Britain’s Economy Is Not Broken. It Is Being Quietly Mismanaged

Britain does not feel like a country in crisis. That is part of the problem.

Most weeks, the economy is described in calm language. Growth is subdued. Prospects are challenging but improving. There is always a sense that things are being managed, adjusted, stabilised. Nothing sounds broken. Yet wages barely move. Housing becomes unreachable. Energy costs feel arbitrary. Investment hesitates. The country works harder to stand still.

This is not an accident. And it is not bad luck. Britain’s problem is that it has quietly replaced economic judgement with administration. Instead of letting prices, profits, and losses tell us what works and what fails, we increasingly decide outcomes first and then manage reality to fit them.

The result is a system that looks stable while slowly losing the ability to tell the difference between creating wealth and consuming it.

Britain’s economy in early 2026, in brief:

Headline GDP growth forecasts cluster around 1.0–1.3 percent. Unemployment is expected to drift toward 5 percent. Inflation has cooled, largely through policy tightening rather than productivity gains. Public spending now sits close to half of national output, while private business investment remains below pre-2008 levels. Stability, such as it is, rests heavily on the expansion of the state rather than renewed private dynamism.

A simple test: how do we know what works

In a normal market, success and failure are obvious. If a café serves bad food at high prices, customers stop coming. The owner loses money. The café closes. Resources move elsewhere. Painful, but clear.

That clarity depends on prices being real and losses being allowed. Britain has spent years dulling that signal. We increasingly treat activity as success, regardless of whether it produces value. Spending counts as output. Employment counts as progress. Cost is confused with worth.

The state expands because it cannot go bankrupt. Its failures do not close. They are rolled forward, refinanced, or redefined as priorities. This creates a dangerous illusion: the country appears busy, fair, and managed, even as its productive core weakens.

One reason the illusion persists is statistical. Public sector output is recorded at cost, not at value revealed through exchange. When spending rises, measured output rises automatically. By contrast, private sector output is continuously tested by profit and loss. This asymmetry allows economic expansion to be reported even as underlying productivity flatlines.

When the public sector “drives growth”

Listen carefully to how growth is now described. You will often hear that it is supported, or driven, by public spending. That should set off alarm bells.

In the private economy, output is judged by what people voluntarily pay for. In the public economy, output is valued at cost. If more money is spent, more output is recorded, whether or not anyone would choose it freely.

Imagine a builder paid to dig a hole and fill it back in. He is busy. He is employed. Money changes hands. But nothing has been created. When large parts of the economy operate like this, growth figures lose meaning. The country can spend more and produce less, without the accounts showing the difference.

Failure becomes invisible.

Housing: when prices are forbidden to speak

Housing shows the problem most clearly. Britain is not short of land. It is not short of builders. It is not short of money. It is short of permission.

Instead of prices encouraging new supply, building is rationed through planning committees, political bargaining, and delay. Land does not respond to demand because it is not allowed to.

The result is predictable. Prices rise, but homes do not. Capital flows into land banking and legal navigation rather than construction. Young people are excluded not by markets, but by the suspension of markets.

This is often described as market failure. It is what happens when markets are not allowed to function.

Energy: hiding scarcity makes it worse

Energy policy follows the same logic. When prices rise, they are capped. When supply tightens, subsidies are added. Pain is softened immediately, but the signal is lost.

High prices are supposed to tell producers to invest and consumers to conserve. When that message is muffled, shortages persist and investment stalls. Private capital hesitates because returns depend not on demand, but on regulatory favour.

Every intervention creates a new distortion, which is then used to justify another intervention. Scarcity is moralised. Reality is managed. No ledger records the cost.

Cheap money and the comfort illusion

For years, money was made artificially cheap. Interest rates were treated as tools to maintain confidence rather than as prices reflecting real risk and time.

Asset prices inflated. Weak firms survived longer than they should have. Capital stayed trapped in low productivity uses because failure was postponed, not resolved.

Low productivity stopped being a crisis because its effects were masked. Cheap credit acted like painkillers for a broken limb. The patient feels better. The injury worsens.

Now, optimism is often built on the expectation that rates will fall again. As if the same medicine, given once more, will produce a different outcome. This is not stability. It is delay.

There is a hard rule in political economy: when intervention blocks correction, it must either be withdrawn or multiplied. Britain has chosen multiplication. Each distortion demands another fix. Each fix narrows the space for retreat.

Living off the past

Britain is not collapsing. It is coasting. It lives off accumulated capital: financial, institutional, cultural. The inheritance is large. That is why decline feels gentle.

But inheritance runs out. When it does, adjustment will not be optional. It will be forced by balance sheets rather than debated in committees.

The choice is simple. Restore the signals that tell a society what works and what fails. Or continue managing decline until reality insists on being heard. For the moment, Britain has chosen comfort over clarity. History suggests that choice has an expiry date.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

-

Britain’s Pressure Economy: Why 2026 Will Test Housing, Bills, and Social Order

A forensic look at how arrears, enforcement, and household stress turn economic strain into political instability. -

Britain’s Quiet Crackdown: How Insurance, Courts, and Banks Are Building the 2026 Order

How power shifts through contracts, court throughput, and payment rules, long before Parliament stages the argument. -

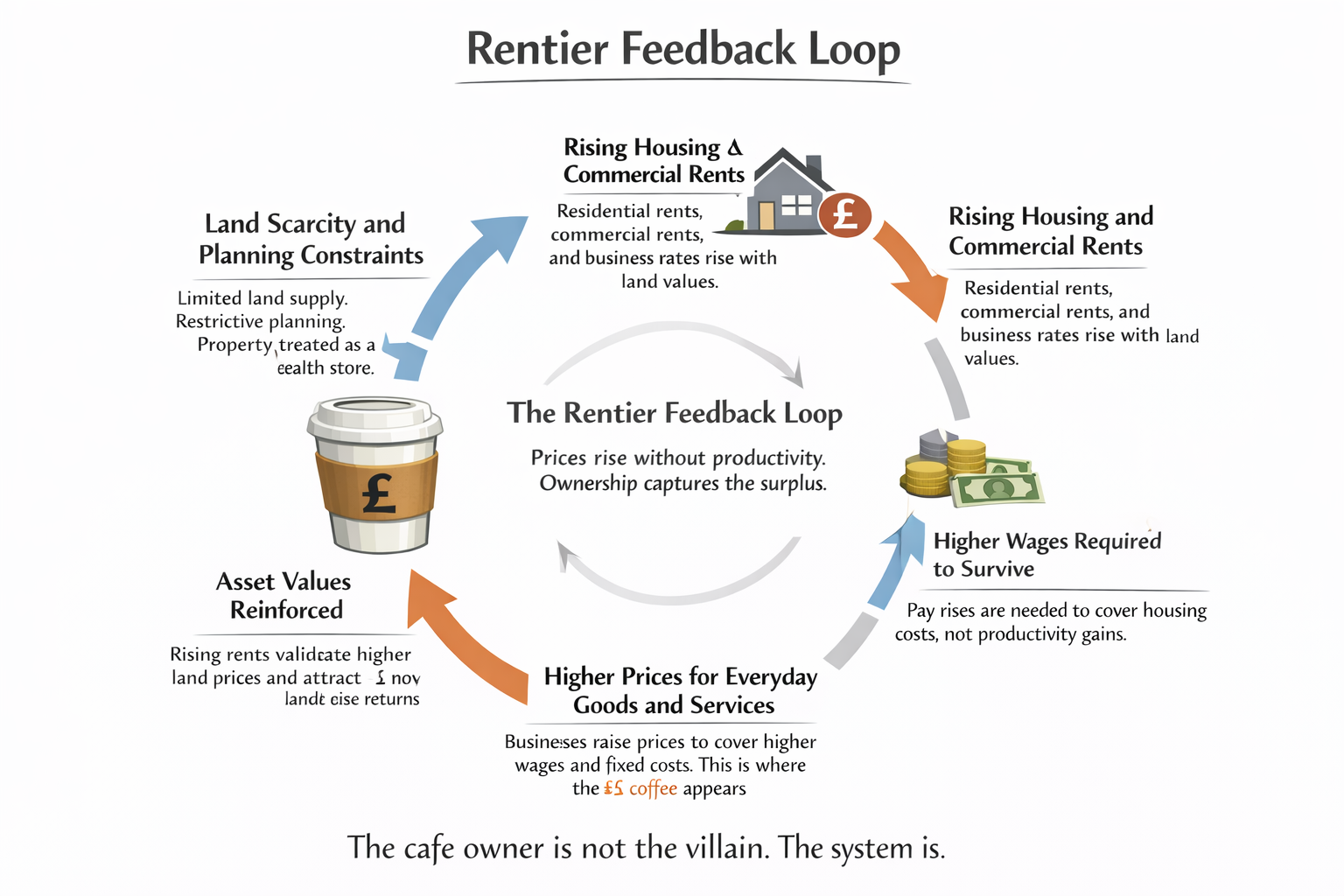

Britain’s Productivity Collapse and the Rentier Trap Martin Wolf Will Not Name

Why the productivity story is not a mystery, and how Britain became an extraction system disguised as an economy. -

When Britain Turns Trust into a Weapon, It Cuts Its Own Throat

A structural argument that Britain is spending down its last strategic asset: credibility in law, finance, and custody. -

London Is Becoming an Industrial Disassembly Market and 2026 Will Accelerate It

Why breakups, buybacks, and takeovers are turning Britain’s productive base into a liquidation process with paperwork. -

When “As Safe as the Bank of England” Stops Being True

What changes first when a services economy trades away neutrality, and markets begin repricing “safe” custody. -

Britain Is Spending the Interest on Russia’s Frozen Money. Some call it theft

How war finance turns custody profits into policy, and why the trust costs compound faster than ministers admit.