Chagos and the British Colonial Myths That Refuse to Die

I read this article this morning at breakfast. It was about the Chagos Islands. As I read it, it became clear that I was not really reading about Chagos at all. I was reading a familiar reflex of the British press: a way of talking about empire that still flatters us, reassures us, and quietly shields us from the harder truths of our own history.

The piece is written to feel bracing and unsentimental. In reality, it is sentimental about Britain and cynical about everyone else. It opens with a caricature, the anti colonialist wokester, so that the reader is trained, before any evidence is considered, to treat moral and legal constraint as fashion, and to treat any challenge to British sovereignty as a kind of social pathology. This is not argument. It is narrative pre emption.

What follows is presented as realism. In fact, it rests on a series of misconceptions that have survived precisely because they are comfortable for a particular English class: that empire was largely administrative, occasionally regrettable, and ultimately benevolent; that its harms were incidental rather than structural; and that any modern attempt to constrain British power must therefore be driven by guilt rather than by law, history, or material reality.

The article concedes one wrong, the removal of the Chagossians to make way for the Diego Garcia base, and then treats that wrong as a closed chapter. From that point onward, British sovereignty is assumed to be the natural baseline. Any challenge to it is framed as emotional indulgence, foreign manipulation, or fashionable self loathing.

This is a very old English habit. Admit one sin briefly, then demand absolution.

But Chagos is not a mood story. It is a late, unusually clean example of a familiar imperial method. A territory is detached during decolonisation, relabelled, and then emptied of people so that strategic and economic priorities can proceed without political complication. That is not conjecture. It is exactly what happened between the mid nineteen sixties and early nineteen seventies, when the entire Chagossian population was removed.

The British press article attempts to reverse the moral direction by arguing that the deal cannot be anti colonialist because many Chagossians say they wish to remain British, and because Mauritius is cast as the true imperial power. This sounds persuasive only if one ignores how colonial systems actually operate.

Colonial power does not rely solely on force. It reshapes the field of possible choices. When a population has been displaced, fragmented, and rendered dependent on the legal and economic categories of the power that displaced it, expressions of loyalty cannot be treated as proof of legitimacy. They often reflect constrained options, not free preference.

This is where the British press repeatedly confuses sentiment with structure. Empire is imagined as a relationship of affection rather than a system of extraction, coercion, and market design.

If readers genuinely want to understand why disputes such as Chagos still cut so deeply, they need to step outside the narrow frame of sovereignty and sentiment and look at the material record. What follows is not polemic. It is not a rant. It is the economic history that underpins modern anti colonial arguments and that is almost entirely absent from the British press discussion. These points are set out separately, not to interrupt the argument, but to educate those who were never taught how colonial systems actually worked.

The economic harm of colonialism: what was denied

Colonialism’s most enduring damage was not rhetorical. It was economic, institutional, and cumulative.

Education denied. After nearly two centuries of British rule, India entered independence with mass illiteracy still the norm. Literacy rose only from around three percent in the late nineteenth century to roughly sixteen percent by nineteen forty one. By contrast, Japan, never colonised, achieved near universal primary education by the early twentieth century. This was not cultural fate. It was policy choice. Education is the foundation of industrial labour, technical skill, and political agency.

Industrialisation blocked. India had long been a major textile producer. Under colonial trade arrangements, it was progressively repositioned as a market for manufactured imports and a supplier of raw materials. The loss was not only employment but learning. Industrialisation requires protected time to fail, adapt, and improve. Without tariff autonomy and infant industry protection, that process was throttled.

Markets designed for extraction. Colonial economies were structured to serve metropolitan needs. Credit systems, transport infrastructure, and trade circuits prioritised export and revenue extraction rather than domestic market formation. Capital deepening, industrial clustering, and technological spillovers were delayed by decades.

The compounding loss. The greatest harm was time. Japan industrialised while India waited. No amount of post independence effort can recover missing compounding.

Empire did not merely take wealth. It prevented wealth from being created.

Once this economic record is understood, the narrowness of the article becomes obvious. What is presented as realism is in fact an argument conducted with the most important facts removed.

At this point, a comparison becomes unavoidable. Not as a moral gesture, but as a control case. If colonialism is defended as benign or incidental, the only honest test is to compare societies that faced Western pressure but retained control over their development choices with those that did not.

Why Japan matters in this argument

Japan matters because it shows what happens when a non Western society confronts Western power without losing sovereignty over development policy.

Japan retained control over education, banking, tariffs, and industrial strategy. It built mass schooling early, mobilised domestic savings through national institutions, protected infant industries, and invested deliberately in infrastructure.

As a result, Japan industrialised within decades.

India entered the twentieth century with mass illiteracy, limited industrial depth, tariff policy shaped by imperial interests, and an economy structured around raw material export. The difference was not civilisational. It was institutional.

Japan demonstrates the core point broadsheet commentary avoids: development is the result of deliberate policy exercised under sovereignty. Colonial rule removed that choice.

This comparison matters because it strips away cultural alibis. It shows that what empire removed was not dignity alone, but policy space.

The article then widens out, folding Chagos into grievances about Europe, immigration, reparations, and decline. This is revealing. The issue is no longer the islands. It is resentment. Britain, we are told, is weakening itself out of guilt.

This is not history speaking. It is anxiety.

That anxiety depends on a further act of forgetting: what happened when colonial administration and economic control met resistance. The historical record here is not anecdotal. It is documented, quantified, and uncomfortable. It is set out separately below not for effect, but because it explains how economic systems were enforced when consent failed.

Killing and atrocities under colonial rule: how the system was enforced

India. The Bengal famine of nineteen forty three killed around three million people in a province that still had food. Earlier, at Amritsar in nineteen nineteen, British troops fired into an unarmed crowd, killing hundreds.

Africa. In Kenya during the nineteen fifties, tens of thousands were detained, tortured, or confined in camps and enclosed villages during the Mau Mau emergency. In the Congo, forced labour in the rubber economy contributed to the deaths of millions.

After independence, the elected Congolese prime minister Patrice Lumumba was assassinated with the involvement of external powers, becoming a symbol of how violently imperial interests reacted when genuine sovereignty threatened extraction.

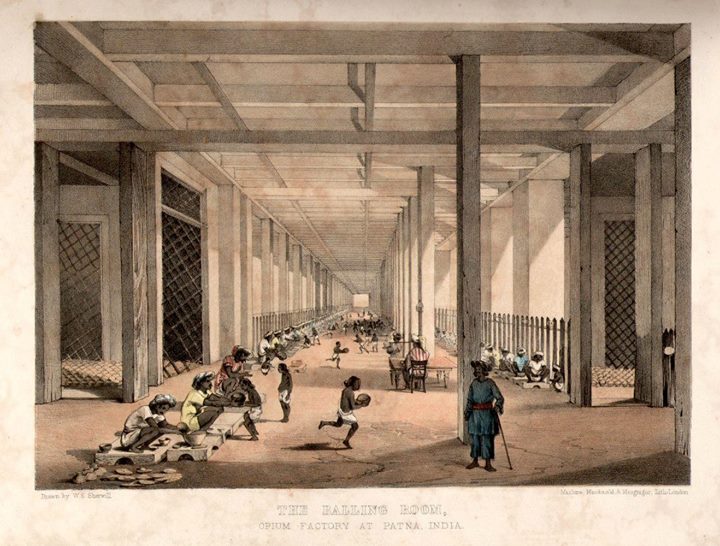

Forced removals. From Malaya to Kenya to Chagos, populations were relocated in the name of security and order. Removal was not an accident of empire. It was one of its tools.

Once this enforcement record is acknowledged, the moral certainty of the article collapses. Empire was not maintained by good intentions and shared values. It was maintained by law, markets, and, when necessary, organised violence.

The article is strongest where it worries that Chagossians may once again be excluded from decisions about their future. That concern is legitimate. Decolonisation conducted over the heads of the displaced risks repeating the original injustice.

But that concern is fatally weakened when it is used to defend British possession rather than to demand genuine repair. The displaced are invoked only when their voices align with British interests. When they complicate the story, they disappear again.

Chagos is not a morality play about woke lawyers and retired admirals. It is a late chapter in a long history of how power rearranges land, people, and markets, then calls the result common sense.

If Britain is diminished here, it is not by acknowledging that history. It is by the continued insistence, in parts of the British press, on treating empire as something that can be defended without cost, and remembered without consequence.

That illusion has survived longer than it should have. Chagos is uncomfortable precisely because it punctures it.

Further reading for context, not agreement

- Romila Thapar – The Past Before Us

- Shashi Tharoor – Inglorious Empire

- Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik – A Theory of Imperialism

- Amartya Sen – Poverty and Famines

- Priyamvada Gopal – Insurgent Empire

- Walter Rodney – How Europe Underdeveloped Africa

- Caroline Elkins – Britain’s Gulag

- Adam Hochschild – King Leopold’s Ghost

- Rashid Khalidi – The Iron Cage

These works are cited not as ideology, but as documentation. Readers may disagree with conclusions, but not with the scale of the historical record.

You might also like to read on Telegraph.com

- When ‘As Safe as the Bank of England’ Stops Being True

- Euroclear and Russia’s Frozen Assets Case

- The Frozen Assets Dilemma: Why the City of London Is Warning

- Europe Turns Frozen Russian Assets Into Permanent Leverage and Triggers a Global Legal War

- Can Europe Legally Use Russian Reserves to Fund Ukraine

- Gold, Sanctions and Power: How the Dollar Order Is Coming Apart

- When Britain Turns Trust into a Weapon

- Britain’s Abramovich Problem Is Not About Ukraine. It Is About Property

- Property Rights, Sanctions and the Abramovich Test for Britain

- Britain’s Productivity Collapse and the Rentier Trap