes income upward. Productivity gains accrue to firms, platform owners and senior professionals. Below that tier, wages flatten or fall.

Consumption weakens. Margins thin. Service work becomes more precarious. Wages are suppressed further. Even sectors initially insulated from AI eventually feel the demand shock.

This is not a crisis moment. It is a slow squeeze.

Housing and the geography of compression

Nowhere does this dynamic bite harder than housing.

London’s economy assumes a large middle class capable of sustaining high rents. As middle incomes weaken, overcrowding rises, household formation slows and labour mobility declines. Asset owners remain protected. Rent extraction continues.

The effects are already visible: commercial vacancies driven not by collapse but by consolidation; thinning discretionary spend in central districts; weakened informal professional networks that once powered advancement.

This is not urban theory. It is what class compression looks like on the ground.

Ownership, not employment, is the fault line

AI concentrates value in ownership layers: models, data, compute and platforms.

London excels at consuming AI. It does not yet dominate its ownership. Productivity gains therefore leak outward while costs remain local.

The city risks becoming busy but brittle — full of activity, short on shared prosperity.

The feedback loop London prefers not to see

The danger lies in a reinforcing cycle:

- AI compresses junior and mid-level labour

- Middle incomes stagnate

- Urban demand weakens

- Firms cut further and centralise

- Professional ecosystems hollow out

- Political instability rises

None of these steps requires mass unemployment. Together, they produce long-term fragility.

The real choice London faces

Artificial intelligence will not empty London’s offices. It will narrow the city’s economic core.

The question is not whether London will keep working. It will. The question is who will be able to enter, progress and share in its prosperity.

If service work survives while elite work concentrates and the middle erodes, London will remain vibrant on the surface and fragile underneath.

That is the danger hidden behind the unemployment headlines — and the one this article set out to make visible.

AI in London will Cause Class Compression the Middle class will Erode

Artificial intelligence does not remove work evenly across all classes. It compresses it.

In London, the pattern is clear as the telegraph.com sees it.

- Service work survives because physical presence, human interaction and real-world coordination remain hard to automate.

- Elite professional work concentrates because AI amplifies senior judgment, ownership and leverage.

- The middle erodes as entry level and mid-career white-collar roles shrink, ladders break and progression slows.

This produces a second order effect that unemployment statistics miss: falling middle-class purchasing power as this class in London diminishes in number.

Demand weakens, urban ecosystems thin out, and institutions begin to cannibalise their own future capacity by cutting the very roles that once trained the next generation.

The danger is not that London stops working. It is that it keeps working while becoming narrower, poorer and more brittle.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

Artificial Intelligence

- Britain at the Crossroads: Teaching Resilience in the Age of AI — How artificial intelligence is reshaping work, learning and the skills that remain stubbornly human.

- From Lecture Hall to Algorithm: How AI Is Rewriting Authority — An examination of how AI is changing knowledge, expertise and institutional credibility.

- Beijing Writes the AI Rules While Washington Writes Press Releases — Why global power in AI is being shaped by state capacity rather than slogans.

Economy

- Britain’s Pressure Economy: Why 2026 Will Test Housing, Bills and Social Order — A deep dive into demand, housing stress and the economic squeeze on households.

- Why Artificial Intelligence Is Breaking GDP and What Comes After — How AI is distorting traditional economic measurement and what replaces it.

- New AI chatbot threatens white-collar remote workers — Reporting on how automation is reshaping professional employment.

Britain

- New Chinese Embassy in London and the Spy Tunnel Allegations — A case study in Britain’s changing political, legal and security landscape.

- HS2 as a Mirror: How Britain Lost the Ability to Build and Deliver — Infrastructure failure as a symptom of institutional decline.