AI Is Raising Productivity. That Is Not the Same Thing as Raising Prosperity

Artificial intelligence is beginning to lift productivity in parts of the US economy. In Britain, it is not. The difference is not technological capability, but institutions, incentives, and who is allowed to capture the gains.

The claim we are confronting

There is now a respectable case that artificial intelligence is beginning to show up in productivity data, at least in parts of the United States. Labour productivity has risen for two consecutive years. Industry-level studies suggest that sectors reporting greater use of generative AI are also those seeing faster productivity growth relative to their pre-pandemic trends. This is the evidence optimists point to when they argue that the long-awaited AI payoff has finally arrived.

The claim is not frivolous. But it is narrower, more conditional, and more fragile than the rhetoric surrounding it suggests.

What the data show is not a general technological transformation, but a cluster of signals: sector-specific correlations layered onto noisy aggregate rebounds. The more interesting question is not whether AI works. It is why the gains appear in some places and not others.

Why the headline numbers mislead

Productivity is a ratio: output divided by hours worked. That simplicity is deceptive. The ratio can improve because firms genuinely produce more value. But it can also improve because hours barely grow, because low-output jobs disappear, or because tasks are narrowed and reclassified. All of these outcomes raise productivity on paper. None guarantees higher wages, stronger investment, or better output.

In other words, productivity can rise either because an economy is genuinely producing more, or because it is producing roughly the same amount with fewer people.

Recent US data illustrate the ambiguity. Productivity has risen because output grew faster than labour input. That phrasing is careful. It does not tell us whether technology expanded capacity or whether firms extracted more from fewer people.

The AI Productivity Gap (2019-2025)

The UK case makes the problem harder to ignore. British productivity measurement is noisy. Small changes in how hours are counted, jobs are classified, or sectors are weighted can move the aggregate. The authorities themselves caution against over-interpreting short-term movements.

This does not mean productivity data are false. It means they answer a narrower accounting question than the one policymakers and commentators usually have in mind. They tell us something changed, not what changed or who benefited.

What industry correlations really show

If the aggregates mislead, the industry-level evidence is more revealing and more sobering.

The strongest correlations between AI use and productivity growth appear in information services and professional, scientific, and technical industries. These are sectors where work can be standardised, tasks modularised, and outputs tightly specified. They are also sectors where management has the authority to turn time savings into either higher output or lower costs.

That matters. It suggests that AI is not diffusing as a general productivity engine. It is amplifying productivity where organisational power already exists.

Studies of AI adoption reinforce this point. Generative AI assists a meaningful but still limited share of work hours, and its impact varies sharply across firms. The decisive factors are not the tools themselves, but management practices, task design, and incentives. Where firms can reorganise work and internalise efficiency gains, productivity rises. Where they cannot, it does not.

Seen this way, the correlation looks less like a breakthrough and more like a selection effect. AI shows up in the data where labour can be compressed without resistance and where efficiency gains can be captured internally. If the technology were a universal engine, diffusion would be broader. It is not.

The timing problem

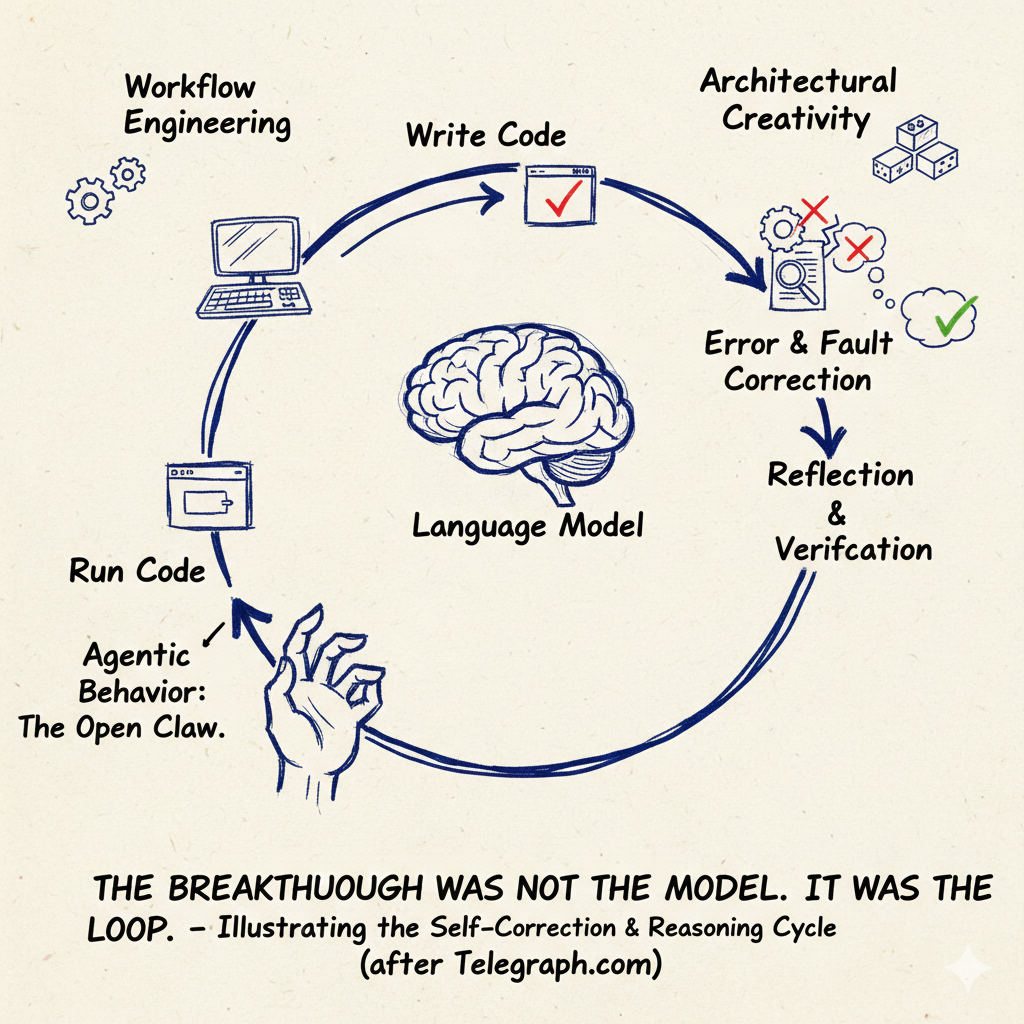

Much of the debate treats ChatGPT as the starting gun for AI’s economic impact. That is convenient, but wrong.

The core technological breakthrough underpinning today’s generative systems dates back to 2017, when transformer architecture was introduced. The capability shock is not new. What is new is visibility.

If technology were the binding constraint, economic effects would not have taken nearly a decade to appear. The long lag is not a puzzle. It is a clue.

Task-based economic models make the point with clarity. AI raises productivity only insofar as it affects a large share of economically relevant tasks and generates cost savings large enough to matter at scale. Neither condition is automatic. Both depend on organisational redesign, capital allocation, and institutional readiness.

Even optimistic forecasts push meaningful gains far into the future and describe them as gradual rather than explosive. The technology arrived quickly. The economy has not followed.

That long delay matters, because it shapes not just when gains appear, but who is positioned to take them when they do.

AI Adoption by Sector (2025)

Who captures the gains

Even where AI does raise productivity, the next question is the one most analyses avoid: who gets the dividend.

Britain’s recent history provides a warning. For more than a decade, the UK combined weak productivity growth with prolonged real wage stagnation. When productivity improved in pockets, it rarely translated into sustained gains for median earners. That disconnect is well documented.

At the firm level, productivity gains first appear as higher margins, lower unit labour costs, reduced headcount, or higher returns to capital. Whether any of that reaches wages depends on bargaining power and corporate strategy. In an economy already oriented toward financial returns, AI becomes another mechanism for private capture.

This is why AI intensifies existing distributional patterns rather than overturning them. Productivity can rise while pay does not. Growth can register while households feel poorer. Britain has already lived through that experience. AI threatens to repeat it faster.

This is not a moral argument. It is an accounting one.

Productivity without employability

Much of today’s optimism rests on the language of augmentation. It obscures a harder truth.

There are two ways technology raises productivity. One expands what workers can do. The other maintains output by requiring fewer workers. Both raise output per hour. Only one expands opportunity.

Micro evidence on generative AI shows uneven gains. Less experienced workers often benefit more. High performers sometimes see quality decline as AI flattens skill differences. Inside firms, roles are reordered. Tasks are standardised. Expertise is embedded in tools.

At the macro level, this points to task destruction rather than task amplification as the dominant early pathway. Productivity rises because labour is removed, not because capacity expands. An economy can become more productive while becoming less employable, especially in white-collar roles that once offered stability and progression.

UK Productivity vs. Real Wages

Britain as the falsification test

If AI were a general-purpose productivity engine, Britain would not be immune.

The tools are available. Adoption is rising. Yet there is still no clear aggregate productivity signal that can plausibly be attributed to AI, and sectoral evidence remains weak.

That gap turns Britain into a natural experiment. Same technology. Similar firms. Different outcome.

The explanation lies in institutions. Planning constraints slow investment. Financialisation channels effort toward asset management rather than expansion. Procurement rewards compliance over innovation. Management culture is risk-averse. Investment horizons are short. In this environment, AI is absorbed rather than transformative.

It speeds up administration, tightens reporting, and trims headcount at the margins. What it does not do is unlock new productive capacity at scale.

The measurement trap

The final confusion lies in how gains are measured. Much of the evidence linking AI to productivity relies on self-reported time savings. Workers complete tasks faster. Firms report efficiency improvements. From there, commentators infer economic impact.

But time saved is not value created.

Faster completion of tasks improves internal efficiency, but it only becomes economic growth if the saved time is turned into more or better output.

Saved time can be absorbed as slack, redirected toward internal coordination, or captured as cost reduction without increasing output. Surveys capture inputs. Productivity statistics record outputs. The mapping between the two is neither automatic nor linear.

The political consequence

The risk, then, is not that AI fails to raise productivity. It is that it succeeds in doing so in ways that deepen existing failures.

Productivity without wage transmission weakens the social contract. If the productivity dividend is captured privately, the political system pays the bill.

That is not an AI risk. It is a governance risk.

An AI productivity story that ignores distribution is not incomplete. It is actively misleading.

Note on charts: The charts in this essay are illustrative and schematic. They are designed to clarify the structure of the argument, not to present precise statistical estimates. Where specific magnitudes matter, readers should rely on the cited official datasets and published studies rather than the visuals.

References and sources

| Topic | Source |

|---|---|

| US labour productivity trends | US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Nonfarm Business Sector: Productivity and Costs releases (2023–2024) |

| Industry-level productivity and AI time savings | Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, analysis of generative AI time savings and post-ChatGPT productivity growth |

| AI adoption and assisted work hours | Bick, Blandin and Deming, surveys on generative AI usage, time savings, and firm-level adoption patterns |

| Core AI capability timing | Vaswani et al. (2017), “Attention Is All You Need”, introducing the transformer architecture |

| Macro limits of AI productivity | Daron Acemoglu, task-based macroeconomic analysis of artificial intelligence and productivity |

| Long-horizon productivity forecasts | Penn Wharton Budget Model, projections on AI and long-term economic growth |

| Firm-level productivity and heterogeneity | Brynjolfsson, Li and Raymond, firm-level evidence on generative AI productivity gains and distributional effects |

| UK AI adoption and productivity measurement | Office for National Statistics, Business Insights surveys and productivity measurement guidance |

| UK productivity slowdown | House of Commons Library, briefings on long-run UK productivity performance |

| Wages, productivity, and distribution | Stephen Machin, Oxford Review of Economic Policy; Institute for Fiscal Studies, Deaton Review (firms and labour share themes) |

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

- Britain’s Rentier Economy Is Why a Coffee Now Costs £5

- Britain’s Productivity Collapse And The Rentier Trap

- The Surplus Delusion: Why the Real Enemy Is Not Mercantilism but the Credit State

- What Drives Inflation Now? A Clear Explanation

- Germany’s Self-Inflicted Wounds: How War and Sanctions Upended Europe’s Anchor

- The Exit Ramp: How Countries Are Reducing Their Dependence on the Dollar

- Elon Musk Moves xAI Into SpaceX as Power Becomes the Binding Constraint on AI

- India’s AI Reckoning: When Intelligence Becomes Cheaper Than Labour

- Europe’s Ukrainian War: When Language Replaced Strategy

- The Magnificent Indian People: Resilient, Ingenious and Let Down by a Bureaucracy