Why There Is No Middle East Security Architecture and Why Iran Is Forced to Negotiate Deterrence Bilaterally Instead

There is no Middle East security architecture, only temporary firebreaks, because the region cannot aggregate interests long enough to name threats, bind commitments, or enforce outcomes.

In plain terms: the region cannot keep rival states aligned long enough to agree what the threat is, what the rules are, or how those rules would be enforced.

What exists instead is a rotating set of venues, brokers, and emergency conversations. When pressure rises, the region does not assemble. It fragments.

This absence explains the pattern that keeps repeating. Iran defaults to bilateral deterrence and ad hoc deconfliction rather than regional settlement. Crises produce meetings without mechanisms and statements without strategy. The language of a regional framework persists precisely because it never materialises.

The cost is predictable. Fragmentation increases miscalculation risk, locks crises into repeat cycles, and leaves escalation control to the narrowest channels at the worst moments.

The Delhi Declaration and the politics of omission

On 31 January 2026, India hosted the second India Arab Foreign Ministers Meeting and issued the Delhi Declaration. The format was broad. The language was careful. The ambition was deliberately limited.

What matters is not what the declaration says, but what it avoids. Functioning security forums identify proximate threats, define shared risks, and commit to enforceable mechanisms. Forums that cannot do this retreat into consensus language designed to offend no one and bind no one.

The Delhi Declaration exposes that limit. It presents the region as a diplomatic category, not as a security actor. The omission is structural, not accidental.

One concrete indicator is straightforward: the declaration discusses broad themes of peace and security and names the question of Palestine, but it does not set out any Gulf wide security framework and does not name Iran as a security problem to be managed collectively.

At this point the pattern is already visible. When confronted with an immediate security problem, the region can convene ministers, issue language, and signal concern. What it cannot do is agree on a shared definition of the threat, assign responsibility, or bind itself to enforcement. That failure is not episodic. It is systemic.

Why the Arab League cannot act when it matters

The Arab League problem: unanimity as paralysis

The Arab League is often described as the natural platform for regional security dialogue. In practice, its unanimity requirement converts disagreement into silence. Rival threat perceptions are not reconciled. They are suppressed.

This is not a failure of intent. It is a failure of design.

When core members pursue divergent security doctrines, competing alignments, and incompatible regional strategies, unanimity produces statements rather than decisions. In that environment, regional representation cannot function as a negotiating asset. It cannot bind actors who do not trust one another, and it cannot even agree on how to describe the threat landscape.

In plain terms: the mechanism is built to produce agreement language, not to force security choices.

Why the Gulf cannot anchor a regional framework

Gulf fragmentation blocks collective security design

Any viable regional security architecture would have to rest on the Gulf. That foundation does not exist.

The divergence between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates has translated into political rivalry, economic friction, and competing regional postures, particularly across Red Sea and Horn theatres. Analysts increasingly treat this as a sustained power struggle rather than a temporary disagreement.

This fragmentation matters because a divided Gulf cannot generate a unified security posture toward Iran.

Even where tactical de escalation aligns, strategic interests do not. The result is competitive hedging, not collective security design. The Gulf cannot anchor an architecture it does not share.

The operational consequence is simple: in crisis, Gulf states default to separate channels, not a single position.

Turkey is a venue, not a guarantor

Turkey: a venue, not a guarantor

Turkey illustrates the difference between facilitation and architecture. Ankara has positioned itself as a broker, urging step by step resolution of disputes and offering venues designed to reduce escalation and preserve diplomatic dignity.

That posture reflects Turkish incentives. War on its borders is costly. It does not create guarantor capacity.

The Istanbul format itself makes the point. These are crisis talks assembled through ad hoc invitations and framed explicitly as conflict avoidance. They are not negotiations emerging from a standing security framework. Turkey functions as a corridor and a convening space. It does not supply an enforceable system.

In plain terms: Turkey can host, shuttle, and soften edges. It cannot bind rivals to rules they do not share.

Pakistan imports volatility into every alignment

Pakistan: volatility imported into the regional equation

If the Gulf cannot aggregate and Turkey operates as a broker rather than a guarantor, Pakistan becomes a volatility amplifier.

In late January and early February 2026, coordinated attacks across Balochistan triggered a large scale security response, with authorities reporting the killing of 145 militants over roughly forty hours. The Pakistani government publicly blamed India. India rejected the accusation.

The attribution dispute is secondary. The effect is primary.

Episodes of this scale harden alignments, intensify blame dynamics, and pull actors further away from collective security design. Each crisis reinforces bilateral calculations: who backs whom, who is blamed, and which external patron matters.

This is how architecture dies in practice: the region turns inward, fractures into blame, and externalises security to patrons and proxies.

Why Iran defaults to bilateral deterrence

Iran’s default posture in an unaggregated region

In a region without a security table, Iran’s posture is adaptive rather than anomalous.

Iran negotiates where aggregation is possible: bilaterally or in small formats. It signals deterrence at chokepoints. It relies on the fact that others fear escalation costs more than they trust regional mechanisms to contain them.

This is why regional messaging increasingly emphasises avoidance rather than architecture. Calls for talks and long term solutions manage risk. They do not redesign the system.

The Iran US channel therefore forms as deconfliction first, not architecture building. Invited states may attend, but they do not constitute a mechanism that can guarantee outcomes.

Signals are not a security system

China and Russia: signalling without structure

China and Russia are often presented as alternative anchors. In practice, their role reinforces the same pattern.

Joint exercises, naval drills, and public signalling communicate deterrence and political alignment. They do not constitute a regional security architecture. Signals demonstrate presence. Architectures enforce outcomes. The region currently has the former, not the latter.

In plain terms: signalling can slow escalation. It cannot replace rules that bind states to commitments.

Fragmentation management is not security design

Fragmentation management is not security design

The central failure is not diplomatic inertia. It is architectural absence.

The Middle East does not lack meetings, mediators, or statements. It lacks a mechanism capable of aggregating interests, naming threats, and enforcing commitments across rival power centres.

Until that changes, security will continue to be managed through bilateral bargaining, ad hoc venues, and external signalling.

The region is not waiting for a security architecture. It is operating without one.

Either a binding framework emerges that rivals cannot evade, or the region remains trapped in perpetual crisis control, where the only question is how often the firebreak fails.

References

These readings align with the article thesis that the region lacks an enforceable security architecture and falls back on ad hoc venues, hedging alignments, and signalling rather than binding mechanisms.

Regional security architecture and why it keeps failing

Gulf: Promoting Collective Security through Regional Dialogue

International Crisis Group, 31 Jan 2023. Collective security is discussed as dialogue because binding enforcement remains structurally elusive.

The Middle East between Collective Security and Collective Breakdown

International Crisis Group, 27 Apr 2020. A direct treatment of the region oscillating between talks and breakdown rather than durable architecture.

Building a regional security architecture for the Middle East

IISS Manama Dialogue, 6 Dec 2024. A framework case for architecture and the obstacles that keep preventing it.

Fostering a New Security Architecture in the Middle East

Istituto Affari Internazionali, Oct 2020. A survey of repeated failed efforts and why hegemonic ambitions and rival alignments block durable mechanisms.

Turkey as facilitator, not guarantor

Turkey’s Mediation

UN Peacemaker paper, 2013. A primary articulation of Turkiye as a mediation actor built on facilitation rather than enforcement power.

The Importance of Turkey’s Mediation Role

Global Panorama, 5 Apr 2024. Distinguishes facilitation from guarantor roles in conflict diplomacy.

Mediating Conflicts and Turkiye’s Role as a Mediator for Peace

TRT World Research Centre, Sep 2024. Overview of Ankara’s mediation posture and its structural limits.

Gulf divergence and its strategic consequences

Power Struggle: What the Saudi UAE rivalry means for the Red Sea and Europe

European Council on Foreign Relations, 29 Jan 2026. Treats the rivalry as structural rather than tactical.

Risk, Order, and Power: The Saudi Emirati Divergence

War on the Rocks, 30 Jan 2026. Frames divergence as a driver of regional instability.

Note: This references box demonstrates that the article’s core diagnosis reflects a converging body of independent analysis across diplomatic, academic, and policy institutions.

You may also like to read on Telegraph.com

War With Iran Would Be Decided by Time, Not Power

A logistics-first argument: the war window is measured in days, not weeks, and constraint matters more than intent.

War with Iran: Does Anyone Still Have the Power to Stop a Process Already in Motion?

Why escalation hardens into expectation, and why force posture can become policy before anyone admits a decision has been taken.

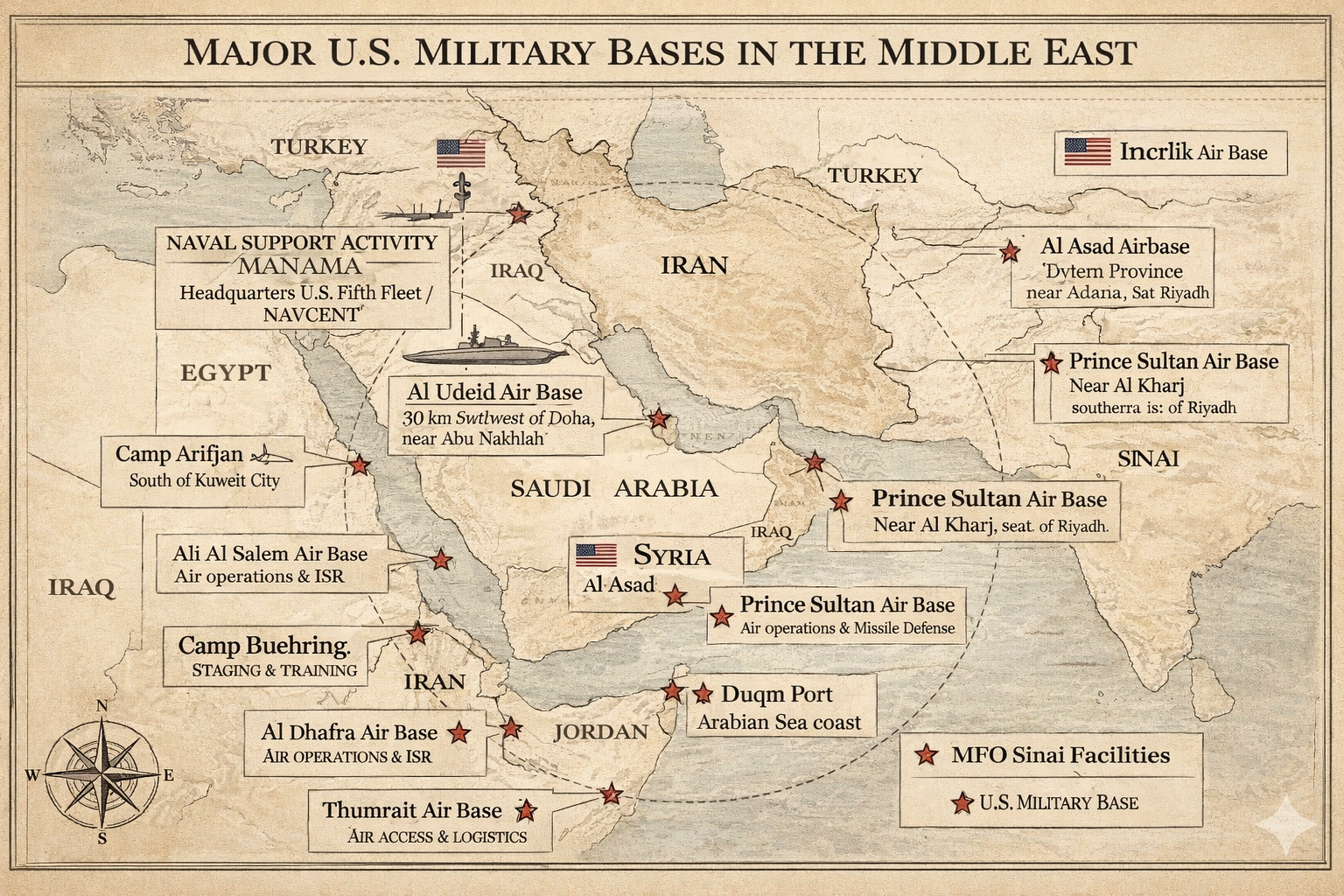

US Military Buildup Around Iran Signals Leverage, Not War

A measured reading of posture shifts and defensive preparations: warning signals without a declared trigger.

Iran Protests and Starlink: How Internet Shutdowns Crushed Momentum

How blackout strategy works in practice, why visibility collapses, and why satellite connectivity becomes part of the contest.

When the Sky Went Online: How Starlink Undermined Iran’s Internet Blackout

A narrative systems account of shutdown tactics, countermeasures, and why censorship has shifted from cables to spectrum.

Recasting the Region: Iran-Iraq Security Deal Narrows Israel’s Options

How the security map is being redrawn under pressure, and why state-to-state moves change the operational geometry.