China’s AI Governance Model vs America’s Frontier Race: Why the Real Battle Is Over Who Can Control Intelligence at Scale

China’s AI Order: Why Beijing May Win the Governance War

As Washington tightens chip export controls and Beijing moves to regulate emotional AI systems that simulate human personality, the contest is no longer about who builds the smartest model. It is about who can govern intelligence at scale without losing social stability.

The Governance Turn

Two developments illustrate the shift.

In Washington, lawmakers continue pressing to restrict China’s access to advanced semiconductor tools. AI competition is framed as hardware denial and frontier acceleration.

In Beijing, regulators have circulated draft measures targeting human like interactive AI services, systems that simulate personality traits, emotional bonding, and conversational intimacy. These are not treated as novelty products. They are treated as governance objects.

These moves reveal a deeper divergence. The AI contest is no longer just about model capability. It is about system design: how intelligence integrates into national infrastructure, labour markets, information environments, and geopolitical strategy.

One plausible scenario is this: the winner of the AI era will not be the actor with the best chatbot, but the actor with the most coherent governance architecture.

Key implication

- The decisive contest may shift from model quality to state and institutional capacity: who can absorb labour shock, govern influence systems, and provision compute without political fracture.

- In that frame, governance becomes a competitive advantage, not a constraint, and legitimacy becomes a strategic resource.

Two Mobilisation Stacks

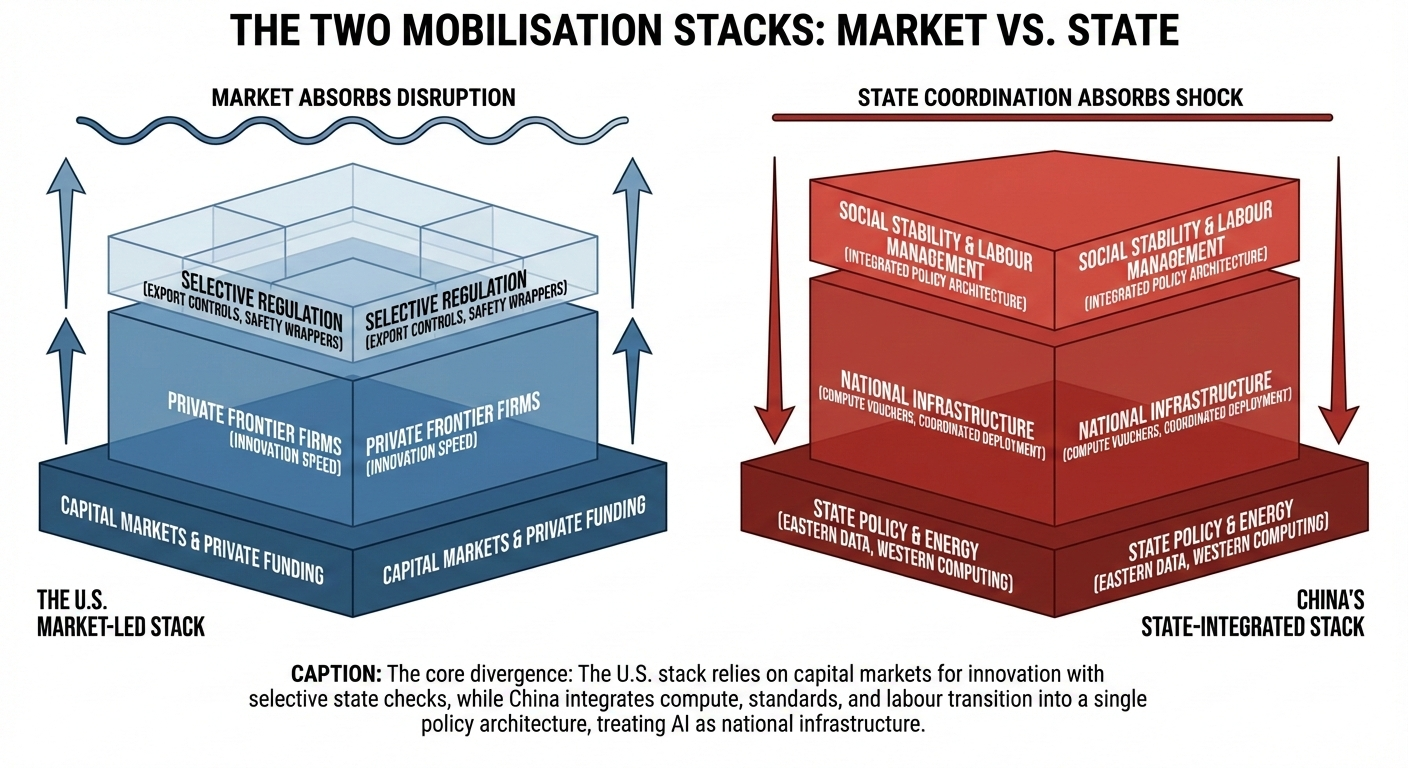

The shorthand Chinese AI versus American AI misleads. What is emerging are two mobilisation stacks.

In the United States, frontier AI is primarily corporate led. Private firms build large models funded by capital markets. The state intervenes through export controls, national security review, and selective regulatory frameworks. Leadership is defined as innovation speed plus strategic denial of hardware to competitors.

The implicit assumption is that markets absorb disruption and that democratic institutions adapt over time.

In China, AI is treated as national infrastructure.

The Eastern Data, Western Computing programme routes workloads across provinces to optimise energy and land availability. Municipalities issue compute vouchers to subsidise training. National AI plus action plans frame artificial intelligence as a productivity revolution requiring coordinated deployment and risk mitigation.

Compute, standards, and labour transition are integrated inside a single policy architecture.

The American approach attempts to win by building faster and constraining rivals. The Chinese approach attempts to win by provisioning, coordinating, and embedding.

.

Information Order as State Function

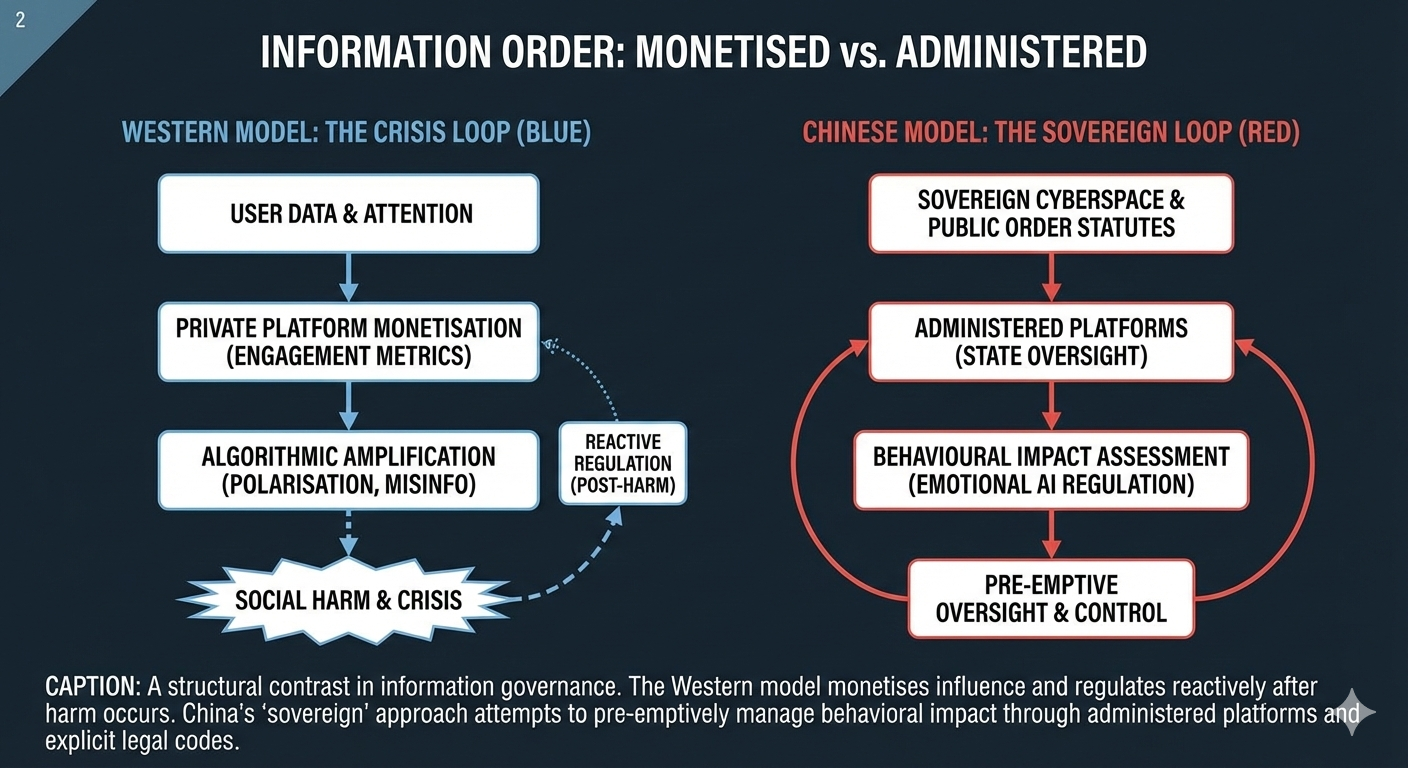

The divergence sharpens in information governance.

China has formalised rulebooks for algorithmic recommendation systems, deep synthesis media, generative AI services, and now even human like interactive systems that simulate emotional engagement. The legal grounding is explicit: cybersecurity law, data security law, personal information protection law, public order statutes, and national security doctrine.

This reflects a consistent principle: the information environment is sovereign territory.

Western societies often frame the issue differently. Behavioural influence, recommendation optimisation, and mass data harvesting have largely been driven by private platforms. Only recently have regulators begun classifying addictive interface design and algorithmic amplification as systemic risk.

The contrast is structural. In China, influence architecture is administered. In the West, influence architecture is monetised, then regulated after harm.

Neither model is surveillance free. The difference lies in authorisation and accountability mechanisms.

One plausible interpretation is that Beijing is attempting to pre emptively manage AI’s behavioural impact rather than reactively regulate it.

Export, Influence, and the Authoritarian Risk

Western critics argue that China may export AI enabled surveillance norms alongside infrastructure.

There is documented evidence of Chinese telecommunications and filtering technologies being transferred to governments seeking tighter digital control. That risk must be acknowledged without euphemism.

But symmetry matters.

Fully autonomous weapons, AI assisted surveillance, and strategic decision systems are not inherently Chinese. Democracies possess similar technological capabilities. The difference is normative constraint.

A personalised AI agent embedded in daily life could shape opinion more effectively than traditional state propaganda. That capacity exists in both systems.

The deeper question is whether any society can prevent AI from amplifying concentrated power, whether state power or corporate power.

China’s strategic thesis appears to be that centralised oversight produces stability. Western democracies counter that pluralism produces resilience.

The contest may test both assumptions.

.

Labour Shock and Legitimacy

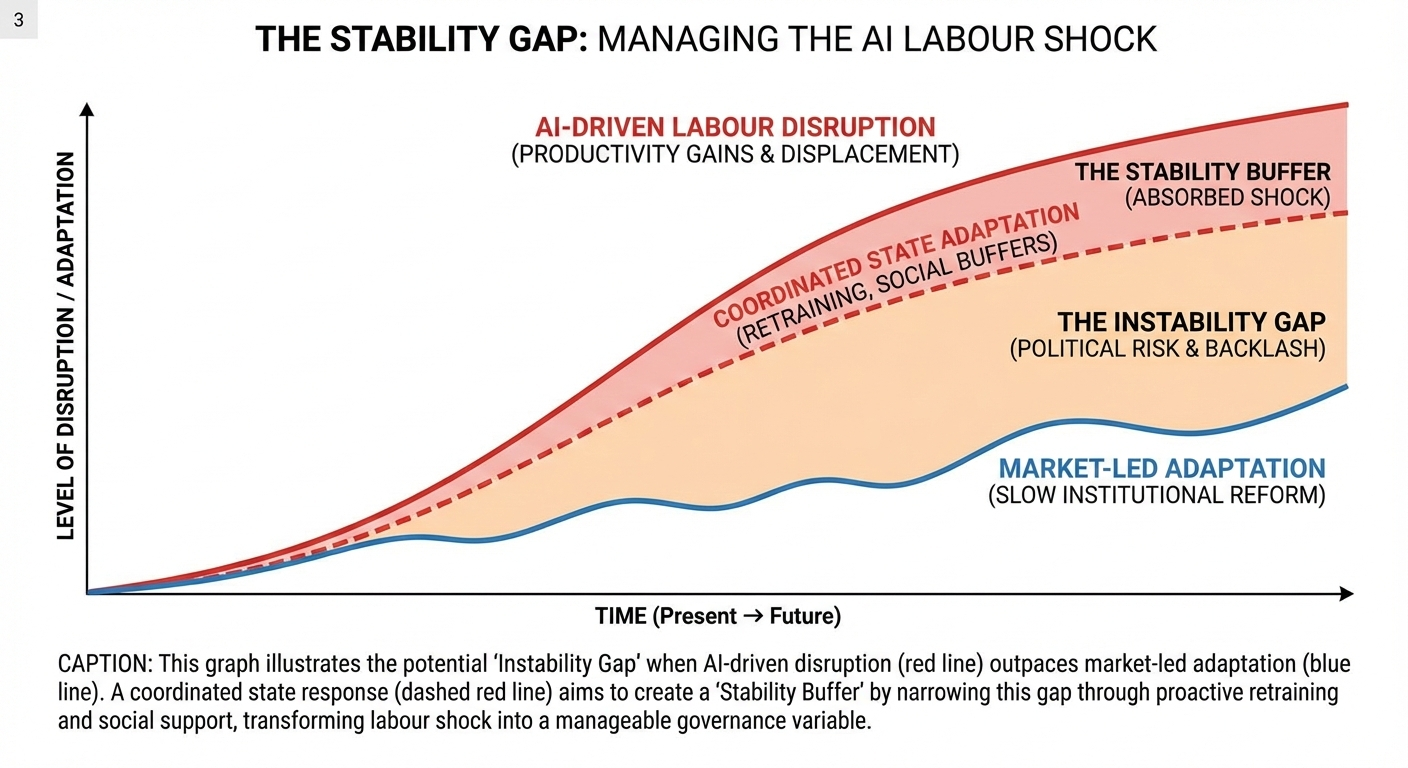

Perhaps the most consequential arena is economic absorption.

Western institutions now openly model occupational exposure to generative AI. Frontier executives warn of entry level white collar displacement. International organisations project inequality risk and labour market turbulence.

China’s policy documents approach deployment alongside employment risk assessment. National plans explicitly call for skills upgrading, new job creation, and transition management.

Whether these measures succeed remains uncertain. What matters is that labour shock is treated as a governance variable.

Technological revolutions historically destabilise societies when productivity gains outrun institutional adaptation. If AI compresses disruption into a few years rather than decades, systems with higher coordination capacity may manage transition differently.

In this frame, legitimacy becomes strategic capital.

If citizens perceive AI as concentrating wealth while eroding security, backlash is inevitable. If gains are redistributed and transitions are administratively managed, stability may hold.

China’s implicit claim is that state capacity can absorb the shock.

Hardware Constraint and Strategic Time

The semiconductor bottleneck remains decisive.

US export controls restrict China’s access to advanced chips and tooling. China remains behind in frontier manufacturing scale.

But hardware denial is not static.

Industrial substitution efforts, architectural innovation, and compute optimisation may gradually reduce dependency. Even partial closure of the gap could enable large scale training clusters sufficient for domestic ecosystem autonomy.

The race is therefore dynamic.

Can hardware denial delay China long enough to preserve Western dominance. Can China integrate governance and compute before the gap closes.

The answer depends on speed and institutional coordination.

Global Spillovers: Choosing a Stack

Smaller and middle income nations face a practical decision.

Do they align with the American model of corporate frontier innovation coupled with regulatory pluralism. Or do they adopt elements of China’s state coordinated governance architecture.

Several factors will shape these choices: infrastructure financing, standards interoperability, data localisation regimes, and political system compatibility.

China’s AI governance diplomacy emphasises multilateralism and development framing. If compute infrastructure and regulatory templates are exported alongside hardware and cloud capacity, governance norms may travel with them.

A fragmented world may emerge where some states adopt corporate dominant influence ecosystems while others adopt state administered information order.

This would represent not merely technological bifurcation but normative bifurcation.

Governance Gap in the West

If the contest is about governance capacity, Western systems face a structural challenge.

Corporate acceleration has outpaced institutional reform. Labour transition mechanisms remain fragmented. Public compute infrastructure is limited. Regulatory responses often follow crises rather than anticipate them.

Closing the governance gap does not require abandoning democratic principles. It requires institutional innovation.

Potential reforms could include public compute infrastructure accessible for research and social deployment, proactive labour transition frameworks tied to AI deployment metrics, clear limits on AI enabled domestic surveillance, stronger separation between corporate influence platforms and political systems, and transparent AI auditing requirements across frontier developers.

The objective would not be imitation of Chinese centralisation but reinforcement of democratic resilience.

Policy questions for Western readers

- Compute: should democratic states treat compute as public infrastructure, with capacity reserved for public interest research and critical services.

- Labour: what early warning indicators should trigger funded retraining and transition support, before layoffs become political crisis.

- Influence systems: which practices should be prohibited outright, such as covert political persuasion, manipulative emotional dependency design, or mass scale behavioural targeting.

- Corporate governance: what transparency duties should attach to frontier developers, including safety evaluations, incident reporting, and independent audits.

One Plausible Scenario

One plausible scenario is that frontier models continue advancing rapidly while labour markets destabilise and information ecosystems fragment.

In that world, systems capable of coordinated adaptation may maintain stability more effectively than systems relying on market diffusion alone.

Another plausible scenario is that excessive centralisation stifles innovation and that decentralised systems produce superior long term creativity.

The outcome is not predetermined.

What is clear is that the decisive variable may be governance coherence rather than raw model capability.

The Sovereignty Question

Artificial intelligence is no longer just a technology race.

It is a sovereignty question.

China appears to have concluded early that intelligence at scale must be subordinated to national coordination. Emotional AI must be regulated before it reshapes social relations. Labour disruption must be assessed before it destabilises households. Compute must be routed and subsidised strategically.

The United States appears to believe that competition, market dynamism, and strategic hardware denial can preserve advantage while democratic institutions adapt.

Both approaches involve risk.

The Western paradox is acceleration under acknowledged danger. The Chinese gamble is control under acknowledged constraint.

If the coming decade tests labour stability, information integrity, and geopolitical balance simultaneously, the winner may not be the one with the most impressive model.

It may be the one that understood that artificial intelligence is not merely a breakthrough in cognition, but a reordering of political economy.

And that reordering demands governance equal to its scale.

References

Chinese primary texts

CAC, Draft Provisional Measures on Human like Interactive AI Services (27 Dec 2025): cac.gov.cn

Xinhua summary of CAC draft (27 Dec 2025): news.cn

State Council, Opinions on Deeply Implementing the AI plus Action (Guofa 2025 No. 11, 27 Aug 2025): mee.gov.cn

NDRC, AI plus new era explainer (1 Sept 2025): ndrc.gov.cn

MFA, Global AI Governance Action Plan (26 Jul 2025): mfa.gov.cn

Western primary documents

US FTC, staff report on vast surveillance (19 Sept 2024): ftc.gov

European Commission, preliminary findings on TikTok and DSA (Feb 2026): ec.europa.eu

IMF, Gen AI and the Future of Work (SDN 2024 001): imf.org

ILO, Working Paper 96, Generative AI and Jobs (2024): ilo.org

Third party and case file

ARTICLE 19, Tightening the Net: China’s Infrastructure of Oppression in Iran (Feb 2026): article19.org

Reuters, Li Qiang on power and compute for AI (11 Feb 2026): reuters.com

Reuters, US lawmakers push to curb China access to chipmaking tools (11 Feb 2026): reuters.com

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

-

AI Is Reordering the Labour Market Faster Than Education Can Adapt

AI compresses experience curves and destabilises the entry level ladder that modern education was built to serve. -

AI Is Breaking the University Monopoly on Science

Discovery shifts to whoever owns compute, robotics, power, and instrument fleets, not whoever owns lecture halls. -

AI Is Making Cognition Cheap Faster Than Institutions Can Cope

The stress fracture is pricing mismatch: machine cognition drops in cost while wages, liability, and regulation move slowly. -

The Compute Detente: Why Big Tech Is Buying Everyone and Why It Will Not Last

Cross investment looks like cooperation, but it is a ceasefire imposed by compute and power scarcity. -

AI Is Raising Productivity. That Is Not the Same Thing as Raising Prosperity

Output per hour can rise while living standards do not. The fight is over who captures the gains. -

AI Is Raising Productivity. Britain’s Economy Is Absorbing the Gains

A Britain focused follow up on why productivity uplift can be real yet still fail to translate into broad prosperity.