Elections Without Consent

Markets soar, jobs shrink, and faith in the system collapses beneath the curve

Democratic wins read as momentum on the surface. The deeper signal is institutional mistrust and a widening break between market outcomes and lived reality.

Democrats posted wins in Virginia, New Jersey, and parts of New York, and they secured a California ballot change that could produce several additional House seats in 2026. The optics suggest recovery. The substance suggests exhaustion. These were reprimands, not endorsements.

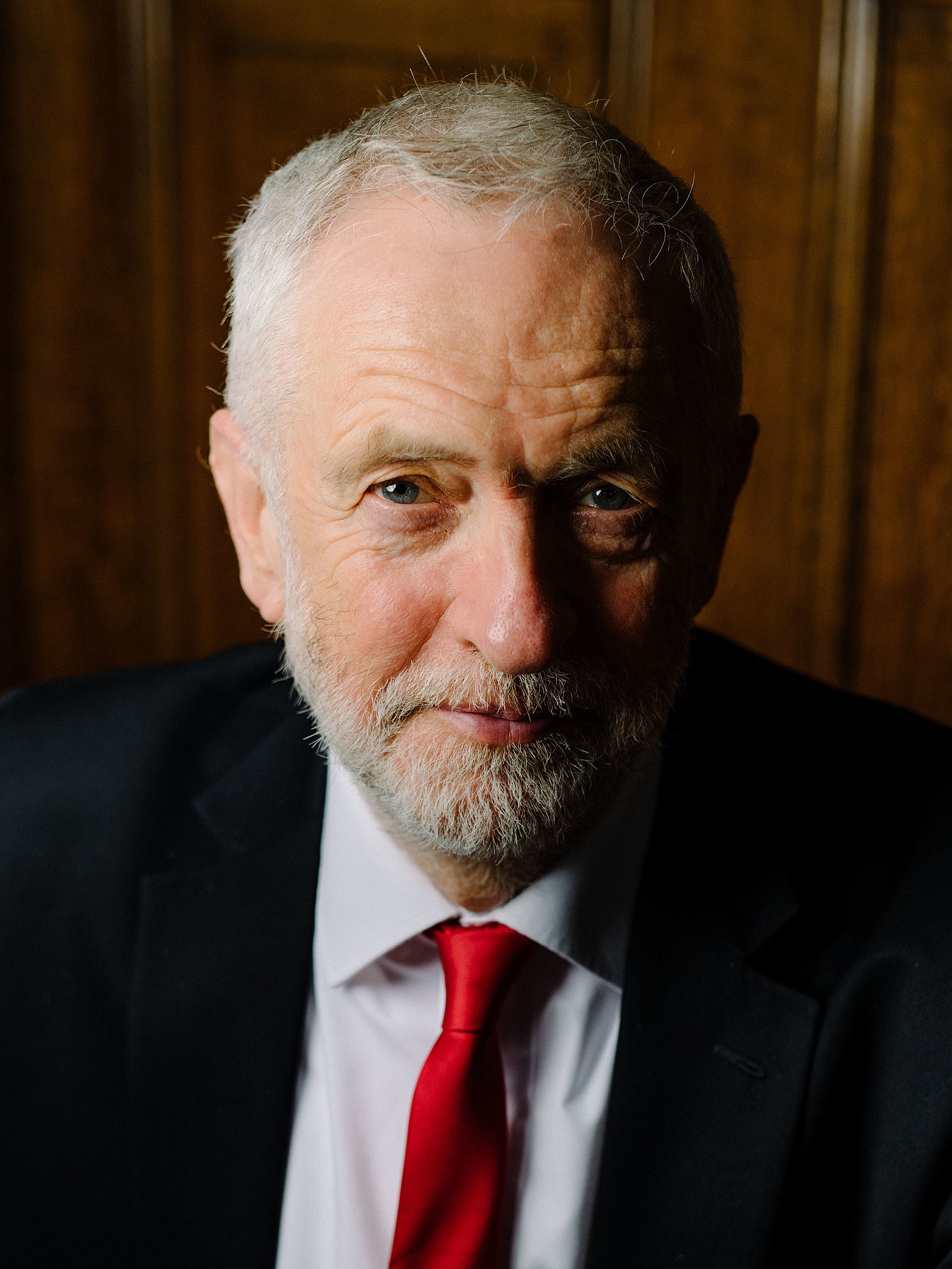

The pattern mirrors Britain before its last general election. Electors punished a tired order while finding little to admire in the alternatives. The same mood now defines the United States. A party can gather victories and still lose legitimacy.

The fracture is structural rather than ideological. One economy floats on asset prices, leverage, and technology speculation. The other exists in rents, medical bills, and wages that lag. Markets levitate. Households calculate.

Analysts circulate a chart that places equity indices on an upward run while job openings slide. The picture has become a shorthand for an economy that rewards capital and starves labour. Whether one causes the other is disputed. The divergence is not.

When politics fails to reconcile the two economies, elections become instruments of reprisal rather than selection. Voters cast judgment on pain rather than program. That is how institutions burn credibility without noticing the smoke.

Corporate America is preparing roughly four hundred billion dollars in artificial intelligence infrastructure over the next year. The deployment is pitched as a productivity revolution. Early returns are thin. An MIT linked survey reported that most firms adopting generative tools saw no measurable financial gain. The labour market reads the signal in simpler terms. If the money is real, someone will be removed from the payroll.

If the optimism is wrong, the correction will strike markets. If the optimism is right, the displacement will strike workers. Either path produces instability. The only open question is where the shock lands first.

A widening belief has taken hold that foreign and economic policy now reflect the preferences of a billionaire donor class more than the preferences of voters. This is perception rather than proven fact. The political effect is not in dispute. Commentators cite the concentration of campaign finance, the revolving door between finance and policy, and the role of advisory boards that sit close to executive power.

Conservative and nationalist voices have amplified this theme, framing strategy abroad as a market traded by access rather than debated by citizens. The result is a legitimacy gap that grows with every budget cycle and every funding bill that appears detached from public priorities.

Voter unease over the current foreign crisis now overlaps with the donor narrative. Support for the official line has weakened among independents and younger voters. Isolationist impulses rise. The governing class offers continuity. The electorate registers fatigue.

A constitutional fight over tariff authority could narrow presidential discretion in trade and in revenue policy. New limits would remove a useful lever, they would expose fiscal gaps that asset prices have concealed, and they would leave the administration more dependent on market calm than prudence would suggest.

The remap in California may change the House arithmetic. It will not repair legitimacy. Democrats risk losing the voters who delivered these gains. Republicans risk a break between donor aligned operatives and a base that reads corporate globalism as betrayal. The country now rests on a tripod of instability, artificial intelligence speculation, the split economy, and the perceived capture of policy by wealth. Geometry like that does not hold for long.

Numbers can rise while belief falls. That is the stage we have reached. The midterms will not decide which party governs in the usual sense. They will decide whether governing still commands consent.