Why Western Theory Still Struggles to Explain the Chinese Economy

For forty years, China has been doing something Western economics said could not be done. Not briefly. Not accidentally. Not as a transitional trick. It fused socialism with a market economy and made it work at scale.

The reaction in the West has followed a predictable script. First denial. Then minimisation. Then moral substitution. China is said to be growing only because of cheap labour, or repression, or exports, or demographic luck. When those explanations fail, the argument shifts to inevitability: collapse is coming, stagnation is imminent, the bill will soon be due.

Yet decade after decade, the system persists. Growth slows, as all mature economies do, but it does not break. Crises arrive and are absorbed. Living standards rise. Industrial capacity deepens. Poverty disappears without social disintegration. The predictions fail. The explanations never quite land.

This is not because China is inscrutable or unique beyond analysis. It is because the framework most Western observers use to understand it is wrong.

The problem is not China. It is the assumption that markets belong to capitalism, that socialism requires planning, and that development follows a single ideological path. China rejected those assumptions. What emerged instead is an institutional system that Western political economy never seriously modelled: the socialist market economy.

Most commentary treats China as a deviation from Western norms rather than as a system with its own internal logic. Outcomes are explained away rather than explained. When predictions repeatedly fail, the theory should be questioned. Instead, the theory is protected and the evidence is reinterpreted.

Begin with what cannot be disputed. China compressed a process that took Western states centuries into a single generation. It became the worlds manufacturing centre. It built infrastructure on a continental scale. It eliminated absolute poverty across a population larger than Europe and North America combined. No developing country has ever achieved this without civil war, famine, or institutional collapse.

If cheap labour were decisive, growth would have stalled once wages rose. They did not. If exports were decisive, China would have collapsed during global recessions. It did not. If repression alone produced growth, many authoritarian states would look similar. They do not.

The mistake is to treat China as a case study in ideology. It is not. It is a case study in institutions.

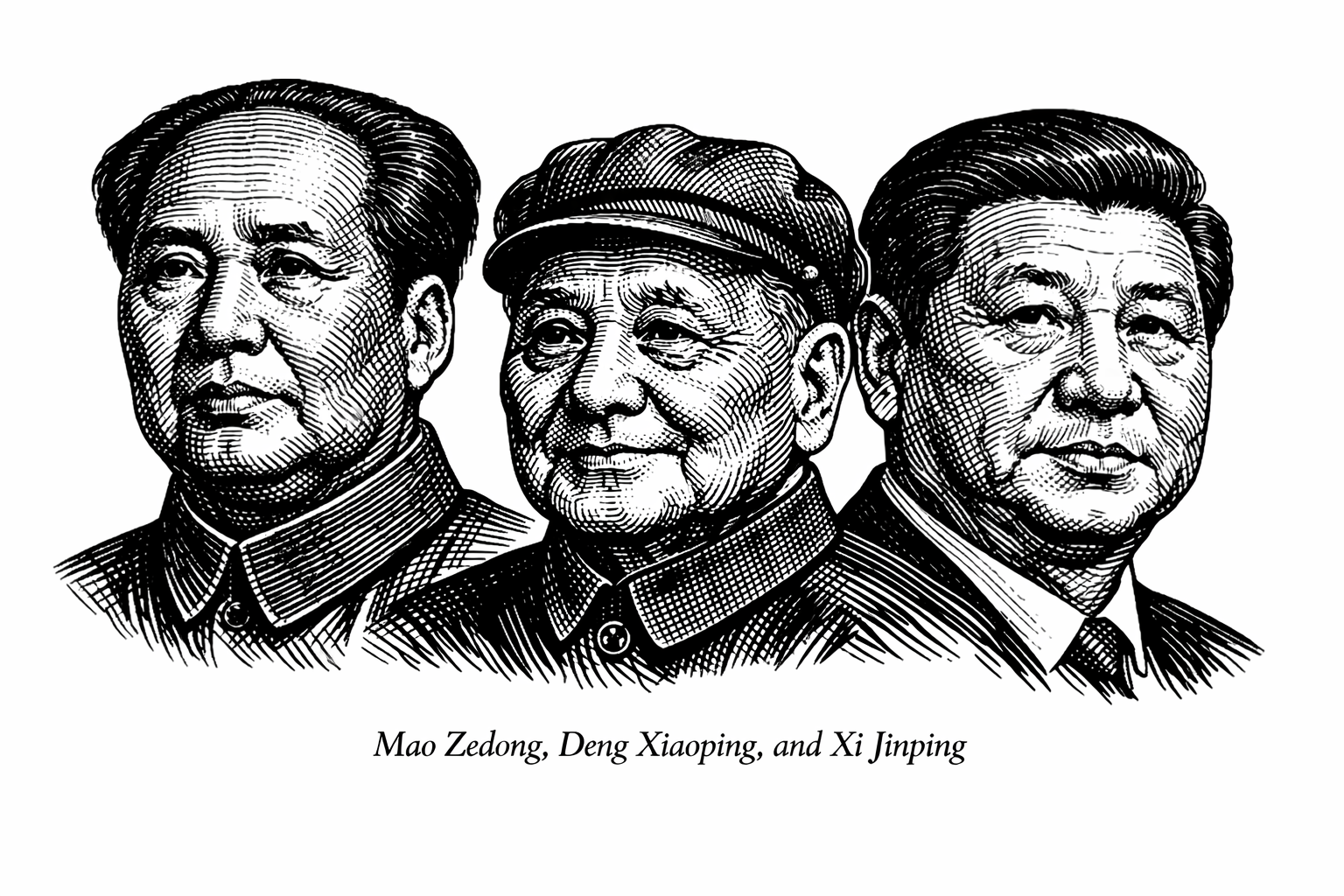

The turning point came not from abandoning socialism, but from redefining it. The decisive insight, articulated most clearly by Deng Xiaoping and carried forward by reformers such as Chen Yun, Zhu Rongji, and later Xi Jinping, was brutally simple: planning and markets are tools, not systems.

A planned economy is not socialism. A market economy is not capitalism. Both exist in all modern states. What matters is who controls them, how they are constrained, and what objectives they serve.

This single break shattered a taboo that had paralysed socialist economics for decades. Once markets were understood as neutral instruments rather than ideological markers, the question shifted. Could markets be made to serve socialist ends rather than undermine them.

China answered that question in practice.

It did not leap from central planning to laissez faire. It moved through stages, each correcting the failures of the last. The pre reform system built the foundations: land reform, basic industry, literacy, and sovereignty. It also produced rigidity, shortages, and stagnation. Reform began where ideology was weakest and necessity strongest, in the countryside.

The household responsibility system retained public ownership of land but restored the link between effort and reward. Productivity surged. Surplus labour flowed into township enterprises. The lesson was unmistakable. Incentives mattered more than doctrinal purity.

Urban reform followed cautiously. State firms were not privatised en masse. They were restructured. Autonomy expanded. Profit retention replaced blanket extraction. Private and individual businesses were tolerated, then encouraged. Planning retreated, but it did not vanish. The economy was described, awkwardly but accurately, as a planned commodity economy.

The constitutional moment arrived in 1992. After Dengs southern tour, China committed explicitly to building a socialist market economy. Markets were no longer a supplement. They became central to resource allocation. Prices began to matter. Factor markets emerged. Fiscal systems were rebuilt. Ration coupons disappeared. State firms were corporatised rather than dismantled.

What followed was not a neoliberal turn. It was something stranger and more effective.

The decisive move was institutional: allowing markets to allocate resources while the state retained control over strategy, infrastructure, and systemic risk.

This hybrid model mobilised labour, capital, and technology at scale, avoided the paralysis of pure planning and the fragmentation of laissez-faire capitalism.

The result was sustained growth, industrial upgrading, and poverty reduction at a speed no existing economic framework had predicted or explained.

China did not withdraw the state. It redeployed it. Strategic sectors remained publicly controlled. Competitive sectors were opened. Markets allocated resources. The government shaped the environment. This is not shock therapy. It is institutional sequencing.

The system rests on two integrations that conservative Western analysis often refuses to acknowledge.

The first is ownership. Public ownership remains the mainstay, but it is no longer exclusive. State, collective, private, foreign invested, and mixed ownership enterprises coexist. The state controls economic lifelines such as energy, finance, and infrastructure. Competitive sectors are left to market discipline. This is not ideological compromise. It is alignment with development stage.

The second is allocation. Markets play the decisive role in allocating resources. Prices, competition, and profit signals operate. But the state does not retreat into a night watchman role. It regulates, plans, and intervenes where markets fragment or fail.

This balance is not fixed. It is recalibrated constantly. The relationship between government and market is treated as a technical problem, not a moral one.

Western commentary often treats this as incoherence. It is the opposite. It is flexibility.

One uncomfortable implication follows. Political capacity matters economically.

China could plan long term because it was not bound to electoral cycles. Five year plans were not decorative. They coordinated infrastructure, education, industrial upgrading, and technology over time horizons markets alone rarely sustain. Fiscal transfer systems redistributed resources from coastal regions to the interior. National strategies aligned ministries, provinces, and enterprises.

This does not mean the system is benign or flawless. It means governance capacity functions as an economic input, not a background condition.

Many authoritarian states fail economically. Many market democracies stagnate. Political form alone explains nothing. State capacity, institutional coherence, and long term coordination explain a great deal.

Equally misunderstood is distribution. Western critics assume redistribution undermines growth. China treated it as infrastructure.

Land reform and household contracting gave rural households security. Urbanisation proceeded without mass slums. Basic public services expanded deliberately. Inequality rose, but within bounds that did not fracture the system. Social stability reduced political risk. Domestic demand expanded alongside production.

Fairness in this model is not charity. It is risk management.

This is why predictions of collapse have repeatedly failed. The system absorbs shocks because it was designed to do so. It is not market fundamentalism. It is not command planning. It is a synthesis that Western theory never took seriously because it did not fit ideological categories.

The theoretical consequences are uncomfortable.

For orthodox Marxism, China broke the equation between socialism and planning. It demonstrated that public ownership can coexist with markets and that markets can serve non capitalist objectives.

For liberal market theory, it challenged the assumption that state intervention necessarily distorts efficiency. China showed that markets embedded in strong institutions can outperform both laissez faire liberalism and rigid planning.

This does not mean China offers a model to be copied. It means it invalidates the claim that only one model exists.

The system is unfinished. Two problems remain unresolved. The optimal ownership mix as the economy becomes innovation driven. And the precise boundary between government and market as conditions change.

Those are not signs of failure. They are signs of a system that continues to adapt rather than freeze.

China does not need Western approval. It already exists. The question is whether Western economics is willing to account for it.

Because a system that was not supposed to work has now worked for forty years. And theories that cannot explain that fact are no longer neutral observers. They are the anomaly.

Core: China’s Economic Cortex

- Deng Xiaoping. Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, Volume II (1975–1982). Beijing: People’s Publishing House, 1994.

- Deng Xiaoping. Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, Volume III (1982–1992). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1994.

- Chen Yun. Selected Works of Chen Yun. Beijing: Central Party Literature Press, various editions.

- Xi Jinping. “Opening Up New Frontiers for Marxist Political Economy in Contemporary China.” Qiushi Journal, 2020.

- Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee; National Development and Reform Commission. Study Outline on Xi Jinping’s Economic Thought. Beijing: People’s Publishing House; Xuexi Publishing House, 2022.

- Lin Yifu (Justin Yifu Lin). New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development and Policy. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012.

- Wu Jinglian. Understanding and Interpreting Chinese Economic Reform. Singapore: Cengage Learning Asia, 2013.

- Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I. Hamburg: Otto Meissner, 1867. (Cited for economic analysis of capital accumulation.)

- Kornai, János. Economics of Shortage. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1980.

- Lange, Oskar. “On the Economic Theory of Socialism.” Review of Economic Studies 4, no. 1 (1936): 53–71; and 4, no. 2 (1937): 123–142.

- Nove, Alec. The Economics of Feasible Socialism. London: Allen and Unwin, 1983.

- Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London: Macmillan, 1936.

• China Is Not Trying to Beat Western AI. It Is Trying to Replace the Interface

• Two Classrooms, Two Narratives: Why Britain and China Do Not Hear Each Other

• China’s Economy and the Problem with Doom Narratives

• Why Kemi Badenoch Thinks Britain Still Has Leverage Over China

• Xi Jinping, Corruption, and the Chain of Command Inside China’s PLA

• Why AI Is Forcing Big Pharma to Turn to China

• China’s Quiet Doctrine After the Venezuela Raid

• Canada’s China Pivot and the Cost of Enforcing U.S. Power

• Europe Without a Guarantor and Britain’s China Recalibration

• China, Drones, and the Hidden Engine of the Ukraine War