Code Red at the Frontier: GPT 5.2, Gemini 3 and the Arms Race That Buries Safety

Sam Altman’s reported “code red” after Google’s Gemini 3 outperformed ChatGPT is not a stray managerial outburst. It is a public marker that the frontier model race has entered a new phase. OpenAI, Google, xAI and soon Microsoft’s own models are now locked into a feedback loop of benchmarks, capital and fear of being overtaken, with safety treated as a luxury add on rather than a design constraint.

From playful rivalry to existential competition

For a year, the story at the frontier was still comfortable for Silicon Valley. OpenAI had first mover advantage with GPT 4 and the ChatGPT brand. Google stumbled with early Gemini branding and then started to recover. Anthropic positioned itself as the careful cousin. xAI talked about truth seeking. The race looked busy, but not yet existential.

Gemini 3 changed that mood. Google’s own material describes it as its most capable model so far, with a strong focus on reasoning and tool use that is designed to support personal agents and parallel workflows rather than just pretty chat outputs. Demis Hassabis presented Gemini 3 as a clear step on the path toward general intelligence rather than a routine product refresh. At the same time, the Gemini 3 Deep Think option, reserved for premium subscribers, has posted leading scores on hard reasoning benchmarks such as Humanity’s Last Exam and ARC style tests.

At that point the technology story and the market story merged. A new model does not just change the leaderboard. It moves investor expectations, enterprise purchasing and talent flows. OpenAI had been edging into a familiar position: famous brand, heavy losses, expensive plans to build its own power scale, and a user experience that no longer felt obviously ahead of the pack. A serious Gemini lead on the hardest benchmarks was enough to trigger Altman’s “code red” memo and an explicit decision to pull focus back to the core model rather than side projects.

Key benchmarks in the frontier arms race

- Humanity’s Last Exam – about 2,500 expert level questions across mathematics, science and humanities, designed to be extremely hard for current models.

- ARC style benchmarks – tests that focus on general reasoning and pattern discovery rather than exam cramming.

- Tool enabled scores – benchmarks that allow the model to call tools such as code interpreters or search as part of a longer thought process.

These tests have become the new scoreboard for executives and investors who want a simple line: who is ahead on “real intelligence” rather than party tricks.

GPT 5.2: a rumour, a signal, and a deadline

Into this environment drop the leaks and rumours about GPT 5.2. Various reports and trading markets have converged on the idea that OpenAI will ship a substantial upgrade to its main model in December, with the internal target pulled forward by code red pressure and explicit intent to match or beat Gemini 3 on Humanity’s Last Exam and related reasoning benchmarks.

The exact timing and capability claims remain unconfirmed, but the pattern matters more than the date. The market now assumes a cadence in which:

- Google releases Gemini 3 and then Gemini 3 Deep Think, with strong reasoning scores.

- OpenAI responds with GPT 5.2 and frames it as a direct answer to Gemini’s lead.

- xAI hints that a new Grok release is coming that can self finance through trading and search products.

- Microsoft prepares to place its own name on an internal line of models rather than depending entirely on its OpenAI partnership.

That looks very much like a weekly or monthly leapfrog cycle. Each new model becomes less a research event and more a market promise: we will not be left behind, and we will keep spending until that is true. In that environment, rumours themselves become tools. Hinting that you have a model in hand that will beat your rival’s benchmark score can move perception and help you raise capital even before the model ships.

What “code red” really does inside a lab

It is tempting to treat “code red” as a media phrase. It is not. It is a specific management device, and we have seen it before. Google used a similar internal framing when ChatGPT first threatened its search franchise. Brin and Page were reported to have stepped back into founder mode, pulled senior teams into war rooms, and told them that this was now the priority.

Altman is now doing the same thing from the other side of the table. A code red memo does three jobs at once:

What “code red” does inside a company

- Refocuses staff – side projects and experiments are quietly deprioritised. The core model and its user experience move to the centre of the roadmap.

- Signals investors – it tells current and future backers that leadership understands the threat and is willing to act, even if that means cutting pet initiatives.

- Justifies capital demands – it provides a political story for asking for power station levels of funding for data centres, memory and chips.

In other words, “code red” is less about panic and more about permission: permission to shift resources fast and to ask for more money than would otherwise be politically comfortable.

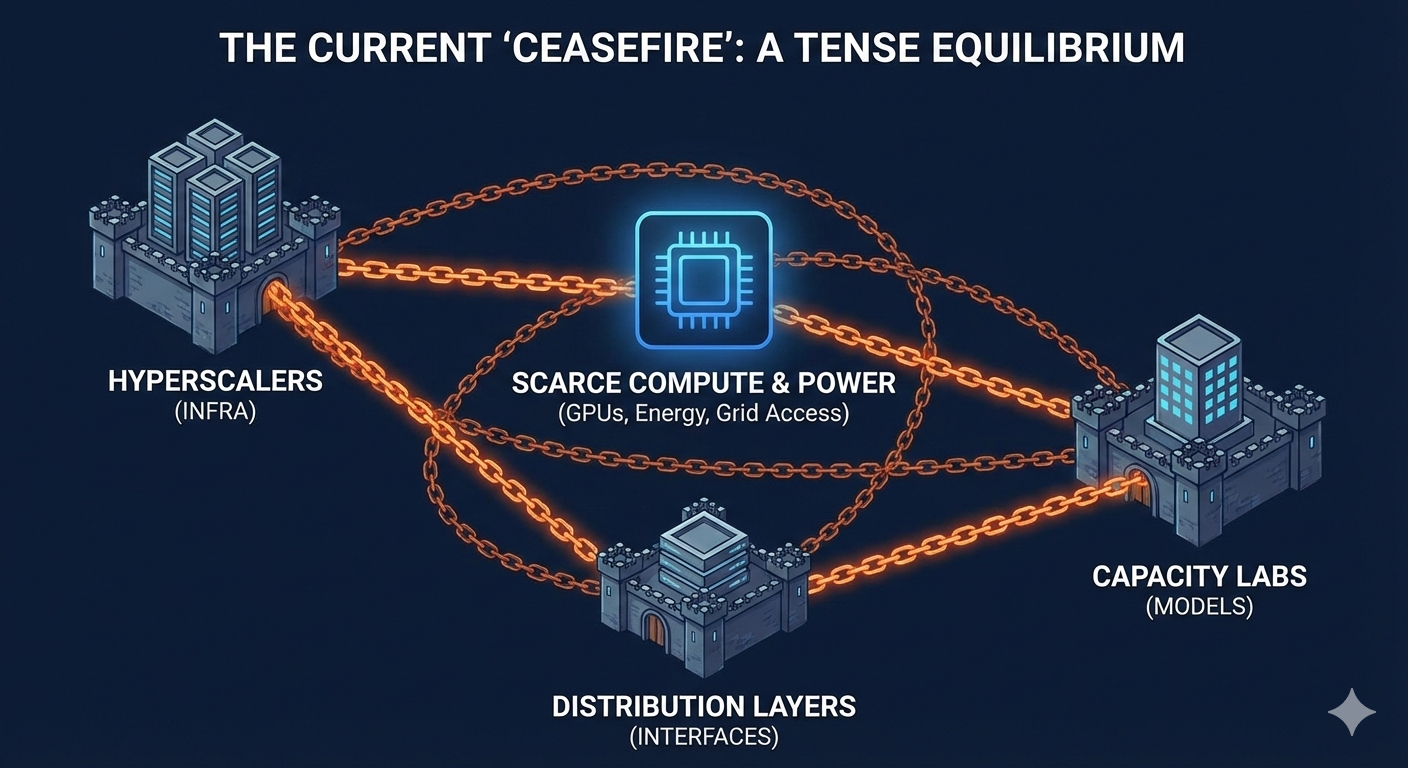

From a distance, this looks like rational competition. A serious rival appears, you reorient your resources and you tell your owners why. The problem is that in the frontier model context, the numbers are no longer those of a normal software company. OpenAI’s own ambitions for dedicated data centres and chip supply run to tens or hundreds of billions of dollars over a few years. Google, Microsoft and Amazon are making similar bets on power, land, cooling and high bandwidth memory. Once you have committed to that level of capital, you cannot afford to be second best on the scoreboard for long.

The new bargain with investors

In this environment, the relationship between frontier labs and their investors is becoming brutally simple. The lab promises:

- We will stay at or near the top of the hardest reasoning benchmarks.

- We will translate that lead into products that lock in users and enterprises.

- We will expand agent fleets and tool use so that each point of benchmark gain turns into visible revenue.

In return, investors accept multi year losses and agree to finance energy hungry infrastructure that looks more like a utility than a tech stock. The logic is familiar from other network effect races: the winner will be able to extract rent for a very long time, so it is rational to tolerate absurd burn rates now. The twist is that this time, the infrastructure is not just servers and bandwidth. It is transformers, high bandwidth memory, power lines, copper, cooling and even the first sketches of orbital data centres.

Against that backdrop, a benchmark like Humanity’s Last Exam becomes a kind of proxy share price for insiders. A jump from the mid thirties to high sixties in accuracy on a graduate level reasoning test can be used to justify another fund raise or another round of bond issuance. The risk is obvious: if benchmark scores are allowed to stand in for business fundamentals, they will be treated as a target rather than a measure.

Safety in a rat race

In public, all of the frontier players talk about safety, alignment and responsible deployment. They publish model cards and host summits. They sign letters in Brussels, London and San Francisco. None of that changes the basic industrial logic.

When you declare code red in a laboratory that is already spending billions, the easiest costs to cut are the ones that do not show up on the leaderboard. Safety and governance work has three features that make it politically fragile inside a rat race:

Signals that safety is being sidelined

- Safety work is hard to measure – a red team that prevents a failure leaves no number on a chart. A new benchmark score is visible at a glance.

- Safety slows release – serious evaluations and deployment gates add weeks or months in a world that is trying to ship new frontier models every quarter.

- Safety is culturally separate – governance and policy teams often sit outside the core engineering power structure, with less ability to veto rushed plans.

In a genuine race, all of those features become liabilities. Anything that cannot be shown to improve the next benchmark score risks being treated as a “nice to have”.

There is also a more subtle effect. When executives are fixated on beating a specific competitor on a specific benchmark, they are incentivised to tune for that test. Humanity’s Last Exam is supposed to be difficult to game. It mixes subjects, uses unseen questions and demands multi step reasoning. Yet the moment investors and executives frame it as the exam that proves who is ahead, they create pressure to train and scaffold models around that one measure. This is Goodhart’s law applied to intelligence: once a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure.

What should boards and regulators do?

The easy response is to complain about the race. The harder and more realistic response is to assume that the race will continue and to shape the incentives inside it. Boards of companies that consume frontier models, and regulators in states that host the infrastructure, should be asking three blunt questions:

- What are we actually optimising for: benchmark scores, revenue, risk control, or some mix of all three?

- Who inside the pipeline can veto a rushed release when safety work uncovers a serious concern?

- What external tests are we willing to respect even when they show that our favourite model underperforms a rival?

There is no credible pathway in which the United States or Europe simply ask Google, Microsoft, OpenAI and xAI to slow down and they politely agree. China is building its own parallel stack. Smaller players are chasing market share with open weight models. Sovereign states want their own capacity. The race exists because the prize is real: whoever builds the most capable general intelligence and embeds it deepest into the economy will set standards and capture rents for a generation.

The practical question is therefore narrower and sharper. Can we design governance arrangements in which code red cannot be used as an excuse to bypass safety, and in which benchmark numbers are treated as one signal among many rather than the only story executives and investors care about? If we cannot, the next few years of weekly leapfrogging will leave us with very capable systems, very deep sunk costs, and very little clarity about what exactly we have created or who really controls it.

You may also like to read on Telegraph.com

- Who Gets to Train the AI That Will Rule Us – how control over training pipelines becomes political power.

- China’s Offshore AI Training After the Nvidia Beijing Ban – how China responds when access to top chips is cut.

- The Quiet Land Grab for AI Training Data – and Who Gets Paid – the extraction economy behind frontier models.

- The End of the Page: How AI Is Replacing the Web We Knew – why the old layout web is already disappearing.

- The End of Search: How AI Will Destroy the Old Gatekeepers of Knowledge – on the collapse of legacy discovery systems.

- London Leads Europe in AI – But Not in Power – why the real bottleneck is energy, not clever code.

- The Missing Ingredient in Machine Intelligence – what current benchmarks still fail to capture.

- AI, Manipulation, and the Strange Loop – how systems learn to push our emotional buttons.

- Robotaxis and the AI Infrastructure Race – when cars become rolling inference nodes.

- AI Will Not Arrive as an App – why the real shift is system level and infrastructural.

References

Editor’s note: for fact checking and legal review. Not for inclusion in the public article body.

| Source | Relevance |

|---|---|

| Fortune, “Sam Altman declares ‘Code Red’ as Google’s Gemini 3…” (2 Dec 2025) | Reports the code red memo at OpenAI and links it directly to Gemini 3’s performance. |

| Telegraph.com and other coverage of OpenAI’s capex plans (late 2025) | Details the scale of data centre and chip investment OpenAI is seeking and projected losses. |

| Google DeepMind, “Introducing Gemini 3” (Nov 2025) and Gemini 3 Deep Think launch posts | Positions Gemini 3 as Google’s most capable model and emphasises reasoning and tool use. |

| Humanity’s Last Exam official site (Center for AI Safety / Scale AI) | Defines benchmark structure, subject mix and difficulty; establishes it as a frontier reasoning test. |

| Scale AI Humanity’s Last Exam leaderboard (late 2025) | Shows relative performance of Gemini 3, OpenAI and other labs on the benchmark. |

| Reporting on GPT 5.2 leak and Polymarket contracts (Nov–Dec 2025) | Evidence that markets and insiders expect GPT 5.2 to be brought forward as a direct response to Gemini 3. |

| BusinessChief and other outlets on OpenAI “code red” | Summarises internal memo language and frames it as an effort to push faster model improvement. |

| Turing Institute blog, “LLMs have been set their toughest test yet” (2025) | Explains why Humanity’s Last Exam was created and why benchmark games are a risk. |