New York Is Being Priced Out of Itself and Mamdani Is the Answer the City Chose

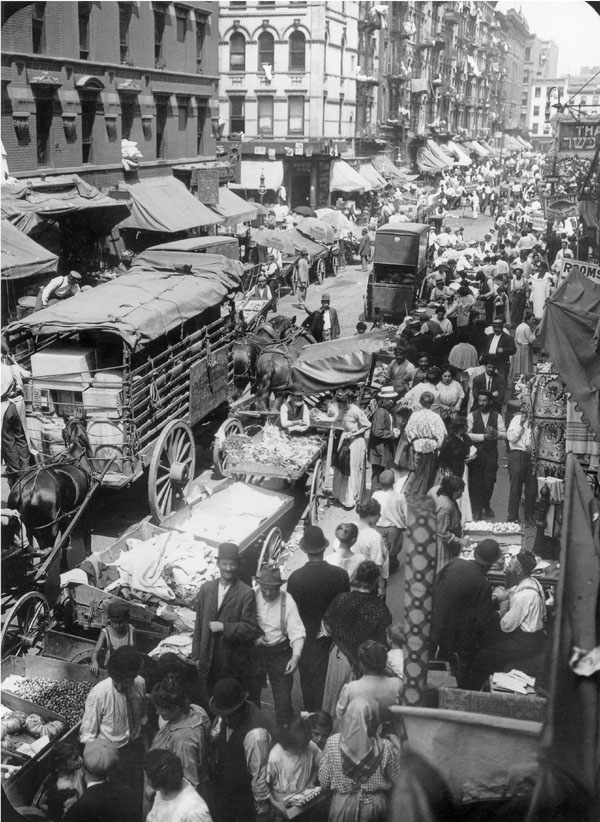

New York is not merely expensive. It is scarce. You can feel it in the hush after a viewing, the line on the sidewalk, the smile that is really a negotiation, the quiet calculation of what you will sacrifice to stay. A city that once absorbed people at speed now forces them to move carefully. The price is not only money. It is time, dignity, stability, and the right to live near your own life.

This is the backdrop to Zohran Mamdani’s rise. Not a trend. A mandate born from housing arithmetic.

New York still tells a comforting story about its housing crisis. It says the city is popular and nothing can be done. It says global capital arrived and the rest is weather. It says scarcity is natural, therefore cruelty is inevitable. It says the market is a force of nature and the only choice is to adapt, commute farther, live smaller, accept less.

This story is a sedative. It turns structural failure into personal advice. It also hides what is most important. The crisis is not a single villain or a single policy mistake. It is a system of incentives operating inside a scarcity condition. When vacancy collapses, power moves. When power moves, extraction becomes routine. The city does not need a conspiracy to be squeezed. It only needs a shortage and a set of institutions that have learned to profit from it.

The Numbers That Explain New York’s Housing Emergency

- Net rental vacancy rate (2023): 1.41 percent. A scarcity condition, not normal churn.

- Rent stabilised vacancy (2023): 0.98 percent. The regulated stock is effectively full.

- Rent distribution shift: a net loss of units renting $1,500 or less (2023 dollars) and a net increase of about 75,000 units renting $5,000 or more.

- Overcrowding: about 9.2 percent of rental housing is overcrowded.

Preliminary 2024 to 2025 indicators suggest no meaningful relief. Market surveys and city monitoring point to vacancy remaining near historic lows, with rent stabilised availability still effectively exhausted. The crisis is not cooling on its own. Time is not fixing this.

A 1.41 percent vacancy rate is not just a statistic. It is an atmosphere. It means the tenant who complains about mould knows the replacement will arrive tomorrow. It means a broker can add a fee, or a landlord can add a condition, and someone will accept it because the alternative is exclusion. It means choice becomes theatre. The side with time wins. The side with cash wins faster.

The rent distribution shift matters because it reveals the direction of travel. The crisis is not only that rents are high. It is that lower cost housing is disappearing while high rent housing grows. That is how a city changes character without ever voting to change it. It becomes a place that looks the same and feels different. The skyline remains. The working city thins out. The newcomers change. The people who built the neighbourhood are told, politely, to make way.

This is where the indictment must be careful. Scarcity is the enabling condition, but it is not the sole cause. Political choices, planning friction, financing incentives, uneven enforcement, and a professional ecosystem built around transactions all matter too. Scarcity does not invent every abuse, but scarcity makes every abuse easier to sustain. In a tight market, bad conduct faces fewer consequences because tenants have fewer exits.

How the squeeze works

In a normal market, a tenant can punish bad practice by leaving. In a scarcity market, leaving is expensive, uncertain, and sometimes impossible. That changes behaviour. It changes what owners can demand, what intermediaries can charge, and what conditions people will tolerate. A shortage turns housing into a test of endurance. It also turns the law into a slow instrument operating inside a fast pressure system.

That is why disrepair can persist even when the rulebook is clear. That is why informal displacement often does the work before court ever appears. That is why “rights” can exist on paper and fail in practice. Where enforcement depends on complaints, inspections, timelines, paperwork, and the ability to sustain pressure for months, the burden falls heaviest on those with the least time and the least slack. The system does not need to be illegal to be cruel. It only needs to be asymmetric.

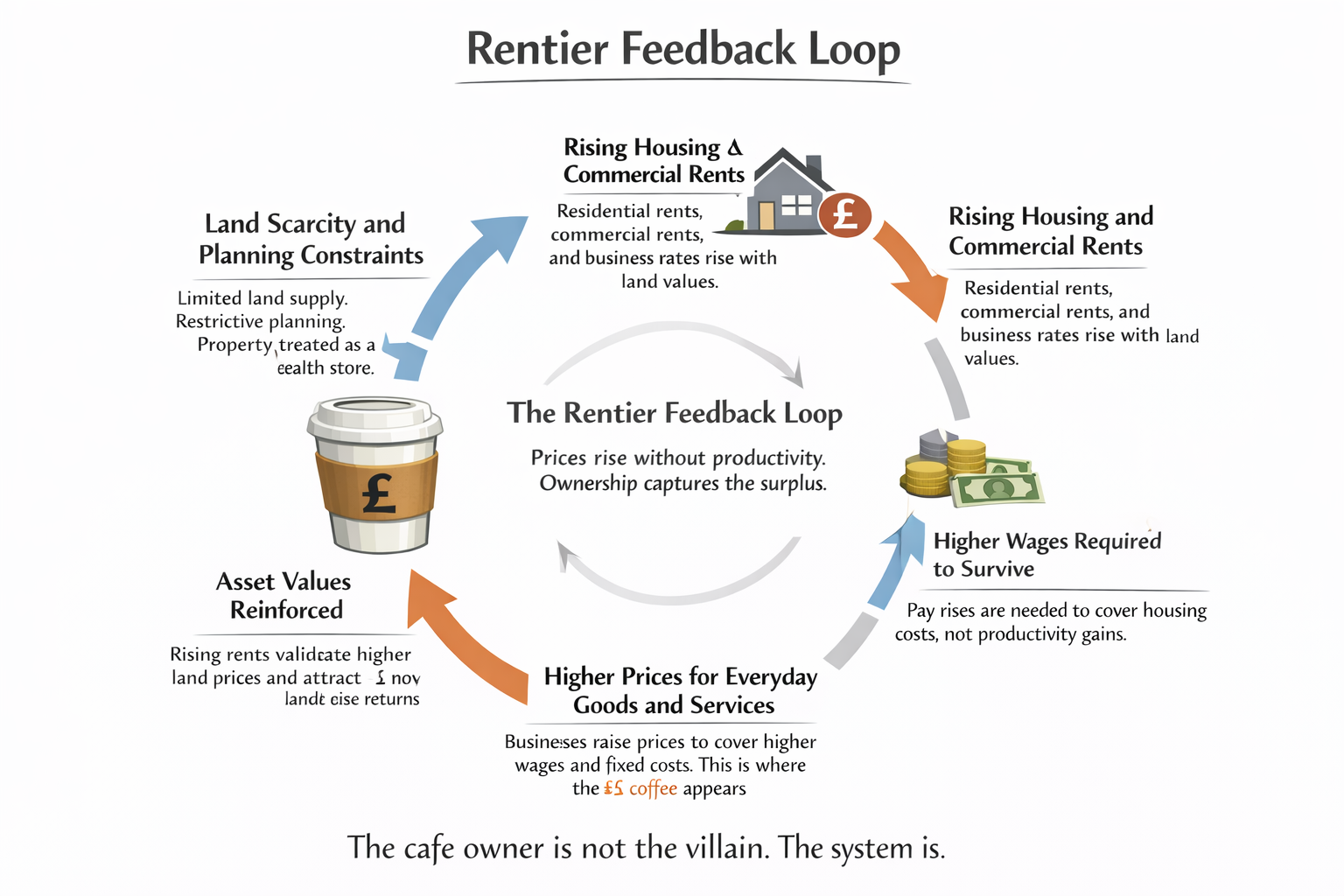

The cost stack

Rent is the visible price. What strangles New Yorkers is the stack beneath it.

In a scarcity city, housing costs do not arrive as a single monthly figure. They arrive as layers. Entry costs that drain savings before a key is handed over. Utility charges that swing sharply in a household budget that has no margin. Administrative fees that appear because the tenant is not in a position to negotiate. Moving costs that reset the stack again and again, sometimes after a dispute, sometimes after a notice, sometimes after a landlord decides the unit has more value without you in it.

Scarcity converts friction into revenue. Every step in the process becomes an opportunity to extract value because the alternative is exclusion. The market does not need to collude. It only needs to know that vacancy is thin and fear is thick.

This is why affordability arguments that focus on rent alone often understate what people experience. For lower income households, housing is no longer a stable monthly cost. It is a sequence of shocks. An upfront demand wipes out savings. A utility spike forces a trade off with food or childcare. A forced move resets the entire burden from zero. Over time the stack erodes resilience, shortens horizons, and turns ordinary life into a series of calculations made under stress.

“It wasn’t just the rent,” one Brooklyn tenant described. “It was the fee to apply, the fee to renew, the electric bill that doubled one winter, then the moving costs when the owner decided not to renew. Each thing on its own felt survivable. Together, they weren’t.” Housing advocates hear this pattern repeatedly: displacement not by a single blow, but by accumulated pressure.

This is also why enforcement that targets only the headline rent can miss the lived reality. A city can regulate rents and still allow the cost stack to do the work of displacement quietly, continuously, and legally.

Why the city elected Mamdani

Against this backdrop, Zohran Mamdani’s rise is not a media story. It is a structural one. A city reaches for a left wing mayor when the old equilibrium stops working. People voted for him because they want the housing system treated as a public emergency, not a private inconvenience. They want the city to stop behaving as if losing working families is normal. They want a government that is willing to make the pressure system less profitable.

Since the election, this mandate has already begun to take institutional form. In late 2025, transition briefings signalled early emphasis on aggressive housing code enforcement, consumer protection against fee abuse, and rapid audits of compliance in the most complaint heavy buildings. These moves are modest compared to the scale of the crisis, but they matter because they translate campaign rhetoric into administrative posture. They are early signals of whether power will be exercised or deferred.

This does not require turning the crisis into pantomime. Rogue landlords can exist as a category without naming firms. Speculation can be discussed without accusing a specific person of a crime. Corruption can be treated as a risk that has been reported and investigated in housing and shelter ecosystems, without turning this piece into an allegation machine. The point is not to shout. The point is to describe the incentives accurately, so the city understands what it is fighting.

Mamdani is the instrument the city chose because it believes something has to break. The mandate is action, but not fantasy. A mayor is not a monarch. City Hall cannot rewrite the state tax code. It cannot redesign national mortgage credit. It cannot rebuild the entire housing supply pipeline alone. If he pretends otherwise, he will be punished by reality and mocked by opponents.

Yet a mayor does have power. The power to enforce. The power to expose. The power to shorten the distance between law and life. The power to make predation costly and to make compliance normal. The power to force the city to speak in numbers rather than slogans. This is where the first months matter, not as theatre, but as credibility.

Singapore as the mirror, not the fantasy

To understand what New York can do, it helps to look at a city that refused to treat housing as a side issue. Singapore matters because it shows that affordability is not a mystery. It is the output of a system built to deliver housing at scale, and to suppress speculative heat when it threatens social stability. Singapore’s housing model is not romantic. It is engineered.

Start with the basic architecture. Public housing in Singapore is not a narrow safety net. It is the main channel for ordinary life. Most resident households live in HDB dwellings. That means the state has a production arm with real volume. It means housing delivery is managed as infrastructure, with planning, scheduling, and continuity. It also means the government can influence prices and access through policy design rather than pleading with the private market after the fact.

Then consider demand discipline. Singapore does not ask the market to behave. It disciplines it. When prices rise too fast, the government makes speculative behaviour more expensive and borrowing more difficult. Buyers of second or third homes face heavy additional stamp duties. Short term resales are penalised. Loan rules are tightened so households cannot borrow beyond defined income limits or leverage themselves into fragility. When necessary, authorities openly warn citizens about buying at inflated prices and adjust the rules again.

These tools are not symbolic. They are designed to change behaviour quickly. Investors pull back. Households think twice. Momentum slows. Demand is cooled deliberately, not hoped away. Singapore still faces price pressures, which is precisely the point. Even a housing state must keep tightening the valves when the system overheats. But it has valves. New York mostly has speeches.

The comparison is not a demand to copy Singapore. It is a spotlight on missing levers. Singapore is a city state with a centralised capacity to treat housing as a national project. New York is a city inside a state, operating inside a constitutional culture that treats property rights as near sacred and governance as fragmented by design. The lesson is not imitation. The lesson is seriousness. Housing delivery must be treated as a pipeline. Speculative demand must be treated as a risk to social order, not as a harmless expression of preference.

What New York Can Borrow from Singapore, and What It Cannot

Borrowable now, within City Hall:

- Publish a housing pipeline: a clear public list of sites, approvals, starts, and completions, with quarterly delivery targets that can be audited.

- Industrialise delivery where possible: standard designs, pre approved typologies, faster procurement, and build methods that cut time and cost.

- Use public land as leverage: long leasehold deals with strict affordability covenants, completion deadlines, and reversion if promises are not met.

- Attack the cost stack: pricing transparency, fee discipline, and consumer protection enforcement that makes routine extraction harder.

Borrowable only with Albany and federal cooperation:

- Demand cooling: investor penalties, anti flip rules, and tax tools that can change behaviour at scale.

- Credit discipline: leverage limits and debt service rules that curb fragile borrowing and speculative heat.

- A public builder with real volume: durable funding and state level settlement to expand supply beyond the cycle of headlines.

Not realistically transferable: Singapore level land dominance and full administrative allocation as the main housing channel.

The counterargument, and why it fails alone

The most common counterargument is simple: build more market rate housing and the problem will solve itself. New supply matters. But in a city with a collapsed vacancy rate and a rent distribution drifting upward, the just build argument often becomes a way to postpone hard choices about who the city is for. New York can build and still lose lower cost housing if the pipeline is not aligned with affordability outcomes and if speculative demand keeps pulling the price ladder higher.

New York’s own recent building cycle illustrates the problem. Large volumes of luxury and upper market units have come online over the past decade, yet lower cost rents have not meaningfully fallen. In a city with near collapsed vacancy, new high end supply is absorbed at the top, stabilising returns rather than cascading downward. Filtration is slow, partial, and easily overwhelmed by demand pressure. In practice, it has not rescued affordability for the households now under the greatest strain.

This is where Singapore is again the mirror. It is not anti supply. It is supply at scale plus demand discipline plus a public role that is large enough to shape the market rather than plead with it. New York does not need to nationalise housing to learn that lesson. It needs to stop pretending that the private market alone will choose social stability over maximum rent.

What delivery must look like

Now we return to Mamdani and the point of his election. The hope is real, but it is conditional. He will be judged on results, not intention. He does not need miracles. He needs measurable movement.

There are two tracks. The first is immediate, because it is within mayoral reach. It is enforcement, transparency, and the cost stack. The second is structural, because it requires Albany, financing, planning reform, and time. The danger is confusing the first with the second. Enforcement can win the first months. Only a pipeline can win the decade.

A Practical Delivery Agenda: Seven Tests of a Serious Housing Mayor

What follows is not a wish list but a public scorecard, a framework journalists, tenants, and civic groups can use to track whether the administration converts mandate into measurable change.

- Test 1, the first 100 days: publish a citywide enforcement surge plan for the worst building conditions, with timelines and outcome reporting.

- Test 2: launch a cost stack crackdown focused on fee transparency and repeat abusive practices, with penalties that change incentives.

- Test 3: publish the housing pipeline quarterly, site by site, with start and completion targets, and explain delays in plain terms.

- Test 4: use public land with hard covenants, hard deadlines, and reversion clauses if delivery fails.

- Test 5: negotiate Albany support for demand cooling tools that curb speculative heat and reward long term occupancy.

- Test 6: push a plan for large scale delivery that does not rely on one off deals, but on repeatable production.

- Test 7, the trust test: keep the coalition intact by proving that the city will not trade working life for luxury optics.

New York is a community. It is a city beloved. It should not become a city that trains its young to leave and trains its poor to disappear. The housing crisis is not only a private hardship. It is a public fracture. A city that prices out nurses, teachers, drivers, cooks, cleaners, and young families does not become more sophisticated. It becomes brittle. It becomes a museum with an attitude.

That is why Mamdani was elected. Not because New York wanted a new mood, but because it wanted a new direction. The hope remains conditional because the pressure system is real and the interests embedded in it are experienced. If he delivers visible enforcement, a credible pipeline, and a serious push for demand discipline, the city has a way out. If he does not, New York will keep sliding toward a gated economy that calls itself a metropolis.

What Accountability and Solutions Would Look Like Next

1. Follow the money, properly.

A serious housing reckoning would require tracing which major residential developments were stalled or abandoned over the past two years, which organised interests opposed them, and how campaign finance, lobbying, and legal intervention interacted. That work has not yet been done in public. Until it is, the system’s most consequential decisions remain deliberately opaque.

2. Measure the lived cost of exclusion.

One way to make housing inequality visible would be a simple, repeatable metric: the gap in average commute times between the city’s service workforce and its professional elite. As housing pushes essential workers outward, time becomes a hidden tax. Tracking this ratio would show whether affordability policies are actually bringing the city back together.

3. Add a market discipline countermodel.

Singapore is not the only alternative to New York’s paralysis. Tokyo offers a conservative solution with progressive outcomes: extensive by-right development, predictable zoning, and rapid approval that allow supply to respond without political theatre. A full comparison would show that housing affordability does not require ideology — it requires rules that work.

Together, these lenses move the debate beyond abstraction. They replace slogans with accountability, metrics, and workable contrasts.

References and Data Sources

- NYC Housing and Vacancy Survey (2023, subsequent monitoring) — New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Baseline vacancy rate (1.41 percent), rent stabilised vacancy (0.98 percent), rent distribution shift, overcrowding indicators.

- NYC Rent Guidelines Board — Housing Supply Report and Income and Affordability Study (recent editions). Rent burden metrics, supply trends, overcrowding estimates.

- NYC Department of City Planning — Housing Production Snapshot and pipeline reporting. Permits, starts, completions, and unit mix.

- NYC Office of Civil Justice — Housing Court representation data and reported outcomes, documenting the link between legal access and housing stability.

- New York City Council and Office of Management and Budget — Department of Homeless Services budget allocations and shelter census reporting.

- SingStat (Singapore Department of Statistics) — Resident households by dwelling type, confirming majority residence in HDB housing.

- Singapore Ministry of National Development, MAS, IRAS — Official statements and guidance on cooling measures, including additional buyer stamp duty, resale restrictions, and loan to value tightening.

- Mamdani transition communications (late 2025) — Public remarks and transition briefings indicating early enforcement posture and consumer protection priorities.

- Academic and policy literature — Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy and related research on supply constraints and limited rent filtration in low vacancy cities.

Figures reflect the most recent publicly available baselines and monitoring as of late 2025. Where 2024 to 2025 updates are provisional, they indicate persistence rather than reversal of the underlying trends.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

- The Rent Crisis Was Manufactured To Serve Profit Not Shelter

A Britain focused diagnosis of how deregulation, Right to Buy depletion, land banking, and financialisation pushed rents into the wage base. - Sex for Rent Scandal Landlords Exploit Britain’s Broken Housing Market

A grim illustration of how scarcity and power imbalance turn housing into coercion, and why enforcement often arrives too late. - Fifth Floor Christmas Day

A social realism report anchored in official UK homelessness and temporary accommodation figures, with the human cost left visible. - The Sick Man of Europe Again Britain Enters the Great Crisis

On stagnation, public service strain, and the national conditions that convert housing stress into wider social fracture. - Rachel Reeves UK Budget 2025 A Critical View

An inequality lens on Britain’s fiscal choices, who pays, who escapes, and how distributional decisions shape deprivation. - Why Britain Feels So Bitterly Divided and Why the Explanations Are Wrong

A numbers first account of how housing, wages, and uneven opportunity feed polarisation beneath the culture war noise. - Britain’s Borrowing Costs Surge to 27 Year High Reviving Old Fears of Fiscal Strain

Why fiscal pressure matters for housing, local government capacity, and the ability to fund any serious social repair. - Britain’s Trump Moment Farage Reform and the ECHR Exit

A working class revolt viewed through institutions and legitimacy, with economic strain as the underlying accelerant. - Flags Protests and a Fractured Identity Inside England’s Weekend of Patriotism and Anxiety

A ground level look at anxiety politics where housing insecurity and affordability pressure sit behind the mood. - The Betrayal Dividend How Labour Lost the Working Class and Lit the Fuse for a Two Front Revolt

On long run neglect, distrust, and the material conditions that turn deprivation into a permanent political engine.