Why Jewish Humour Is Not Self-Deprecation

The lazy reading is that Jewish humour is self hatred dressed up as wit. The smarter reading is that it is self control dressed up as laughter.

Yes, Ashkenazi humour often turns inward. It will mock the anxious man, the over thinker, the pushy mother, the hapless schlemiel. But the target is not Jewishness. The target is certainty, vanity, and the fantasy of purity. The joke is a small act of discipline that prevents the mind from turning into a tribunal.

Freud noticed something basic that still matters: jokes told by Jews about Jews are not the same thing as jokes told by outsiders about Jews. The outsider joke tends to treat the Jew as a comic object. The insider joke keeps agency with the teller. It admits fault, but it also understands the connection between fault and strength, which is why it can land without surrendering dignity.

The mistaken frame: self depreciation

“Self depreciation” suggests abasement. It implies the speaker is lowering themselves to win approval from a hostile audience. Sometimes that happens in assimilation comedy. But it is not the engine of the tradition.

A better frame is preemption and inversion.

You name the accusation before your accuser can weaponise it. You exaggerate it to the point of absurdity. You steal its moral force. That is not submission. It is a controlled demolition of the charge.

Scholars who work on ethnic humour describe this pattern as defensive and subversive, a form that survives by flipping vulnerability into a tool.

What Jewish jokes protect against

The moral intoxication of certainty

Ashkenazi humour is a solvent. It dissolves grand statements, heroic self narration, and ideological purity. It treats absolute certainty as a symptom, not a virtue. That sceptical posture is one reason “Jewish humour” becomes visible in modernity, where ideologies and national projects demand total belief.

This is where irony becomes a survival skill. Irony lets you live inside a world of claims without being owned by them. It allows distance from slogans, including your own.

Utopias, including Jewish ones

There is a particular Ashkenazi suspicion of the perfect future. Not because hope is banned, but because redemption talk can slide into coercion. The joke keeps a wedge between hope and certainty.

That is why the schlemiel matters. He is not only pathetic. He is a theological and political warning: history does not obey blueprints; virtue does not guarantee victory; the person with a plan is often the person about to do harm. The humour protects against fanaticism by mocking the kind of personality that needs the world to be simple.

Tyranny, humiliation, and the psychology of powerlessness

In conditions of oppression, humour performs a reversal. It gives the powerless a small zone of sovereignty. Humour helps communities respond to oppression and keep identity intact, including through the overt reversal ritual of Purim.

This is not escapism. It is a refusal to let the oppressor control your inner life. The laugh is not joy. It is possession: you still own your mind.

Internal policing: keeping the group from turning cruel

Jewish humour does not only defend against enemies. It defends against the group’s own temptations. In tight communities, moralism can metastasise. So can judgement, status games, and public shaming.

A joke can puncture self righteousness without requiring a sermon. It can correct without humiliating. It can say, “watch yourself,” without triggering a war. This is part of why jokes in rabbinic culture often function as interpretive instruments rather than entertainment.

Why it reads like self mockery

Because it often uses the self as the vehicle. The humour will choose a familiar Jewish character type and push it to the edge, not to concede contempt, but to neutralise it.

That choice also has a strategic reason: if you aim the joke outward, you risk cruelty, and you risk feeding the hostile gaze. Aim it inward and you keep control of the moral terms. You set the boundaries of the caricature. You decide what is fair to ridicule and what is not.

Self directed comedy can become perilous when it starts mirroring external antisemitic frames rather than resisting them. The tradition is not naive about this. It knows when self mockery stops being a weapon and becomes an invitation.

A note of realism

There is also a scholarly challenge worth taking seriously: the very idea of a unique “Jewish humour” is partly a modern myth, built by intellectuals who wanted to explain a style that might be better understood as a product of specific social settings, languages, and migration patterns.

That critique does not kill the argument. It tightens it. It forces you to be specific: not “Jews are funny,” but “in Yiddish speaking Ashkenazi life, under certain pressures, particular comedic habits developed that perform particular defensive and anti fanatical functions.”

The core claim

Ashkenazi humour is not self depreciation. It is a method for staying human when the world, and sometimes your own community, is trying to turn you into an object or an instrument.

It protects against oppression by reclaiming inner sovereignty.

It protects against fanaticism by humiliating certainty.

It protects against utopia by refusing the clean ending.

And it protects against pride, including Jewish pride, by reminding you that any identity which cannot laugh at itself is an identity preparing to persecute someone else.

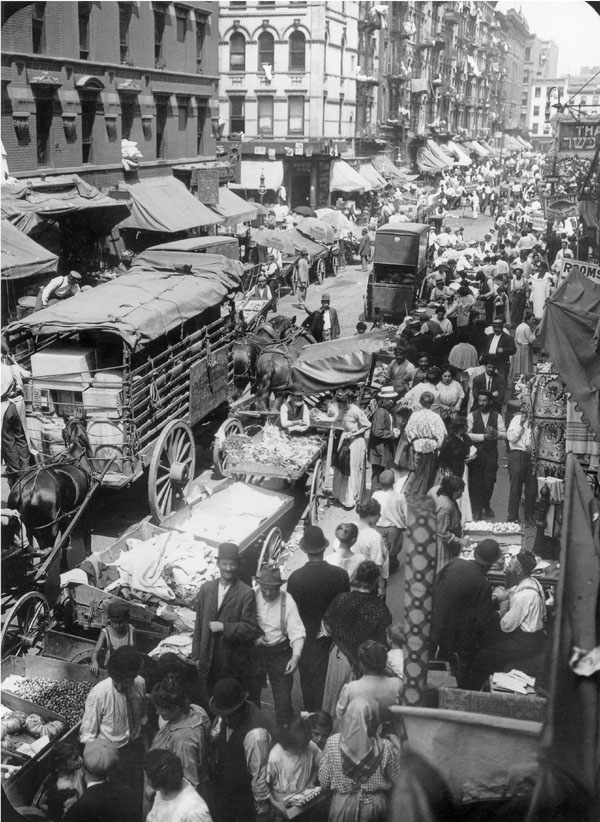

South Williamsburg: Where Yiddish Still Organises the Street

A first hand account of Ashkenazi street life in South Williamsburg, where language, ritual, and habit quietly order daily existence.

Ashkenazi Ethics and the Burden of Conscience

How a moral tradition shaped under pressure treats restraint, humility, and obligation as measures of strength rather than weakness.

Yiddish New York: A Living Heritage of Torah, Safety, and Continuity

How neighbourhood life, language, and institutions turn memory into continuity rather than nostalgia.

Tikkun Olam: The Jewish Call to Repair the World

An explanation of repair as practical responsibility, grounded in limits rather than abstract moral exhibition.

Yom Kippur Sermon: Peace Amid Ashes

A hard argument for moral discipline under fear, where memory restrains hatred rather than inflaming it.