Britain’s Fractured Left: How Corbyn and Sultana’s New Party Threatens Labour’s Hold

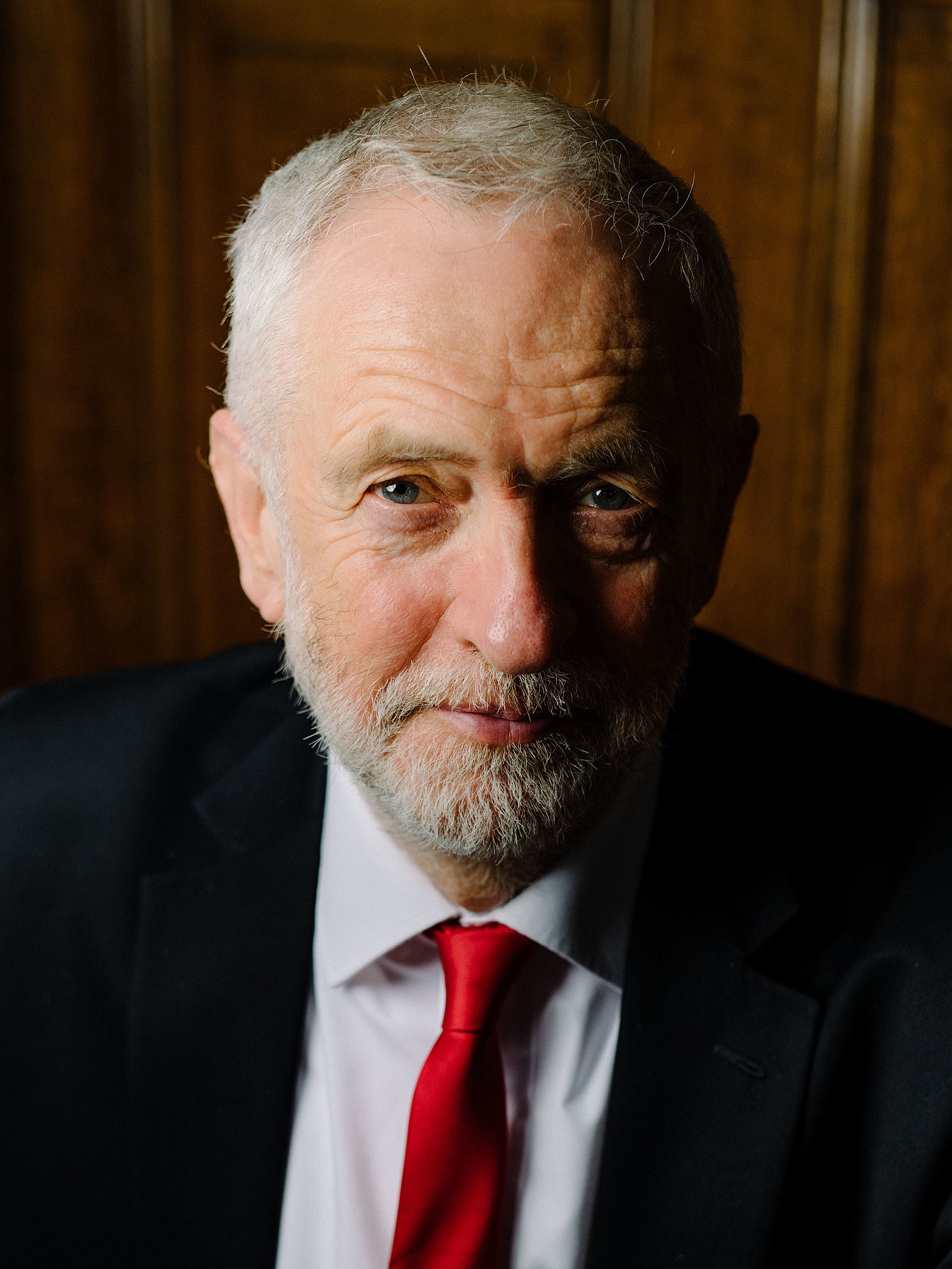

The start of this new political realignment comes as Britain drifts headlong into an economic crisis. The divide between rich and poor is widening, with wealth concentrating at the very top. For the working and middle classes, the system now feels rigged against them — a daily story of faltering infrastructure, declining public services, and a nation moving backwards. That sense of hopelessness has become the breeding ground for insurgent movements, from Nigel Farage’s resurgent right-wing populism to the new left-wing party spearheaded by Zarah Sultana and Jeremy Corbyn.

Britain’s Economic Backdrop: A Stalled Middle and Hollowed Local Services

Strip away the daily political noise and a blunt picture emerges. Real household incomes for the poorer half are projected to be lower by the end of the decade than before the pandemic; very-low-income households could be roughly 8 percent worse off by 2029–30 compared with 2019–20 unless urgent policy change occurs, according to the Resolution Foundation’s Living Standards Outlook.

Productivity — the engine of sustainable pay growth — has been chronically weak for more than a decade. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research finds that GDP per hour worked has grown by just 0.6 percent per year, an anemic pace that explains persistently flat real wages and underinvestment.

Meanwhile, economists such as Adam Tooze describe a phenomenon of “deconvergence” — Britain falling behind its peers — where wage and productivity growth stall in parallel, disconnecting headline GDP from everyday pay packets.

The state pension’s “triple lock” — an annual adjustment by inflation, wage growth, or 2.5 percent, whichever is highest — has become a costly burden on public finances. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates it has raised pension spending by around £11 billion a year. Long-term, it could cost billions more and heighten uncertainty for financial planning.

On the local front, councils are teetering on the financial edge. The Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Local Government Financial Review warn that up to half of councils could face effective “insolvency” without sweeping funding reform. With English councils projected to run a collective £9.3 billion deficit by 2026–27, many expect urgent government intervention to prevent service collapse.

The burden of debt interest further compounds the crisis. One report reveals councils now spend nearly 20 percent of council-tax income on interest payments alone, with rising pension contributions pushing total non-service expenditure toward 40 percent.

In short: growth alone won’t cut it. Pension obligations, local council distress, and low-income stagnation are coalescing into a suffocating economic snapshot. For many voters, Labour no longer seems capable of reversing the slide.

Labour Declared “Dead”

When Ms. Sultana, the young MP for Coventry South, declared flatly that “Labour is dead,” she launched not just a political critique but a verdict. Her declaration — at the launch of what is provisionally calling itself Your Party — highlighted a disaffection that has grown beneath the surface of British politics for years. Within weeks, nearly 800,000 had registered their interest online — a mass mobilization signalling that many do not believe Labour will dismantle the economic order they see as rigged.

From Blair to Starmer: Labour’s Long Drift from Its Base

The roots of this identity crisis span decades. Tony Blair’s “New Labour” pivot to the centre, market-friendly policies, and the technocratic “Third Way” reshaped the party’s DNA — alienating many working-class communities. Labour MPs from such backgrounds dwindled from over 70 percent mid-century to barely 8 percent by the 2010s. Keir Starmer’s continuation of cautious centrism — emphasising fiscal prudence — only deepened disillusion. Labour now reads to critics as a professional-class party that speaks softly to the financial expectations of Whitehall.

Discontent and New Alignments

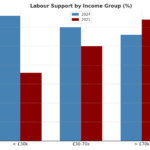

The result is a political vacuum. A growing bloc of voters, particularly younger and disenfranchised Labour members, express openness to alternatives. Polling suggests that nearly one in five voters would consider backing the new Sultana–Corbyn movement, while over 25 percent of Labour members are open to defection. This jeopardises dozens of marginal constituencies under first-past-the-post rules.

Labour insiders have responded — forming “Mainstream,” a counter-network attempting to reclaim ideological ground. Meanwhile, the Greens and the Scottish National Party continue to siphon urban and regional support, offering political homes for those feeling unrepresented.

Risks of Fragmentation

Critics warn that the new left formation could splinter the vote, inadvertently aiding the Conservatives or Nigel Farage’s Reform UK. Yet adherents argue that many disillusioned voters have already psychologically exited Labour. A coherent alternative might draw abstainers back and force a new, redistributive policy agenda to the fore.

Conclusion

For all the risks of division, the new movement may yet consolidate the left. Early signals suggest that Sultana and Corbyn’s fledgling organization could align with George Galloway’s Workers Party, which has traction in post-industrial seats, as well as the Green Party, and the Scottish National Party (SNP). Together they could attempt to rebuild the coalition Labour once embodied. But their adversary is equally clear. In the next general election, they will face the resurgent right, personified by Nigel Farage and his populist insurgency. This contest may very well redefine Britain’s political future as starkly as the Blair era once did.