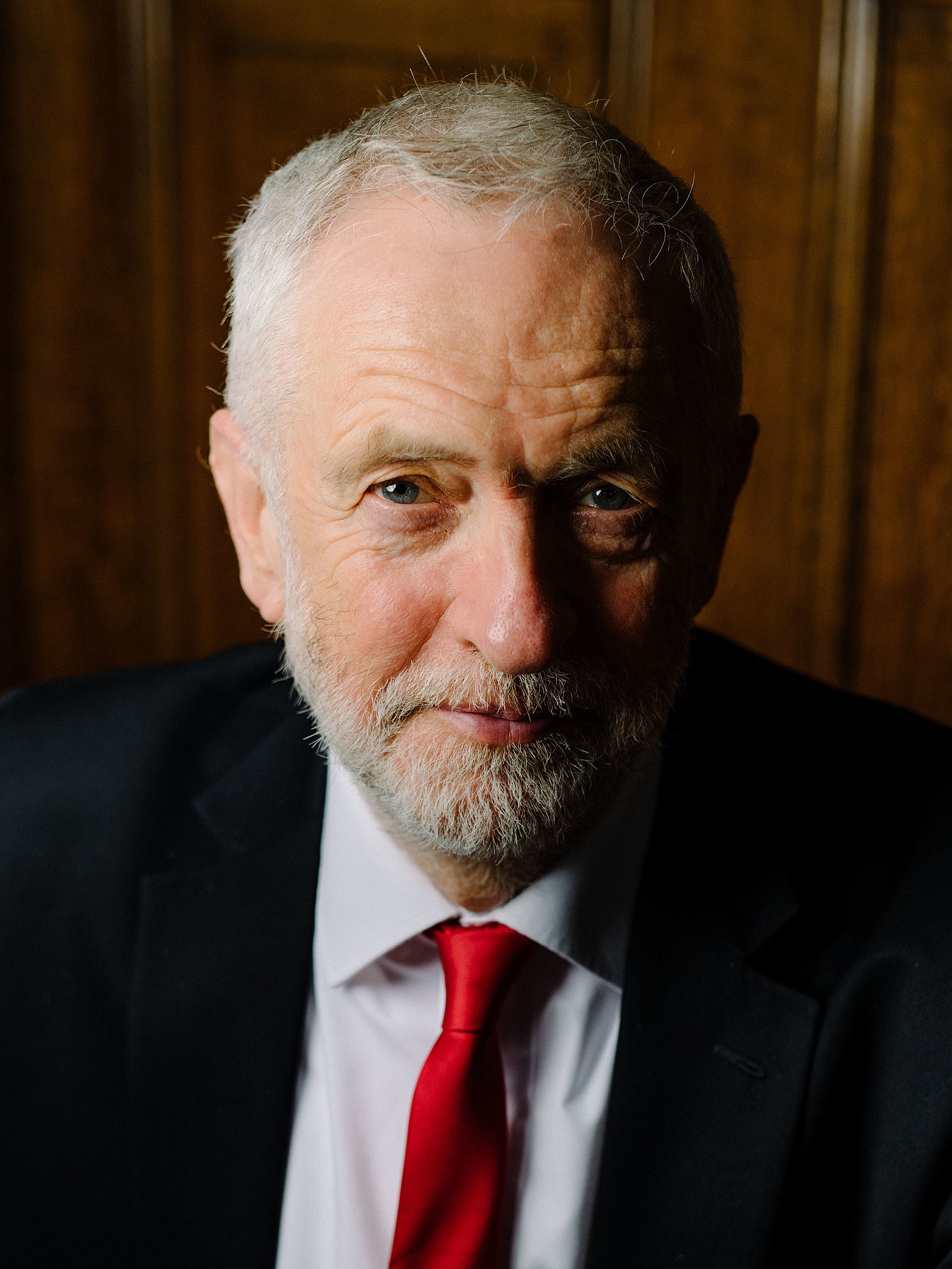

The Unquiet Country: Jeremy Corbyn, Zarah Sultana and the Bid to Build a Party for Unequal Britain

LONDON — On the afternoon of 24 July 2025, a bare-bones website suddenly lit up with traffic. Its message was stark: “It’s time to build a new kind of political party — one that belongs to you.” Below the slogan sat nothing more than a simple email sign-up box and the promise of a founding conference in the autumn.

Within hours, Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana — two MPs cast out of Keir Starmer’s Labour — had echoed the call across their social media feeds. The URL was plain, yourparty.uk. The name, Sultana quickly stressed, was only provisional. But the intent was not provisional at all: it was the unveiling of a new force, pitched at those who feel that modern Britain no longer works for them.

What followed startled Westminster. Corbyn claimed more than 80,000 sign-ups in the first five hours; allied accounts touted figures in the hundreds of thousands within days. Pollsters moved quickly: an Ipsos survey in late August reported that one in five Britons would consider voting for the project — rising to one in three among 16–34-year-olds, and strong among 2024 Labour and Green voters. Consideration is not conversion; still, it was a number impossible to ignore.

Behind the scenes, the effort took on legal shape. YOUR PARTY UK LTD was incorporated as a company limited by guarantee on 31 July 2025, with Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana listed among its directors. In British politics, such corporate scaffolding often precedes formal registration with the Electoral Commission. For critics, it was a vanity vehicle. For admirers, it looked like momentum.

The new party arrives into a country that has been quietly, stubbornly coming apart. Median household incomes are barely above pre-pandemic levels; the Gini coefficient for disposable income sits around 33%; poverty remains entrenched at roughly one in five people. The Resolution Foundation warns of a “lost half-decade” for living standards, with the poorer half expected to be worse off in 2029-30 than in 2019-20. Food insecurity in January 2025 was still twice its 2021 level. To live on a low income in Britain today is to devote over half your after-housing budget to essentials. These are not abstract figures; they are a description of daily life.

If there is a single story that explains why Corbyn and Sultana think there is space for a new party, it is stagnation. Real wages and productivity have barely moved for a decade and a half, the worst performance in generations. The IFS calculates that working-age incomes rose by a paltry 6% from 2007 to 2019, with little improvement since. Oxford Review of Economic Policy calls it what it is: a long freeze in pay combined with weak productivity growth. The British economic engine, once the pride of New Labour’s technocracy, has been idling.

Corbyn reads these charts as a moral indictment; Sultana, born in 1993, as a generational betrayal. Their opening platform points — public ownership of energy, water, rail and post; reinvestment in social housing; a harder line on inequality; an end to UK arms sales to Israel; and protections for protest — are pitched as a return to first principles in a political economy that has drifted. Supporters see in them a clean break from triangulation; detractors see warmed-over Corbynism.

The Party That Left the Working Class — or the Working Class That Left the Party?

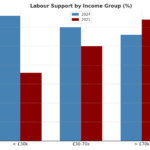

The phrase echoes through British life: Labour is no longer the party of the working class. The reality is more complicated — and more damning. The British Social Attitudes survey and post-election analyses show that age and education now sort voters more powerfully than class identity. In 2024, Labour won a sweeping majority on a modest vote share, regaining swathes of the “red wall,” while Reform UK surged to ~15% of the vote and five MPs — an historic performance for a challenger party. Beneath the headline numbers sat a stark pattern: non-graduates, older voters, Leave voters and lower-income homeowners drifted rightward, often to Reform; younger, degree-educated city dwellers coalesced around Labour and the Greens. The old loyalties have been replaced by culture and credential.

In parts of the white working class, that drift has a name: Nigel Farage. After winning Clacton in July 2024, Farage converted a protest brand into representation, drawing heavily from 2019 Conservatives and Brexit voters. Whether this is an ideological realignment or a howl of frustration matters less than its consequence: people who once saw Labour as their natural home now park their vote with a party that tells a simpler story about borders, belonging and betrayal.

Corbyn and Sultana are betting that another story — of ownership, services, and dignity — can peel off a different slice of the same electorate while mobilising millions who rarely vote. Their allies talk of Holyrood 2026 and the Senedd as the first proving grounds, where proportional systems reward broad sentiment rather than geographic concentration. Their critics ask a blunter question: under first-past-the-post, is any of this more than performance? Even Diane Abbott, a political ally of decades, went public in August to warn Corbyn against launching a party destined to be punished by the voting system.

The Long Shadow of New Labour

To understand the grievance animating this project, it helps to go back to Tony Blair. The Third Way modernised Labour and won landslides, but it also reimagined the party’s core constituency as a “new middle class” — aspirational, credentialed, at ease with market mechanisms. For years, growth and cheap credit papered over the losses; after 2008, the bargain frayed. Today’s research consensus is that Britain’s wage and productivity performance since the crash is the worst in two centuries, and that the distributional gains have been thin. The language of “what works” became a kind of managerial catechism even as fewer things worked.

Corbyn’s old leadership — and Sultana’s early career — were uprisings against that world. Their new party is the sequel: a bid to build an electoral home that doesn’t cede the terrain of ownership and inequality to think-tanks and comment pages. Ipsos’s findings — 20% consideration, strongest among the young and among 2024 Labour and Green voters — suggest an appetite for a left-of-Labour voice. The question is whether appetite yields votes, and votes yield seats. Under Britain’s rules, moral majorities do not automatically translate into parliamentary ones.

Movement vs. Machine

Spend time with Corbyn’s circle and you hear a mantra: “grassroots first.” The new party’s promise of an open founding conference, member-led policy and devolved organisation draws on years of movement practice — from local tenant campaigns to climate mobilisations. It also contains a contradiction. Company filings and news reporting point to familiar anxieties about branding, leadership and control: is this to be a loose federation of chapters, or a disciplined electoral machine? Will there be a single leader chosen at conference, or the co-leadership Sultana has floated? The answers will decide whether the party can scale beyond rallies and mailing lists.

There is another complication: the rest of the non-Labour left. On 2 September, the Green Party elected Zack Polanski its leader. His message was unambiguous — no pacts with Labour, open warfare with Reform, and an ambition to replace Labour in parts of England. For Corbyn and Sultana, who will fish in overlapping waters of young renters, graduates and public-sector workers, this is both opportunity and threat. The UK’s progressive vote is more crowded than it looks on paper.

Unequal Britain, Uncomfortable Choices

The strongest case for a Corbyn–Sultana party is not ideological purity; it is material reality. Poverty hovers around 21%; child poverty touches three in ten; the poorest households’ real incomes fell hardest during the cost-of-living crisis and are on track to lag for the rest of the decade. Even as headline inflation cools, rents and essentials take a growing share of low-income budgets. The IFS’s long graphs of income growth since 2009–10 read like a cardiogram gone flat.

The weakest case is arithmetic. Under first-past-the-post, diffuse enthusiasm delivers few seats. Reform UK won ~14–15% of votes in 2024 and came away with five MPs; the Liberal Democrats, more efficiently spread and locally organised, translated 12.6% into 72 seats. To break through, Corbyn and Sultana must do three hard things at once: geographically concentrate support, build a ward-by-ward machine, and avoid cannibalising the left in ways that hand marginal seats to their opponents. That is laborious work, not the stuff of viral clips.

The Labour government, for its part, has struggled to cast itself as the antidote to this malaise. Employment is softening; real incomes are sluggish; fiscal rules hem in ambition. The promise to be the party of “working people” collides with a macro-picture that feels stubbornly indifferent to who holds the red box. In this vacuum, Farage thrives on friction; the Greens sell coherence; and now Corbyn and Sultana offer a home for those who think the problem is the system itself.

The Hallam Question

Hovering at the edges is a figure some in the new party quietly wish would disappear: Roger Hallam, a co-founder of Extinction Rebellion and a strategist behind Just Stop Oil, who left prison in August after his sentence for conspiring to disrupt the M25 was reduced on appeal. Hallam has written an 86-page manifesto urging Corbyn and Sultana to build a party through relational organising: hundreds of small-group meetings, door-knocks that are conversations before they are canvasses, an explicit culture of respect. It is the method that helped XR explode into 400 local groups in a year. It is also political nitroglycerin: any public embrace risks the caricature that Your Party = JSO with ballots.

The movement left understands both truths: the method works; the messenger is a liability. Expect Corbyn and Sultana to borrow the former and politely ignore the latter.

A Country That Knows Its Own Story

Every British election is a referendum on what went wrong and who is to blame. For three decades, New Labour told a story about aspiration that resonated until the bills came due. The Conservatives offered sovereignty and fiscal virtue and delivered austerity and drift. Labour under Starmer offers stability — a virtue in a chaotic world, but brittle when rents rise, queues lengthen, and pay packets thin.

Corbyn and Sultana are trying to tell a different story: that ownership, services and a fair distribution of power are not antiquated slogans but the minimum conditions for a country that works. Their critics will say they are rearranging slogans while the voting system burns prospects to ash; their supporters will say you cannot fix a political economy without first changing what people imagine is possible.

The honest reading is that both might be true. Britain is unequal by design and by accident, and it will take more than managerial tweaks to change that. At the same time, first-past-the-post is indifferent to moral claims. It rewards patient, granular politics: councillors recruited; safe seats made unsafe; regional lists exploited where they exist; a thousand rooms in which politics begins with a chat rather than a speech.

If the new party is serious, that is what it will do. Amid the data points — the 20% consideration rate, the slow-bleeding wage graphs, the poverty charts — lies a blunt, unfashionable lesson: in Britain, movements do not become parties simply by willing it. They become parties when they live where inequality is a habit: at the food bank; in the private-rented flat with the damp; in the day-centre when the agency cancels a shift; on a bus route that no longer runs after dark.

Whether that becomes The Left, Your Party, or some other name to be settled by conference, the test is the same. In the coming months, watch Scotland and Wales, where proportional systems give insurgents their best odds. Watch the Greens, newly sharpened under Zack Polanski, for signs of cooperation or collision. And watch Labour: if it continues to speak the language of stability while presiding over stagnation, the vacuum will not remain empty. Someone will fill it. Corbyn and Sultana are wagering that, this time, it might be them.

1 Response

[…] The Unquiet Country: Jeremy Corbyn, Zarah Sultana and the Bid to Build a Party for Unequal Britain Examines how a new left-of-Labour formation aims to channel discontent over inequality, stagnating real incomes, and political alienation. […]