Britain’s Rentier Economy Is Why a Coffee Now Costs £5

The rise of the £5 coffee is not about wages or beans. It is about how Britain chose to organise its economy, and who it chose to reward.

I am sitting in Fitzrovia, just off Marylebone High Street, in a small independent cafe. It is the sort of place you barely notice at first: narrow room, a few tables, the quiet background noise of cups and conversation. I order a coffee, a latte. It costs £4. When I ask, almost as an aside, I am told it will soon be £5. I have already seen the story. The BBC reports that coffee prices across London, and much of Britain, are heading in that direction. Five pounds for a latte is no longer an exaggeration. It is becoming normal.

At first, it feels like another small irritation. Then a more serious question intrudes. What, exactly, am I paying for?

The answer matters because this is not really about coffee. Just as younger Londoners have been priced out of housing by rents that race ahead of wages, they are now being asked to normalise five pounds for a basic drink. The mechanism is the same. A growing share of the price is not paying for what is produced. It is paying for access.

This is the defining feature of a rentier economy.

A rentier economy is one in which income increasingly comes not from making things or providing services, but from owning scarce assets and charging others to use them. The core assets are land, housing, commercial property, and financial claims tied to them.

The main beneficiaries are a small minority:

- Residential landlords

- Commercial property owners

- Owners of land in constrained urban areas

- Financial institutions whose profits depend on rising asset values

They do not make the coffee. They do not build more housing. They do not improve productivity. They earn more because access to what they own has been made scarce, and scarcity allows rent extraction.

The coffee itself has not suddenly become rare. Beans are traded globally. Machines are standardised. Milk, water, electricity and labour have not risen in cost in line with the retail price. Yet the price keeps climbing.

So break it down.

The drink is cheaper in Vietnam. That is not controversial.

London (central cafe): £4.00

Ho Chi Minh City: £1.50 to £1.85

The difference does not come from ingredients.

Britain: £0.45 to £0.55

Vietnam: £0.30 to £0.40

Inputs are broadly similar.

Once the drink is stripped back to essentials, the product is recognisable in both places. The price difference sits outside the cup.

It sits in labour, rent, tax and compliance. But the crucial point is why those costs behave the way they do.

Labour is expensive in London because living in London is expensive. Wages must be high enough to cover the cost of housing. Rent has been driven up by land scarcity, planning constraints, credit expansion and the use of property as a wealth store. Higher rents push wages up. Higher wages push prices up. The price rise is then blamed on labour, even though much of the money flows straight through to landlords and asset owners.

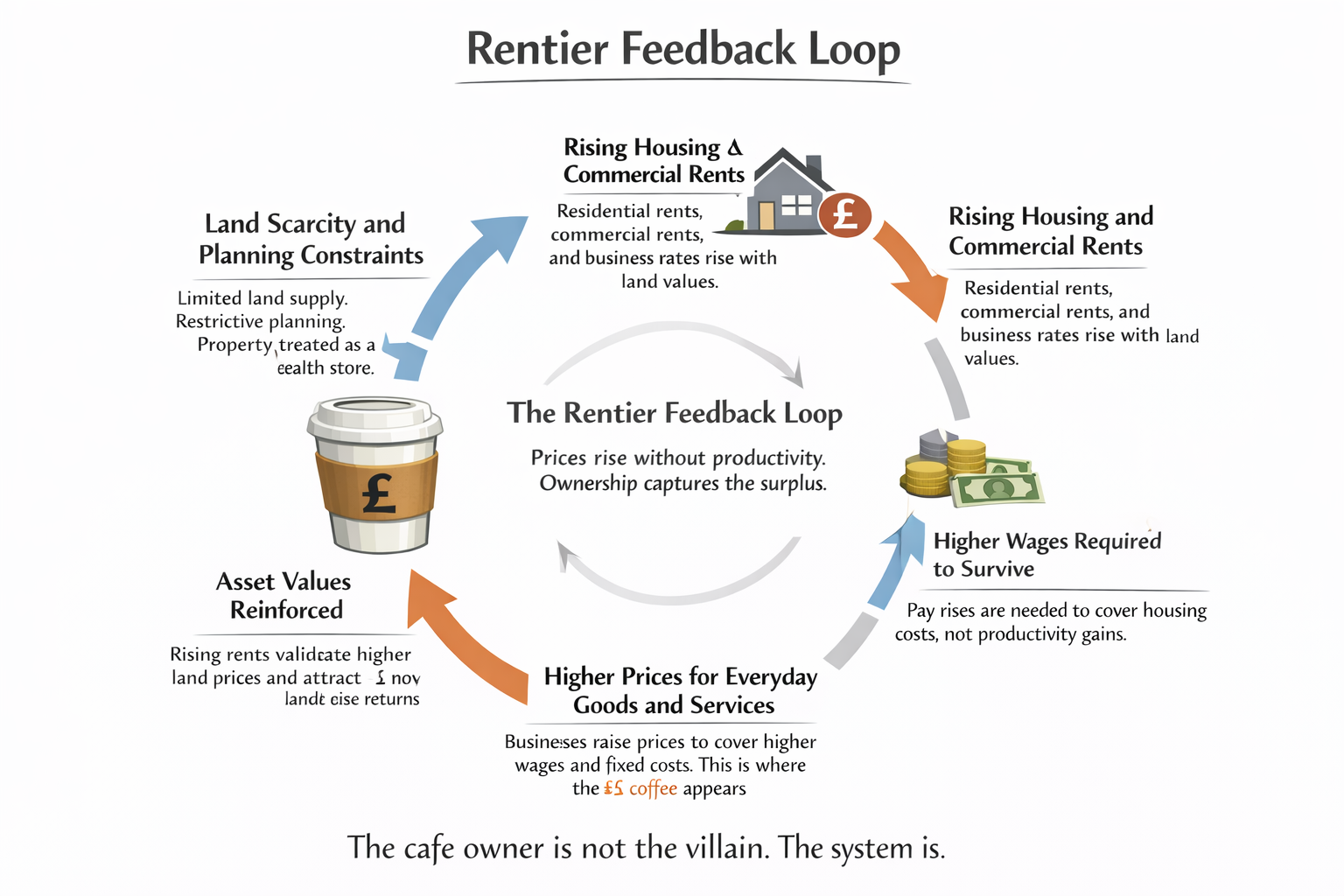

This is the rentier feedback loop in miniature.

Rentier feedback loop in Britain’s everyday service economy. The £5 coffee appears as an outcome, not a cause.

Britain: £0.20 to £0.40

Vietnam: £0.30 to £0.60

Despite lower prices, Vietnamese owners often retain more stable margins because the surrounding system does not extract the surplus first.

So where does the difference go?

Labour, rent, tax and compliance account for most of the difference.

Vietnam is not a romantic comparison. It is a controlled test. But a predictable objection follows: Vietnam is poorer.

So introduce a control case that removes poverty from the explanation.

Germany is a rich, high wage, industrial economy using the same machines, beans and supply chains. If high wages alone explained British prices, Germany should look similar.

It does not.

London: £4.00

Berlin or Munich: £2.20 to £2.80

The difference is structural, not moral.

Germany constrains land and housing differently. Rents are anchored by the Mietspiegel, a transparent local rent index that limits speculative escalation. Long tenancies are normal and secure. Its decentralised banking system channels credit toward local industry and productive investment rather than urban land speculation. Commercial rents absorb a smaller share of turnover, and asset inflation is not treated as a national growth strategy.

As a result, everyday services remain cheaper in a rich economy.

Britain, by contrast, prices ordinary life as access to a financialised system.

That system has a name.

An economy where income and price formation are driven primarily by ownership of scarce assets rather than productive activity. Returns flow to those who own and restrict access, not those who produce.

In England, the beneficiaries are concentrated and skew older. Younger cohorts pay rent. Older cohorts receive it. Wealth accumulates through ownership, not work. The gap widens across generations.

This system raises the cost of:

- Housing

- Commercial rents

- Business rates

- Everyday services

- Labour-intensive goods

The £5 latte is not really about coffee. It is a toll charged by a system that prices access rather than production.

Rentier economies appear stable. They are not productive. Growth slows. Investment flows into existing assets instead of new capacity. Prices rise faster than living standards.

This is not fate. It is policy.

Britain chose to financialise housing, protect land scarcity, favour asset appreciation and tax transactions instead of rents. Germany chose differently.

Nothing about the current outcome is inevitable. But nothing about it will correct itself either.

The question is not whether Britain can afford a five pound latte. It can.

The question is what kind of economy produces one, and who it is really for.

A rentier economy is not complicated. It is an economy where income flows to those who control access, not to those who produce. A relatively small section of society owns scarce assets and lives off the rents those assets generate. They do not make the coffee. They do not build more homes. They do not expand capacity or raise productivity. They own land, property, infrastructure, legal privileges, and financial claims, often held and transmitted through trusts and inheritance vehicles that preserve scarcity across generations.

This group benefits precisely because scarcity is maintained. Planning restrictions, credit allocation, tax design, regulatory barriers, and monopoly protections all work to limit supply and protect asset values. As scarcity deepens, rents rise. As rents rise, labour costs rise just to survive. Prices then rise to cover labour. The cycle feeds itself. Meanwhile, much of this rentier income is lightly taxed compared with work, consumption, and small business activity. Effort carries the burden. Ownership collects the return.

The consequences are visible everywhere. Businesses work harder and keep less. Younger generations produce more and own less. Productivity stagnates while asset values surge. The economy looks busy, yet value drains upward through every transaction. That is why growth feels hollow, why living standards erode despite employment, and why a basic coffee drifts from four pounds to five, untethered from what is actually in the cup.

The £5 latte is not an anomaly. It is evidence. When too much of economic life is priced as access rather than output, everyday activity becomes a toll road. That is what a rentier economy looks like when it reaches the street.

This diagnosis follows a growing body of work on rentier capitalism, including the analysis of Guy Standing and Brett Christophers, who have documented how asset ownership increasingly dominates income, prices, and economic power in advanced economies.

Britain’s Productivity Collapse and the Rentier Trap

Britain’s economy is not broken. It is being quietly mismanaged

HS2 as Mirror: How Britain Lost the Ability to Build, Govern, and Deliver

The Rent Crisis Was Manufactured — To Serve Profit, Not Shelter

Britain’s new migration model: fewer brains, more bills

Why Britain turned a Chinese embassy into a national security crisis

Britain has chosen big pharma over the NHS