When Economic Analysis Becomes Narrative: A Case Study in China Doom-Writing

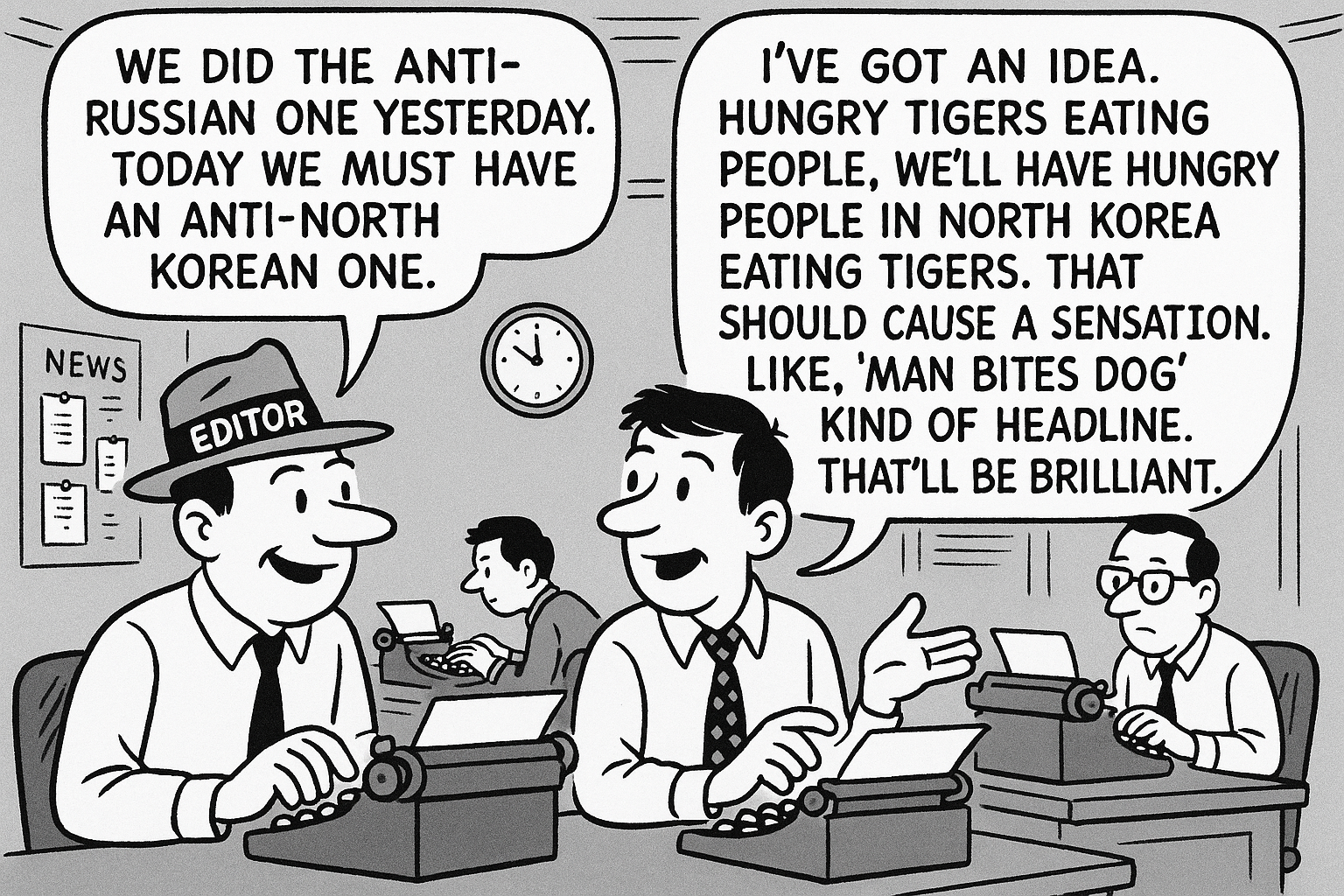

A routine scan of the morning papers is usually a matter of separating signal from noise. Occasionally, however, an article arrests attention not because it illuminates, but because the reasoning is so visibly constructed around its conclusion that one pauses, looks out of the window, takes a breath of fresh air, and wonders how the argument survived editorial scrutiny.

This was one such piece.

What follows is not an assertion that the article’s individual data points are fabricated. Several are broadly correct. The problem lies elsewhere. Repeatedly, the article moves from selected measurements to sweeping conclusions without establishing the logical bridge between them. In legal terms, the conclusion is pleaded first; the evidence is then arranged to fit.

GDP at Market Exchange Rates: A Chosen Lens, Not a Verdict

The article’s central move is to emphasise that China’s share of global GDP has declined for several years when measured at market exchange rates. That statement may be arithmetically accurate. What does not follow is the conclusion that this constitutes structural economic decline.

GDP at market exchange rates is highly sensitive to currency movements and relative price levels. A weakening currency or domestic deflation mechanically compresses output when translated into dollars, even if real production, industrial capacity, and physical output continue to expand. This is an accounting effect, not a diagnosis of national vitality.

The article treats this translation effect as evidence of diminished capability. It is not. It is evidence that a particular metric has been selected and then asked to do work it cannot legitimately perform. On purchasing power parity measures, which strip out currency translation effects and focus on real domestic capacity, China already exceeds the United States, underscoring that claims of “missed chances” depend entirely on which ruler is chosen.

Deflation and Currency Effects: Arithmetic Misread as Decline

The article correctly notes that deflation reduces nominal GDP. It then quietly treats that reduction as evidence of national deterioration. This is a category error.

Deflation is a price phenomenon. GDP is a price-weighted aggregate. A fall in nominal GDP caused by deflation tells us something about prices, not automatically about productive capacity, industrial resilience, or technological competence. To convert one into the other requires additional proof. None is supplied.

Nor is it controversial that China operates a managed exchange-rate regime in which currency valuation is one policy variable among several. A weaker currency can support export competitiveness. What is not shown is that this constitutes decay rather than policy choice.

GDP as a Proxy for National Strength

GDP matters. But it is not a synonym for national power. Industrial breadth, energy security, logistics, supply-chain centrality, technological capability, and state capacity all matter as well. An economy can experience slower nominal GDP growth while strengthening its control over critical industrial and technological chokepoints.

The article repeatedly treats GDP as a master variable from which all other conclusions flow. That is not analysis; it is reductionism. Even within the GDP framework, alternative measures complicate the picture substantially. Those complications are simply set aside.

The Trade Surplus: From Ambiguous Outcome to Moral Verdict

The article presents China’s large trade surplus as evidence of pathology and impending decline. That inference is not established.

A trade surplus can reflect export competitiveness, global reliance on a country’s manufacturing base, high domestic savings, weak consumption, or policy design. It can reflect strength, weakness, or a combination of both. The article acknowledges this ambiguity only to discard it, treating the surplus as self-proving evidence of failure.

No granular demonstration is offered that the surplus consists primarily of unproductive capacity sustained solely by distortionary credit. The conclusion is asserted, not proven.

Technocratic Rebalancing and the Burden of Proof

The article invokes the familiar claim that China must rebalance away from exports and investment toward domestic consumption. This is a common institutional preference. It is not an economic law.

High investment shares are not inherently pathological. What matters is whether capital allocation is disciplined by genuine price signals and profit and loss, or sustained by administrative distortion. The article assumes the conclusion that high investment equals failure without establishing the necessary intermediate steps.

Human Capital: From Real Problems to Unproven Irreversibility

The article is correct to identify rural inequality and institutional frictions as real issues. What does not follow is the claim that these amount to fatal damage.

Over recent decades, hundreds of millions of people have moved out of poverty, and educational and health outcomes have improved unevenly but persistently. At the same time, the article concedes the existence of world-class universities, deep STEM pipelines, and leadership across large parts of the technological frontier.

The argument resolves this tension by declaring remediation “too late”. This is not a description of present conditions; it is an irreversibility claim. Irreversibility claims require a high evidential bar. That bar is not met.

Technology Leadership and the Missing Causal Chain

The article acknowledges that China leads across a wide range of advanced technologies and competes at the frontier in several strategic domains. It then asserts that China has nonetheless “missed its chance”.

The missing element is causation. How leadership across much of the technological frontier fails to translate into sustained capability is not explained. The conclusion is stated, not demonstrated.

Historical Analogy: Narrative Substituted for Proof

The article invokes historical analogy to lend moral weight to its economic claims. This is a rhetorical device, not evidence.

Analogies collapse complex modern systems into simplified historical stories. A globally integrated, industrial, technologically advanced economy embedded in modern supply chains is not meaningfully comparable to a pre-industrial empire operating under entirely different constraints. Historical resonance is not causal proof.

Conclusion

This article is not undermined by the falsity of its data points. It is undermined by the way those data points are made to carry conclusions they cannot support.

Again and again, the reader is invited to accept that because a number moves in a particular direction, an entire national trajectory has been settled. That is not analysis. It is persuasion by compression.

When the logical steps are restored, the certainty dissolves. What remains is a contested picture, with strengths and constraints evolving in parallel. The article insists the case is closed. The evidence does not justify that confidence.

-

The Chinese Embassy Panic Is a Legal Failure

A legal analysis of how fear-driven narratives distort policy, law, and Britain’s China debate. -

The Surplus Delusion

Why trade surpluses are routinely misused as evidence of economic pathology. -

The British Press and the Uyghur Story It Wants You to Believe

An examination of how media narratives harden into assumed facts. -

How a Dutch Factory Became a Weapon in the Tech War With China

Industrial policy, law, and strategic pressure inside Europe. -

The Carbon Ledger

A data-driven look at emissions, responsibility, and selective environmental framing. -

Fujian: The Carrier That Ends America’s Monopoly at Sea

What naval capacity reveals about industrial depth and long-term power. -

When Britain Turns Trust Into a Weapon, It Cuts Its Own Throat

How institutional credibility is eroded by politicised enforcement. -

Europe’s Empty Promises

A study in how rhetoric replaces capacity in modern geopolitics.