The Tiger That Wasn’t There: A Story of Media and the Ghosts of Empire

In recent weeks, several British and international media outlets, published headlines claiming that “starving North Koreans are hunting tigers for food.” Each attributed the story to a new academic study, presenting it as fresh evidence of famine-driven desperation inside the DPRK. The impression given was of a population so reduced by hunger that it had turned on one of the world’s rarest predators. Yet a closer examination of the source material, the study’s methodology, and the biological record reveals that this claim is unsupported by credible evidence and rests on the same narrative reflexes that have long shaped Western reporting on the non-West, a blend of moral theatre, selective sourcing, and unexamined assumptions about civilisation and savagery.

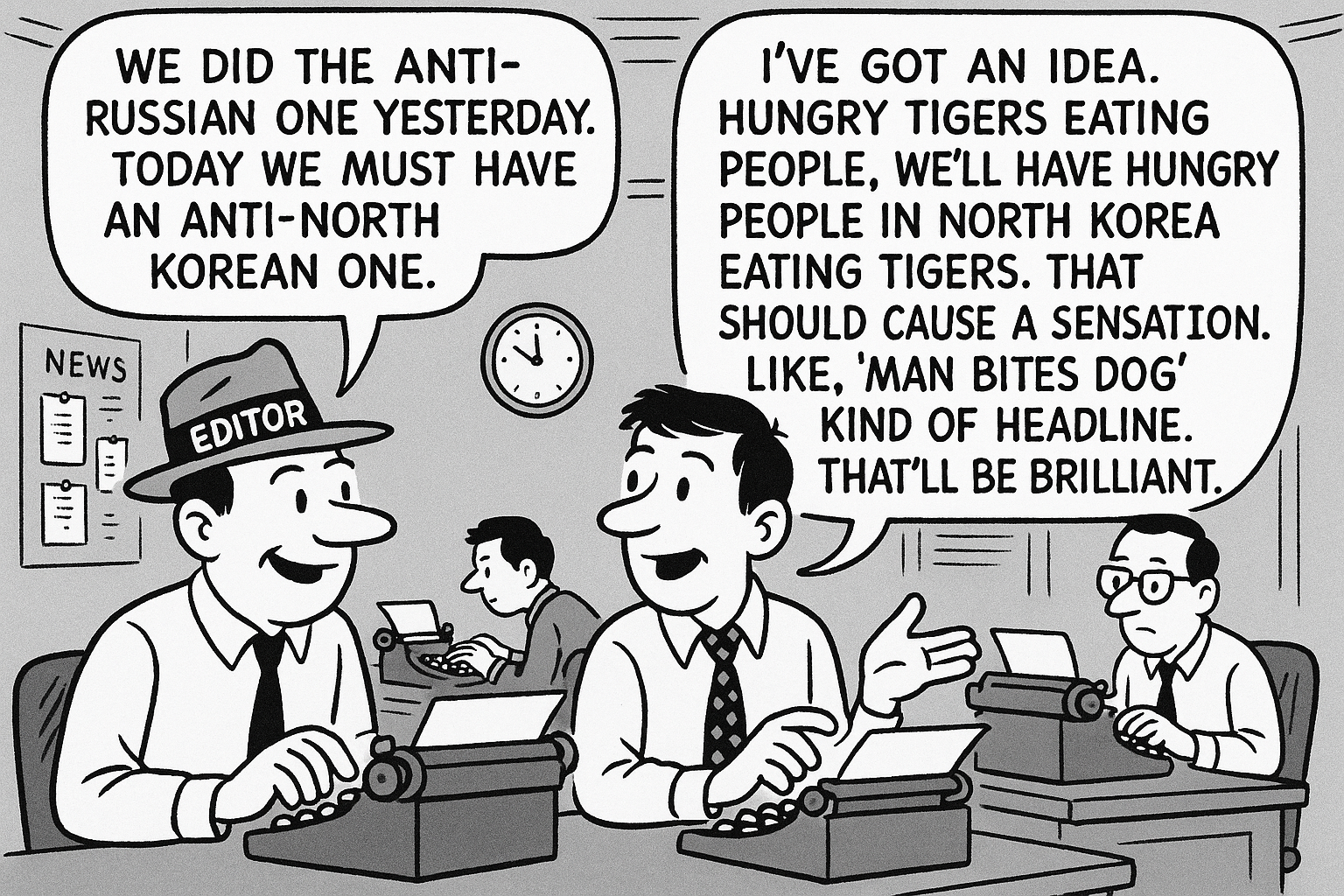

For generations, the national press in Britain enjoyed a monopoly on framing global narratives. That era is over, but the habits persist. The “tiger story” is a case study in how those habits, when combined with the modern pressures of the news cycle, can manufacture a reality that is more allegory than fact.

Deconstructing the Narrative

A close reading of the source material reveals a chasm between the academic paper and the news report. The study, as the original article failed to emphasize, was based solely on interviews with 42 defectors, many of whom left North Korea during the famine of the 1990s. The authors themselves included clear caveats, noting that verification was “challenging” and conclusions “should be drawn carefully.”

The most damning evidence, however, is biological. According to the World Wildlife Fund and the Wildlife Conservation Society, there are no confirmed resident populations of wild Siberian (Amur) tigers in North Korea, though a few animals may occasionally cross the border from China. Their range is confined mainly to the Russian Far East and Northeast China. With no confirmed resident tiger population, claims of systematic tiger hunting in North Korea lack evidential support; occasional dispersers are at most a theoretical risk.

There is no verified evidence of wild tigers being hunted in North Korea today. While Chinese authorities have reported seizing DPRK labelled “tiger bone wine,” these products are typically not DNA verified, and their contents and origins remain uncertain.

There is no contemporary field data from inside the country, no genetic sampling, and only uncorroborated trade reports, certainly nothing to support a claim of a present day trade in tiger parts from North Korea.

The Long Shadow and the Short Reign

To understand why such a story resonates, one must confront the uncomfortable weight of history. It is a common but profound error to mistake a recent balance of power for a permanent civilizational hierarchy. Korean civilization, with its dynastic courts, bronze metallurgy, and astronomical charts, predates the English state by millennia. The Silla dynasty unified the peninsula and raised Buddhist temples that still stand while Britain was a patchwork of warring tribes. The Goryeo kingdom minted coins and codified laws; the Joseon dynasty created the scientific marvel of the Hangul alphabet.

The publication transformed a tentative, historically situated academic hypothesis into a present tense horror story. This was less journalism than narrative alchemy.

The so called “Age of Empire,” during which Britain dominated through industrialized violence and mechanical advantage, was a brief, two century interlude in this long human story. It was an age of extraction, not inherent wisdom. As the historian Adam Tooze notes, before colonization, India and China accounted for a massive share of global GDP, a fact of scale and continuity, not destiny. The Industrial Revolution disrupted this balance temporarily; its erosion is not so much a “decline” of the West as a rebalancing, what some economists call “the great convergence.”

The Psychology of a Fading Frame

The tiger story, then, is not really about North Korea. It is about a deep seated psychological need to project one’s own anxieties onto a foreign “other.” The fear is not that Koreans are eating tigers; it is that the moral order that justified empire has reversed. The nation that once preached fiscal discipline to the world now grapples with its own debt. The country that built railways across continents now struggles to maintain its own. The narrative of a “hungry world” serves as a consolation, a way to mask a more uncomfortable domestic reality.

When a major newspaper prints such a thinly sourced report, it risks turning analysis into allegory. It is engaging in a form of narrative therapy for a class struggling to accept a diminished global role. These stories of savagery abroad distract from the quiet crises at home: a shrinking economy, crumbling infrastructure, and the slow dawning realization that “punching above our weight” is an increasingly unsustainable national fantasy.

The Imperative of Vigilance

The final irony is that the empire which so often branded others as barbaric now finds itself culturally adrift, its authority undermined by its own inability to tell the truth about itself and the world. Civilizations endure through self renewal and honest self appraisal; empires fade when they can no longer distinguish myth from reality.

There is a lesson in the absurdity of the tiger that wasn’t there. The tigers were never hunted in the hills of North Korea, but the truth is constantly being hunted, and often cornered, by unverified narratives. The real task of a free press in a mature society is not to console with fables, but to challenge with facts. It is to teach citizens to question, to verify, and to demand evidence before belief. In the end, we must learn to hunt the narratives before the narratives hunt us.

And yet there is a lesson in its absurdity. The tigers were never hunted, but the truth still can be if citizens learn to question, verify, and demand evidence before belief. That is the real task of a free society: to hunt narratives before they hunt us.

The newspaper report claimed that North Koreans were eating tigers to survive. It cited a scientific study as proof that famine and desperation led people to hunt endangered wildlife, including the Siberian tiger and the Amur leopard.

The claim collapses under examination.

- The study method: based solely on interviews with 42 defectors, many of whom left North Korea years or decades ago. No fieldwork or independent verification was carried out inside the country.

- What the authors wrote: they warned that verification was “challenging” and that conclusions “should be drawn carefully.” They also conceded there is little evidence regarding tiger populations in North Korea.

- The biological fact: there are no confirmed resident tigers in North Korea; dispersing animals from China may occasionally cross the border but none are verified as hunted.

- The historical context: most testimony refers to the 1990s famine, when some people hunted smaller wild animals for food. There is no verified evidence of tiger hunting today, though the study notes ongoing illegal exploitation of other wildlife species.

- The trade evidence: as a non Party to CITES, North Korea files no trade data; Chinese customs have seized DPRK labelled “tiger bone wine,” but contents and provenance remain unverified.

- The conclusion: a tentative, heavily qualified academic paper was turned into a present tense horror story. This is narrative theatre built on a misreading of the data, not verified reporting.

- Public trust: surveys indicate that around 35 to 40 percent of people say they trust mainstream outlets to tell the truth. Each exaggerated story further erodes that remaining confidence.

- Bottom line: the assertion that “North Koreans are eating tigers” is biologically implausible, methodologically unsound, and chronologically false. It reveals less about North Korea and more about the persistence of editorial habits that keep old myths alive.