Hanukkah and the Covenant of Light

Hanukkah is often reduced to a pleasant domestic scene: candles, songs, simple foods, and gifts. But the mitzvah of ner Hanukkah was never meant to be seasonal decoration. It is a public act of Jewish memory and Jewish loyalty. It is Judaism practiced outwardly, deliberately, and with restraint.

The Talmud asks a striking question: Mai Chanukah? What is Hanukkah? It is not asking for a history lesson. It is asking something far more demanding: what is the essence of this day that must be preserved and practiced across generations.

The answer it gives is not a military narrative. It is the miracle of the cruse of pure oil, the eight days, and the obligation to light and to publicise the miracle: pirsumei nisa. That choice is itself instructive. Jewish life is not built only on what happened, but on what Jewish law and Jewish wisdom decide must be carried forward as the living heart of the event.

There is no need to deny history. The Hasmonean struggle was real. The rededication of the Temple was real. Jewish sources preserve that victory and that restoration. But the rabbis did not establish Hanukkah as a holiday of kingship. They established it as a holiday of light.

Not because they were naive about power, but because they understood the Jewish condition across time. Sometimes Jews live with sovereignty. Often they do not. Yet the covenant cannot be allowed to rise and fall with politics. The mitzvah must remain possible in every place, in every home, in every generation.

So the story is sanctified through a ritual that does not require an army or a palace. It requires a wick, oil, and a Jewish house that refuses to go dark.

The law itself makes the philosophy unavoidable. The central demand of Hanukkah is pirsumei nisa, publicising the miracle. The light belongs in the public facing place: at the threshold or the window, facing outward. It is a rare religious act that insists memory must be visible. Not aggressive. Not theatrical. Simply present.

The medieval sage Maimonides describes the Hanukkah light as a deeply beloved obligation and insists that even those of limited means must find a way to light it. This is not a luxury ritual. It is a declaration of belonging and gratitude.

In plain terms, one does not light because one is comfortable. One lights because one is responsible.

The candles teach a permanent Jewish tension: how to live among other cultures with dignity, without dissolving into them. The pressures faced by ancient Jews were not only political. They were cultural and spiritual. They offered beauty, status, and acceptance at the price of distinctiveness.

Hanukkah answers with a disciplined refusal. It does not reject the world. Judaism has never taught withdrawal from humanity. But it rejects assimilation as a condition of peace. It rejects the idea that love of others requires the erasure of self.

That is why the candles are placed where they can be seen. The act insists that Judaism is not only a private feeling. It is a public loyalty.

Much is said about light in the darkness at this time of year. Judaism does not rest on slogans. It turns words into practice. A small flame, lit again and again, trains the soul not to panic. Darkness is not negotiated with. It is pushed back patiently, one night at a time, until there are eight lights and the room itself is changed.

The miracle of Hanukkah is not only that the oil burned. It is that a people learned how to keep burning when history tried repeatedly to extinguish them.

Hanukkah is not primarily about nostalgia. It is about continuity. The world will always offer Jews the same bargain: be less visible, be less particular, be less demanding, and you will be more accepted. Hanukkah teaches that this bargain is never free. It always costs something essential.

The Hanukkah candle therefore becomes a quiet, stubborn answer. We will not vanish. We will not apologise for being a people of Torah. We will not reduce holiness to whatever is fashionable. We will light, and we will remember, and we will do so in the shared public space of the world.

And the light itself makes a further claim. It is not meant to burn others. It is meant to warm. It is not a weapon. It is a witness. The peace Judaism seeks is not achieved through invisibility, but through faithfulness without hatred, firmness without cruelty, and love grounded in responsibility.

That is why this mitzvah sits in the window.

Not for decoration.

For testimony.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

- Why Jewish Humour Is Not Self-Deprecation

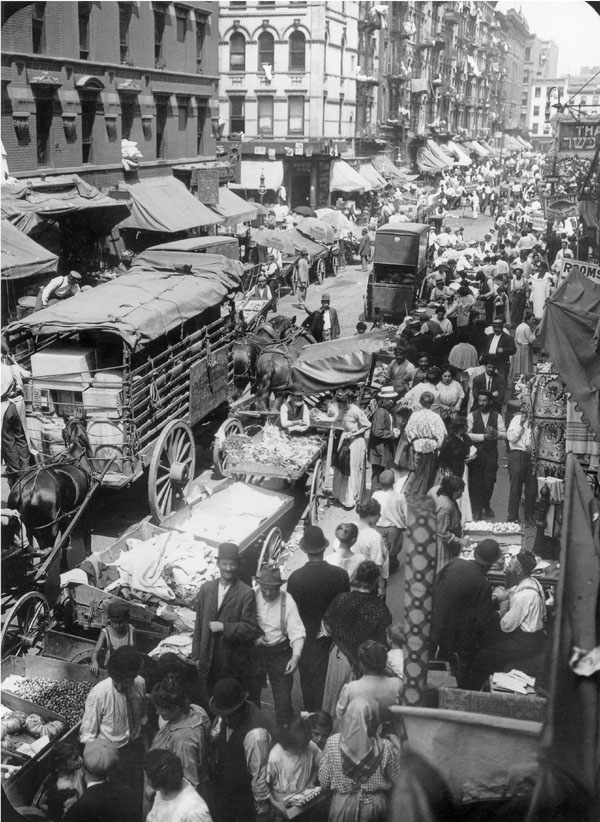

- The Language the City Forgot

- Yom Kippur Sermon: Peace Amid Ashes

- Ashkenazi Ethics and the Burden of Conscience

- Holocaust Survivor at the Center of Britain’s Crackdown on Pro-Palestinian Protests

- Yiddish New York: A Living Heritage of Torah, Safety, and Continuity

- Tikkun Olam: The Jewish Call to Repair the World

References

- Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 21b (Mai Chanukah; pirsumei nisa)

- Maimonides (Rambam), Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Megillah v’Chanukah (laws of Chanukah)