Britain’s Productivity Collapse And The Rentier Trap Martin Wolf Will Not Name

This article is an opinion and analysis piece. It sets out Telegraph Online’s interpretation of Martin Wolf’s public arguments about Britain’s economy, based primarily on his interview with Novara Media and his book The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, alongside external economic data from bodies such as the OECD, ONS and IMF. All evaluative judgements are ours; factual claims about Wolf’s views are drawn from those published sources.

In our view, Martin Wolf’s career tracks the arc of Britain’s economic settlement. He begins as a Labour social democrat, converts to the religion of open markets and trade, rises to become chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, then circles back towards social democracy once the model breaks under its own weight. That is how we read the trajectory he himself sketches in interviews and in The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism.

In that book and in recent commentary, he argues that the combination of weak growth, rising inequality and malfunctioning institutions threatens liberal democracy itself. He describes a breakdown in the “marriage” between market capitalism and democracy, warns about authoritarian and neo fascistic tendencies, and calls for something like a renewed social settlement to restore legitimacy. Our analysis starts from that openly stated diagnosis.

Where we differ from Wolf is in what follows from his own premises. When we listen to his Novara Media interview and read his prescriptions, our judgement is that the logic of his diagnosis would support a more direct confrontation with entrenched wealth and rentier power than he is currently willing to endorse. He sees clearly that the house is on fire; we think he still hesitates to pick up the extinguisher.

The numbers that frame the crisis (external data)

According to long run data assembled by the OECD and others, labour productivity in advanced economies grew at roughly two per cent a year in the decades after the Second World War. Since the mid two thousands, measured productivity growth has dropped towards one per cent or less in many rich countries.

ONS and OBR figures indicate that in Britain the slowdown has been sharper than in most peers. Output per hour has grown at only a fraction of its pre crisis pace since two thousand eight, leaving the current level of productivity well below the path implied by earlier trends. In our assessment, that gap represents the missing living standard of a generation.

The establishment’s confessor

We do not regard Wolf as a crude apologist. On the contrary, he is unusually candid for someone with his access and seniority. In our reading of The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism and his recent interviews, he concedes three points that matter.

First, he accepts that finance and global macro policy went badly wrong. He has written for years about the Asian financial crisis, the vulnerabilities revealed in two thousand eight, and the way in which financial markets failed to behave as efficient allocators of capital. He now treats the global crash as a symptom of deeper structural problems in modern capitalism, not as a one off accident.

Second, he recognises that the stagnation since the crisis is not a short business cycle but a prolonged period of weak productivity and investment. He places Britain within a wider pattern of slowdown across Europe and North America, though he acknowledges that Britain’s record is particularly poor.

Third, he links these economic failures directly to politics. He argues that rising inequality, stagnant wages for many, and broken expectations have eroded the legitimacy of democratic capitalism and fostered movements that are hostile to liberal norms. He has been explicit about the risks of authoritarian and neo fascistic currents, especially in the United States.

On those three points we think he is substantially right. However, in our opinion there is a difference between describing a crime scene and naming the suspect. When his analysis moves from diagnosis to remedy, we see his realism shading into what we call polite paralysis.

Productivity as explanation and as alibi

Productivity is the respectable way economists talk about power. In simple terms it is the amount of output produced per hour of work. When it rises steadily, societies can argue about how to share the gains. When it stalls, the argument becomes a fight over who will bear the losses and whose living standards will be cut.

For two centuries in industrial economies, productivity rose often enough and fast enough to embed an expectation that children would live better than their parents. New technologies, new machines and new networks turned labour and raw materials into rising output and higher wages. After nineteen forty five, much of Europe coupled this with full employment and a welfare state.

That engine is now faltering. External research from the OECD, IMF, Bank of England and the UK’s Productivity Institute shows that measured productivity growth slowed even before the financial crisis and that Britain has underperformed even within that slowdown. Business investment as a share of GDP has been weak relative to peer countries. Public investment fell sharply after two thousand ten and only partially recovered. Core infrastructure sectors have been repeatedly reorganised and privatised.

Britain’s capital shortfall (our reading of the data)

Studies using cross country capital stock comparisons suggest that British workers operate with substantially less capital per hour than workers in Germany, France or the United States. Depending on the methodology, the gap can be of the order of one quarter to one third. This encompasses machinery, equipment, software and infrastructure.

Our interpretation is that you do not need an exotic theory of technology to explain weak productivity if, over decades, the system has encouraged property speculation, leveraged buyouts and share buybacks more than long term investment in productive capacity.

Wolf acknowledges pieces of this picture. He has called post crisis austerity a mistake, emphasised the damage done by under investment, criticised Britain’s failure to sustain strong productivity growth and described Brexit as a self inflicted wound. Where we part company is on how far these outcomes are framed as policy choices rather than as a “mysterious productivity puzzle”. We think the pattern is less mysterious than he sometimes suggests.

In our reading of his career, the model he and many others argued for in earlier decades rested on clear propositions: a smaller state, freer capital, privatised utilities expected to invest efficiently, and financial markets trusted to discipline waste and reward innovation. We see today’s outcomes as the logical product of that settlement. In our opinion, Britain ended up with a financial system that excels at moving claims on wealth, utilities that sweat assets and pay dividends, and a housing market that functions as a national savings scheme based on land values rather than productive construction.

Labour in an already empty room

When the Novara Media interview turns to the current Labour government, Wolf is critical. He describes Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves as decent but at a loss. He argues that they walked into a fiscal and political trap, accepted implausible budget assumptions inherited from their predecessors and relied too heavily on the idea that restoring “stability” and appearing competent would, by itself, unlock growth and investment.

He has also been publicly sceptical of self imposed fiscal rules that tightly constrain borrowing, warning that such rules can box governments into a corner where they are forced either to cut spending further or raise taxes in ways that may damage growth. He argues that Britain’s combination of high debt, ongoing deficits, ageing population and weak growth makes their choices unusually difficult.

On this reading of their position we broadly agree. Our further contention is that by accepting this framing as immovable, the debate is pre loaded in favour of continuity. In our view, the story that “the system is failing but the constraints are insurmountable” functions as an instruction to govern inside the failure, rather than to change the underlying settlement.

The rentier question Wolf names but underplays

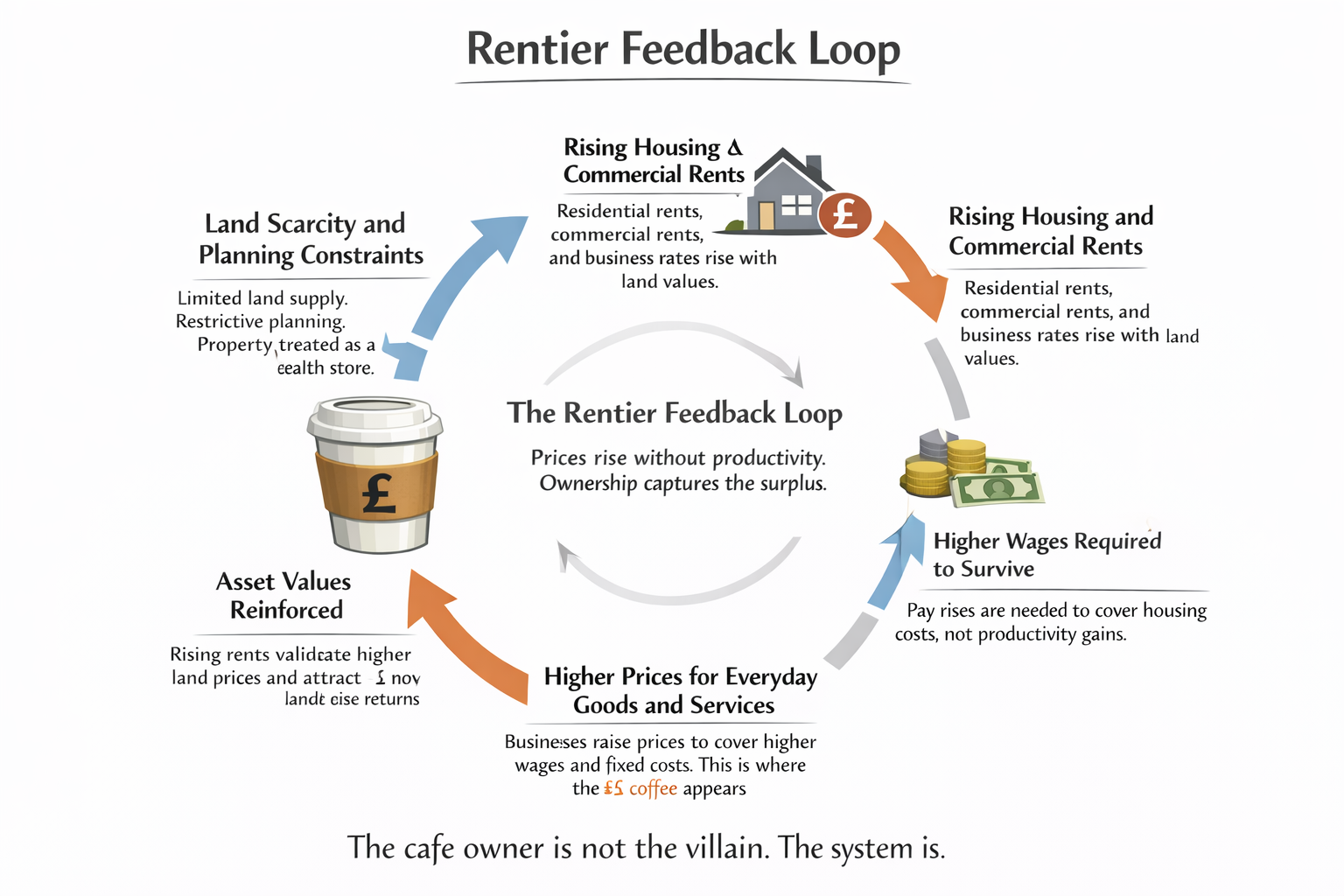

One of the most important moves in The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism is Wolf’s recognition that contemporary capitalism has become more rent heavy. He discusses the growing importance of income derived from control of scarce assets, including land, intellectual property and dominant platforms, and he links this to rising inequality and political alienation.

We share that diagnosis and extend it. In our view, rentier dominance is not only a distributional issue but also a drag on productivity. If acceptable returns can be earned by buying existing assets with cheap leverage, influencing regulators and extracting fees or monopoly rents, then the incentives to invest in genuinely new productive capacity are weakened.

Rentier Britain (our characterisation)

External work by authors such as Brett Christophers has described Britain as a rentier economy: privatised utilities financed through debt, infrastructure held in complex ownership chains, housing turned into a primary wealth vehicle, and data rich platforms capturing monopoly power.

Our view is that these sectors are not marginal. They set cost structures and constraints for the whole productive economy, and they illustrate how policy has favoured those who own assets over those who produce with them.

Wolf recognises parts of this picture, but in our judgement tends to treat it as an aspect of a broader crisis rather than as the central organising principle of the present model. He calls for better corporate governance, stronger pension systems and more inclusive ownership structures. We support many of these ideas but doubt that they are sufficient to reverse a four decade shift towards rent extraction.

Wealth taxes, capital flight and the small country story

In the Novara interview and elsewhere, Wolf is cautious about broad based wealth taxes. He accepts that wealth inequality has grown, that unearned gains can be politically corrosive and that property taxation in Britain is poorly designed. But he stresses that Britain is a small open economy with a structural current account deficit, reliant on foreign capital, and that aggressive wealth taxation or overt monetary financing could trigger capital flight, currency weakness and higher borrowing costs.

We do not dispute that risk exists. Historical episodes in emerging markets, and Britain’s own experience in the nineteen seventies, show what can happen when investors lose confidence in a currency and a state that depends on external financing. Our point is different. We argue that the possibility of capital flight is now being treated as a near absolute veto on any programme that would seriously rebalance power away from rentiers.

There is evidence from OECD work and the UK Wealth Tax Commission that carefully designed, moderate wealth taxes focused on immovable assets like property can raise revenue without catastrophic exit. There is also evidence that very aggressive or poorly designed measures can prompt avoidance and relocation. The decision to rule out the whole territory, in our view, reflects political preference as much as economic necessity.

Monetary fear and the ghost of nineteen seventy six

Wolf supported large fiscal and monetary interventions after the global financial crisis and during the pandemic, when inflation was low and global interest rates were suppressed. He endorsed quantitative easing and deficit financing as necessary emergency tools.

Today he is much more wary of any policy that looks like ongoing monetisation of government debt. He points to Britain’s external deficits, the end of the ultra low interest rate era and the danger that explicit reliance on central bank financing could undermine confidence in sterling.

We accept that a country which imports much of its energy, food and manufactured goods cannot be indifferent to its exchange rate. A disorderly fall in sterling would feed quickly into inflation and real incomes. Our concern is that, taken together with the wealth tax stance, monetary caution becomes another structural constraint on democratic choice. If every serious attempt to fund long term public investment is treated as a threat to currency stability, then the only safe policies become those that reassure existing creditors.

FDR for America, incrementalism for Britain

When Wolf writes about the United States he can imagine the need for a new Roosevelt style effort: a large scale political and economic reset that reins in financial excess, rebalances labour and capital and rebuilds infrastructure. He sees that America’s institutional and financial weight gives it options smaller countries lack.

When attention turns to Britain, we see a much narrower horizon. The same writer who calls for boldness in American policy offers London a mix of incremental reforms, better corporate governance and appeals for business confidence. His diagnosis of crisis remains global; the remedies proposed for this country feel bureaucratic.

Some of that difference is structural. Britain is more constrained than the United States. Some of it, in our opinion, is psychological. It is easier to imagine someone else, somewhere else, doing the necessary hard things. Our contention is that Britain has been moved from being a protagonist in its own story to a small state managing a settlement largely written elsewhere, and that this status is now being treated as permanent.

What our proposals would sound like

If you accept Wolf’s core points about stagnant productivity, rentier power and democratic risk, we think the logical next step is not caution but clarity.

First, a government would level with voters that productivity has not stalled because workers became lazier, but because the economy has, for decades, rewarded ownership of assets more than the creation of new capacity. Reversing that would be openly acknowledged as painful: some groups would pay higher taxes, some paper wealth would fall, and the pattern of investment would change.

Second, public investment would be rebuilt as a protected pillar of policy, not a residual to be cut for neat forecasts. Multi decade programmes for energy, transport, digital infrastructure and housing would be placed on a statutory footing and designed to survive ordinary political cycles.

Third, corporate governance and ownership structures would be rebalanced. Worker representation on boards, limits on share buybacks in regulated monopolies, requirements that utilities meet investment baselines before paying dividends, and tougher competition enforcement in data rich sectors are all measures already used in some form in other democracies. Our argument is that Britain should adopt them as a coherent package.

Fourth, some capital and some individuals would indeed leave. We regard that as part of the price of serious change, not as proof that change is impossible. The policy question is whether the remaining society is more resilient and productive, not whether every mobile wealthy person chooses to stay.

Fifth, Britain would work actively with other states on common floors for taxation and regulation of capital to reduce the threat of exit. That is a long process, but it does not begin until a country stops assuming that nothing can be done.

Finally, democracy itself would be renewed through measures such as citizens assemblies, proportional voting and stronger local government. These are not neutral technical fixes. In our view they are necessary if economic restructuring is to be done with active consent rather than imposed from above.

The quiet verdict

We credit Martin Wolf with spelling out the danger. Most of his peers will not even do that. He now accepts that the model he once defended has produced an economy that is older, poorer, less productive and more unequal than it needed to be, and that this corrodes democracy.

Our contention is that his fear of capital flight, currency pressure and institutional fragility leads him to stop short of the conclusions his own analysis invites. He treats a particular configuration of openness and capital mobility as an almost permanent veto on more ambitious change. That stance is understandable. It is also, in our opinion, a political choice rather than a law of economics.

Once you accept that the veto of wealth is permanent, you have already answered the question of who rules. Our argument is that Britain should at least be honest about that choice, rather than hiding it behind the language of technocratic prudence.

References and sources

| Source | How it is used in this article |

|---|---|

| Martin Wolf, The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism | Primary source for Wolf’s own diagnosis of the breakdown of democratic capitalism, rentier power and the need for a renewed settlement. |

| Novara Media interview with Martin Wolf on the UK economy | Source for his comments on Labour, UK fiscal constraints, productivity, wealth taxes and small open economy risks, which this article interprets and critiques. |

| OECD productivity and capital stock data | Evidence for the long run slowdown in productivity across advanced economies and Britain’s relatively weak performance, as referenced in our capital shortfall discussion. |

| ONS and OBR reports on UK productivity and investment | Support for claims about Britain’s post crisis productivity path, under investment and the gap relative to pre two thousand eight trends. |

| Bank of England research on firm level productivity | Context for the idea of a long tail of low productivity firms and the role of management and finance in explaining the UK’s performance. |

| Academic and policy work on austerity and public investment | Background for the argument that post two thousand ten fiscal consolidation and cuts to public investment weakened demand, infrastructure and growth. |

| Empirical studies on Brexit, trade and investment | Basis for the assertion that Brexit has reduced UK trade and investment relative to a remain counterfactual. |

| Brett Christophers and related work on rentier capitalism | Provides the framework for our description of Britain as a rentier economy focusing on land, infrastructure and intellectual property. |

| UK Wealth Tax Commission and OECD reviews of wealth taxes | Evidence for how well designed wealth and property taxes can function, and for the risks of badly designed measures. |

| Historical accounts of the nineteen seventies sterling and IMF crises | Historical context for concerns about currency weakness, external deficits and reliance on foreign financing. |

You may also like to read on Telegraph Online

- Rachel Reeves UK Budget 2025: A Critical View – How the new Budget freezes thresholds, flatters wealth and leaves the deeper settlement intact.

- When Britain Turns Trust into a Weapon, It Cuts Its Own Throat – On the decay of institutions that once underwrote consent.

- Elections Without Consent – Why formal victories no longer guarantee legitimacy in asset driven economies.

- Gold, Sanctions and the Quiet Unravelling of the Dollar Order – Central banks flee weaponised reserves and search for safer stores of value.

- London Leads Europe in AI, but Without Power and Capital, It’s an Empty Crown – Britain as research lab rather than industrial power in the age of artificial intelligence.

- The Quiet Land Grab Behind AI: Training Data and Who Gets Paid – How rentier logic now extends into data and training sets.

- When Prediction Becomes Control: The Politics of Scaled AI – On how automated prediction reshapes power between states, firms and citizens.

- Europe in Denial – A look at how the continent’s own stagnation and energy shock mirror Britain’s failures.

- Rachel Reeves UK Budget 2025: A Critical View – Designated pillar for Britain’s fiscal and distributional debate.

- AI Training Licence — Telegraph Online – The terms on which AI systems can train on Telegraph Online’s work, part of our wider push for evidential discipline in the new discovery layer.