The Rent Crisis Was Manufactured — To Serve Profit, Not Shelter

By Esther Cohen

Homes were reclassified as assets. Scarcity was cultivated. Empty houses multiplied while permissions went unbuilt. Private equity moved in. The housing system no longer delivers stability but extraction, driving poverty and deepening inequality

In 1977, Parliament passed the Rent Act. It delivered three essential protections. Tenants gained security of tenure: eviction was possible only on statutory grounds. Rents were fixed independently by officers instructed to exclude scarcity from their calculations. Families had succession rights, ensuring continuity after a tenant’s death. For a time, housing was treated as shelter, not a commodity. The system stabilised the private rented sector. Rents were predictable. Tenancies were durable. Families could plan their lives without constant fear of displacement.

That system did not collapse. It was dismantled. The Housing Act 1980 introduced insecure contracts. The Housing Act 1988 abolished new protected tenancies, authorised market rents, and made the assured shorthold tenancy the default. By January 1989, the protections of the Rent Act were extinguished. Security gave way to precarity. The six-month tenancy became the norm. Fair rents gave way to market rents, dictated by scarcity and speculation. Homes were reclassified as assets, to be traded and leveraged for profit.

The consequences were stark. Families moved repeatedly under threat of eviction. Incomes were swallowed by rent. Landlords acquired not only an asset class but a guaranteed stream of returns. The imbalance of vulnerability was total. For tenants, the loss of income could mean immediate destitution. For landlords, arrears or voids were an inconvenience. Even small landlords who complained of “bad tenants” retained the advantage of ownership. One side held a secure asset. The other had no fallback.

Illustrative cases make the point. A family renting under the old system once spent around a quarter of income on housing. After deregulation, their rent doubled within three years. They were forced to move twice in six, each time under pressure from the landlord, before leaving the private sector altogether. At the other end, a landlord letting out a modest semi described a tenant who fell into arrears after job loss. The property declined, repairs mounted, and the tenancy collapsed. For the landlord, the outcome was lost rent and redecoration costs. For the tenant, it was the loss of both home and livelihood. The asymmetry is clear.

Abuse has persisted under both regimes. Even during rent control, unlawful tenancy agreements circulated. In one case, residents of a listed building endured decades of breaches before resolution. The weakness has not been regulation in principle but its enforcement. Local authorities, under-resourced and often reluctant, failed to police the law. Regulation without enforcement is a paper shield.

Scarcity remains the industry’s permanent defence. The evidence shows it is manufactured. Nearly one million homes lie empty across the UK, including more than 260,000 long-term vacancies. Many stand in city centres, abandoned or converted into luxury units at unaffordable rents. At the same time, more than 1.1 million homes have planning permission but remain unbuilt. Developers hoard land and approvals because scarcity sustains values. This is not a neutral outcome of supply and demand. It is a strategy.

The cost burden illustrates the crisis. Across England, renters spend on average 36% of gross household income on rent, according to official figures. In London, the figure rises above 40%, with extremes such as Kensington and Chelsea where three-quarters of income disappears into rent. In Bristol and Bath, tenants part with around 45%. Even in Wales and Northern Ireland the average is about a quarter of income — still above historical thresholds of affordability. Among the lowest-income households, the figure reaches 63%. One in five renters now spends more than half of take-home pay on housing.

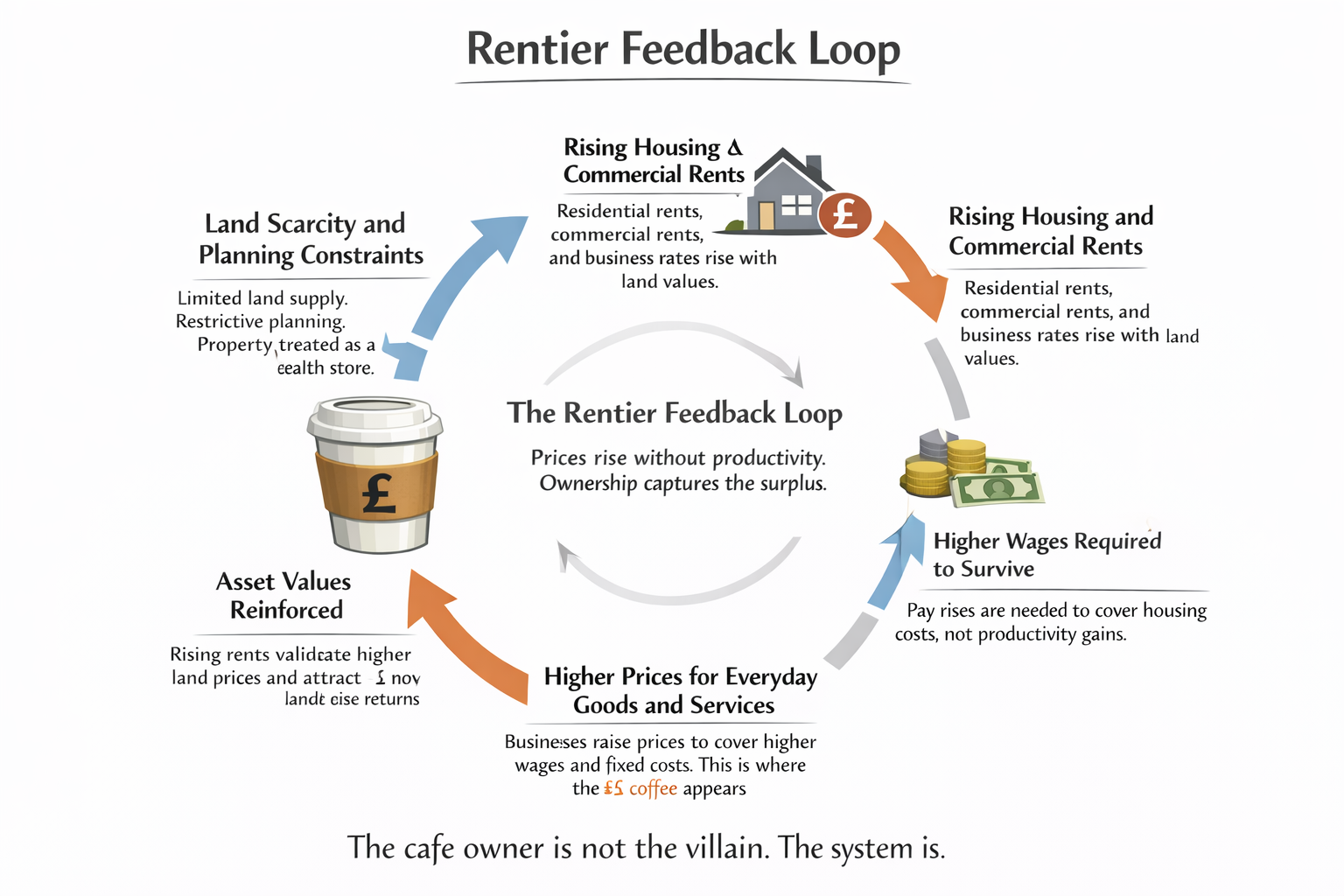

This is a direct driver of poverty. Wages that should fund food, education, transport and savings are siphoned into rent. Living standards collapse. Inequality deepens. Society fractures into two groups: those extracting rent and those paying it. No society can sustain a system where such a disproportionate share of labour’s earnings is consumed by housing costs. It is a short-term model of exploitation that undermines long-term stability.

The same pattern extends beyond housing. Care homes charge astronomical weekly fees. Veterinary practices are consolidated by corporate groups. GP surgeries and dental services are increasingly financialised. Energy and water bills are among the highest in Europe. Funds such as BlackRock consolidate housing portfolios. Essential services are redefined as guaranteed income streams. Citizens become revenue sources. What should be public goods are treated as financial instruments.

The political response has been inadequate. Council housing stock continues to collapse: in 2024–25, eight times more homes were sold under Right to Buy than built. Developers continue to bank land. Of 2.7 million homes granted planning permission in the past decade, only 1.6 million have been delivered. The new government has threatened fines and land seizures. Until enforcement occurs, imbalance will persist.

The lesson is not ambiguous. The Rent Act did not fail. It succeeded. It provided affordability, security and stability. That is why it was dismantled. Regulation worked for tenants but constrained landlord profit. Deregulation reversed the balance. With regulation, tenants are housed. Without it, they are exploited.

The solutions are known. Security of tenure must be restored. Independent rent setting must return, with scarcity excluded from calculation. Local authorities must be resourced to enforce the law. Empty homes must be brought back into use, particularly for social housing. Planning permissions must be subject to “use it or lose it” penalties. Public housing stock must be expanded, with councils empowered to build and buy back. Essential services must be de-financialised, removed from speculative markets.

Britain’s housing crisis is not natural. It is legislated. In 1989, Parliament ended fair rents and security of tenure. Right to Buy hollowed out social housing. Empty homes multiplied. Planning permissions piled up while developers withheld delivery. Private equity colonised housing. Rents now consume between one-third and two-thirds of wages, driving poverty and inequality.

This is not a neutral market outcome. It is a policy choice. Unless reversed, it will intensify inequality and destabilise society. The evidence is conclusive. Without regulation, tenants are bled. With regulation, they are housed.

1 Response

[…] The Rent Crisis Was Manufactured — To Serve Profit, Not Shelter Tracks the decline of rent regulation in Britain and argues that deregulation has created precarity for tenants and profit for landlords. […]